"...we should pass over all biographies of 'the good and the great,' while we search carefully the slight records of wretches who died in prison, in Bedlam, or upon the gallows."

~Edgar Allan Poe

Friday, June 28, 2019

Weekend Link Dump

This week's Link Dump features yet another of our Cats From the Past!

Meet Sam. As has always been the case with me, Fate brought him into my household. When I first made Sam's acquaintance, he was a neighborhood stray. Apparently, his owners had moved away, leaving him behind. (Yes, I know. Special place in Hell.) An elderly man who lived across the street from us fed Sam and generally took responsibility for him, but he remained an outdoors cat. (It was also this man who named the cat "Sam," because, as he once told me, at first he didn't know if the cat was a "Sam" or "Samantha.") Sam and I became great friends, and he took to hanging out in our yard.

Things went on like this for a few years, until our elderly neighbor died. You might say we "inherited" Sam. Life went on, until one memorable day when Sam decided it would be a fine idea to attack a very large neighborhood dog. (The dog got by far the worst of the fight.) This led us to decide we had to bring Sam inside, although since he had been an outdoor cat all his life, we weren't sure how he'd adjust. Fortunately, he loved being an indoor guy. He particularly loved sleeping on beds. And when he realized that at night, a human would join him there, his joy was unbounded.

Sadly, Sam was not part of our household for very long. We had no idea how old he was, but we knew that he must have been of an advanced age. After he had been indoors only about two years, he developed some incurable health issues, and passed away.

Sammy wouldn't have won too many beauty contests, and I fear he would have fared little better with an IQ test, but he was a cheerful, outgoing, good-natured lunkhead of a guy. To know him was to love him.

Unless you were a dog, of course.

What the hell happened at Dyatlov Pass?

Watch out for the Werewolf of Chalons!

Some tips for the next time you interview a serial killer.

Raven romance in the Tower of London.

The story behind the "rule of thumb."

An execution linked to the notorious murder of Lord Darnley.

I have to say, if you're name is "Zack MacLeod Pinsent," you have no choice but to dress like a Regency dude.

A mysterious assault leads to suicide.

Was there a serial killer roaming early 20th century America?

Breakfast with the Duchess of Devonshire.

You might like to know that New York's Central Park is full of people running around counting squirrels.

A puzzling poisoning in Antarctica.

A puzzling disappearance in Australia.

The alleged disappearance of a Chinese village.

This week in Russian Weird looks at the Siberian Atlantis. And the Perm Anomalous Zone.

A brief history of air conditioners.

Censoring Tennessee Williams.

Archaeologists have found the elixir of immortality.

The legend of the Bride From the Underworld.

The Victorian Harry Potter.

How to exercise in outer space.

The making of the Treaty of Versailles.

The Great Catnip Caper.

Fashionable widow's rings.

Latvia's "Valley of Spirits."

The Montgomery Murders.

Thomas Jefferson and Maria Cosway.

A tragedy in Butler County.

Albania's Virgin Matriarchs.

And so we come to the end of the line for yet another Link Dump. See you on Monday, when we'll meet the Avon Lady From Hell. In the meantime, here's some Nilsson:

Wednesday, June 26, 2019

Newspaper Clipping of the Day

|

| Via Newspapers.com |

Let's recap: to date, I have brought you ghost cats, talking cats, goblin cats, hoodoo cats, and hypnotist cats. What's the one thing missing?

Why, of course. Martini-swilling cats. The "Oshkosh Northwestern," July 22, 1949:

Kiki, an old foreign toper, came to the land of plenty today--and promptly went on the wagon.

Kiki, to be real plain about it, couldn't stomach our martinis. Not sweet enough.

Kiki, who was raised on gin and vermouth, is a cat. A fugitive from the back alley of old Madrid; a gray and white rascal of doubtful parentage and the property of Mrs. Winifred Hunter, a 62-year-old widow who has just returned from an official tour of duty in Spain. Mrs. H. as of now is waiting for a reassignment, after 26 years of foreign service with our government.

When she walked into the Hunter-Kiki hotel room for a chat, the lovely Mrs. Hunter, who looks half her age, said "Be careful." This reporter disregarded the warning and has a couple of Kiki's toothmarks on his left arm to prove it.

Mrs. Hunter, after she bandaged the damage, explained that (1) Kiki doesn't like men; (2) he is no sissy.

There was no argument on either count.

Before she told me about the drinking habits of her pet, Mrs. Hunter admitted there had been trouble before over Kiki, who came to this country billed as a martini-drinking, boxing tabby."

"I taught him to box," she said. "He was raised around children and so I made him some boxing gloves so he wouldn't scratch the little ones."

Well, when Mrs. Hunter and Kiki landed in New York in the middle of July the cat demonstrated both of his talents. Ship reporters wanted pictures for the papers. Kiki was accommodating enough to lap up a martini--a sweet one like he was accustomed to in Spain. But he got a little unhappy with a reporter from the New York Herald Tribune who got a little too folksy.

"One of Kiki's gloves had blown overboard, but I had one on his left paw for safety," said Mrs. Hunter. "Kiki is right pawed and he could have been mean about it. But he is a gentleman. He let the man have a good one with his left, or gloved hand. The man did not appreciate it."

If Kiki says anything at all, except "meow," he says it in Spanish, since he understands very little, if any, English.

