The following quaint little tale of days gone by was related by a Silesian physician named Mortinus Weinrichius, apparently an eyewitness to the whole proceedings. It was published by Henry Moore in his 1653 book “An Antidote Against Atheism.”

The star of our show was a resident of the Silesian town of Pertsch named Johannes Cuntze. (Some sources give his name as “Cuntius,” which is no improvement.) Cuntze was around sixty years old. He was an alderman, quite prosperous, “very fair in his carriage,” and was generally regarded as one of Pertsch’s most respectable citizens.

One day early in February 1592, the mayor summoned Cuntze to his home to help deal with some vexing local business matters. (Cuntze was “a very understanding man, and dexterous at the dispatch of business.”) After the issue was resolved to everyone’s satisfaction, the mayor invited Cuntze to stay for supper. Cuntze asked to be allowed to go to his home first to deal with some personal affairs. As he left, Cuntze said cheerily, “It’s good to be merry while we may, for mischiefs grow up fast enough daily.”

As we shall see, Cuntze didn’t know the half of it.

Cuntze ordered one of his “lusty geldings” to be brought out of his stable. As one of the horse’s shoes was loose, Cuntze and one of his servants immediately began repairing it. Unfortunately, the horse, “being mad and mettlesome,” struck Cuntze’s head with a massive kick. When Cuntze regained consciousness, he cried out “Woe is me, how do I burn and am all on a fire!”

Cuntze kept repeating these despairing words. He then began raving about how “his sins were such that they were utterly unpardonable.” He refused to say what those sins were, and rejected suggestions that a member of the clergy be summoned.

Cuntze’s neighbors had long wondered how he had acquired his wealth. His strange behavior now spawned rumors that he had sold his soul to the Devil.

One night soon after his injury, Cuntze’s eldest son was sitting by his father’s bedside. He saw a black cat claw open the casement, run to the bed, and violently scratch the stricken man’s face. Then, it suddenly disappeared. At that moment, Cuntze died.

As soon as Cuntze passed away, a violent storm of wind and snow arose, reaching its peak during Cuntze’s funeral. The moment he was interred, the tempest ceased.

Unsurprisingly, all these sinister events confirmed the worst suspicions about Cuntze. Stories began to spread that although the alderman may have been buried, he was hardly resting in peace. It was said that a “Spiritus Incubus” in Cuntze’s form tried to rape a woman. Soon afterwards, the same “Incubus” appeared in a room where someone was sleeping. The spectre awakened the man, announcing in Cuntze’s voice, “I can scarce withhold myself from beating thee to death!”

The town watchmen reported that every night, they heard “great stirs” from Cuntze’s house, “the falling and throwing of things about; and that they did see the gates stand wide open betimes in the morning, though they were never so diligently shut o’re night; that his horses were very unquiet in the stable, as if they kicked and bit one another; besides unusual barkings and howlings of dogs, all over the town.”

Death clearly did not become Cuntze.

One night, the servants of one of Pertsch’s citizens heard the sounds of loud trampling throughout the house. The residence began shaking as if it might collapse, and the windows were filled with flashes of light. In the morning, the master of the household found outside his home strange footprints in the snow, “such as were like neither horses, nor cows, nor hogs, nor any creature that he knew.”

On another night, Cuntze’s spirit appeared to a friend of his, saying he had a matter of great importance to communicate. “I have left behind me,” Cuntze said, “my youngest son James, to whom you are god-father. Now there is at my eldest son Steven’s, a citizen of Iegerdorf, a certain chest wherein I have put four hundred florins: This I tell you, that your god-son may not be defrauded of any of them, and it is your duty to look after it, which, if you neglect, woe be to you.” The ghost then departed for the upper rooms of the house, “where he walked so stoutly, that all rattled again, and the roof swagged with his heavy stampings.”

Since his death, Cuntze’s widow had shared their bed with a maidservant. His ghost took to appearing at the bedside, ordering the maid out so he could retake his rightful place in the bed, threatening to “writhe her neck behind her" if she did not comply. His ghost could be seen riding through the streets of Pertsch and the surrounding countryside, “with so strong a trot, that he made the very ground flash with fire under him.” The wraith took to attacking, and even killing, random townspeople. On one occasion, he came through the casement of his home “in the shape of a little dwarf.” He attacked his wife so viciously that he would have torn her throat out if her daughters hadn’t come to the rescue. His household was so terrorized by the ghost that the servants all slept together in the same room, watching for the approach of the “troublesome fiend.” One night, a maid, braver--or perhaps more foolhardy--than the rest, insisted on sleeping alone. Cuntze appeared in her room, where he pulled off her bedding and would have carried her off with him if she hadn’t managed to break free and run back to the others. Cuntze filled the house of a local divine with such a “grievous stink” that the theologer became terribly ill, as if he had been poisoned. Not even the local animals were safe. The wraith would snatch up dogs in the streets and knock their brains against the ground. He sucked the cows dry of milk. He flung goats and poultry around their barns. It was also noted that Cuntze’s gravestone was turned to one side, and that there were several holes in the earth that went down to his coffin. No matter how many times the holes were filled in, they would return overnight.

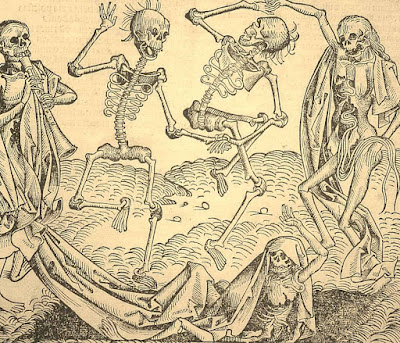

Many more of the ghost’s evil deeds were recorded, but you get the idea: The late Mr. Cuntze was making a thorough pest of himself. The citizens of Pertsch concluded they had a vampire in their midst.

Before long, Pertsch nearly became extinct. As nobody would lodge in the town, trade came to a halt, leaving most of the citizens facing bankruptcy. Clearly, something had to be done about their resident ghoul. About five months after Cuntze died, his body was exhumed. The townspeople found that the corpse showed no sign of decay. When a vein was opened in one leg, fresh blood sprang out.

You will be gratified to learn that in 16th century Silesia, even vampires were treated fairly under the law. A committee of judges, having heard all the details of this case, pronounced Cuntze guilty of being a posthumous danger to society, and ruled that his corpse must be burned.

And so it was done. Once the body had turned to a mere pile of ashes, they were carefully swept up and thrown into the nearest river. And the disagreeable spirit of Johannes Cuntze was never seen again.

I'm surprised it took the citizens five months to do something about Cuntze's corpse. He seemed to worry about his son, James, though.

ReplyDeleteWhich worry surprised me. Last thing I would have thought of him.

ReplyDelete