Kiki makes a catline for under the bed when Mrs. Hunter says "malo malo." That means "bad bad." Or to a cat "spanky, spanky."

"Quieta," spoken to the pussy means about what it says. Quiet! "Tamo" means "take it" or "eat your supper."

Kiki knows.

But back to the martinis and how Kiki developed the habit.

Mrs. Hunter pitched a cocktail party in Madrid soon after she got her alley cat as a gift from a Spanish princess. A gentleman guest came rushing into the room and said that Kiki was stealing his martinis.

"I had trouble with the cat ever after," she said.

On the way over here, Kiki made sort of a nuisance of himself running up and down the bar, lapping up the dregs.

He's cured now, though. These American martinis are too tough. Almost cured, that is.

While I was talking to Mrs. H., somebody stole my olive.

|

| "New York Daily News," July 12, 1949 |

I think I must have been Kiki in a former life.

Monday, June 24, 2019

The Ghost of Anne Walker; Or, Dead Women Do Tell Tales

|

| "Illustrated Police News," 1881, via Newspapers.com |

I dare say that being murdered is never pleasing, under any circumstances. Imagine how much more irritating it is for the victim when there are no indications that your death will ever be avenged, leaving your murderer to walk free.

What is a ghost to do, except take the matter into its own hands and turn spectral detective?

About the year 1631, a widower, a "yeoman of good estate" named John Walker lived in the English village of Great Lumley. His live-in housekeeper was a niece, Anne Walker, an attractive young woman in her twenties. We do not know much else about John, other than that he was unpopular among his neighbors. He apparently was one of those people who, for undefinable reasons, had a knack for inspiring dislike and distrust. So it was small wonder that when Anne suddenly disappeared from Great Lumley, villagers immediately suspected some very unpleasant things. According to John, his niece had taken ill, and went to stay with an aunt in a neighboring village until she recuperated. However, the common belief was that John sent the girl away because he had gotten her pregnant.

Anne Walker's fate seemed destined to remain a mystery. Then, a Great Lumley miller named James Graham began having some very unsettling experiences. One night, he was working alone in his mill, when he saw the figure of a young woman approach him. She was of disheveled appearance, and had five ghastly wounds on her head. The "affrighted and amaz'd" Graham, realizing he was seeing a particularly horrifying ghost, quickly crossed himself. The spirit told him, "I am the spirit of Anne Walker, who while in the flesh, lived with your neighbor John Walker; I was betrayed by Walker."

The wraith went on to say that after she became pregnant, John sent her to to stay with her aunt. Soon before she was to give birth, Walker paid one Mark Sharpe to take her away from her aunt's home, claiming that he would bring her to some more suitable place to await her confinement. Instead, Sharpe brought her to a lonely moor, where he used "a pick, such as men dig coal withal, and gave me these five wounds." Her body was then dumped in a coal pit. She ordered Graham to relate her story to the nearest justice of the peace, warning him that until he did, she would continue to haunt him.

Graham, who was described as "a practical, no nonsense man, who would not court even an ignorant fear of the supernatural,"could not bring himself to follow these instructions. He feared, not unreasonably, that everyone would think he had lost his mind. But the murdered woman was not going to be put off so easily. She made a second appearance, and in a "stern and vindictive" manner demanded that Graham obey her wishes. When that also failed to move Graham, the now "very fierce and cruel" ghost returned a third time.

Graham finally got the message. He did not want to see what she would do on a fourth visit. The miller went to the magistrate and repeated what Anne's ghost had told him. Fortunately for Graham, his reputation for honesty and probity was such that his bizarre tale was taken seriously. A search was made of the area, which resulted in the discovery of the poor woman's corpse. She was found in the exact location described by the ghost, and the wounds on the body were identical to those Graham had seen on the wraith. The apparition had also helpfully provided the spot where the murder weapon and Mark Sharpe's bloody clothes had been hidden.

Sharpe and John Walker were promptly arrested and put on trial for murder. Unsurprisingly, the case created "an immense sensation." Further paranormal evidence was provided by the jury foreman, a Mr. Fairhair. Fairhair testified under oath that during the trial, he witnessed "the likeness of a child, stand upon Walker's shoulders." It was even reported that at the conclusion of the trial, Anne made an appearance in the courtroom, holding a baby in her arms and chanting, "Hush a baby! hush a baby! hush a baby be! 'Twas Sharpe and Walker that killed thou and me!" According to rumor, Anne's terrible spirit visited the judge as well. As far as everyone was concerned, all this was definitive proof that Walker had indeed made his niece pregnant, which led him to hire Sharpe to murder her. Despite the fact that neither man ever confessed to the foul deed, they were both found guilty and hanged.

Anne Walker's revenge was now complete, and her ghost was seen no more.

Friday, June 21, 2019

Weekend Link Dump

This week's Link Dump is hosted by a celebrity: Puzzums, one of the biggest feline film stars of the 1920s. (Shown with his owner, Nadine Dennis, who ironically had a much less successful acting career.)

What the hell happened to Dennis Martin?

What the hell happened to the lighthouse keepers of Eilean Mor?

What the hell happened to the children of Hamelin?

Watch out for those haunted railroad tracks!

Alice Ramsey set out to become the first woman to drive across the U.S.

Mayhem in Victorian music halls.

How to drink like an ancient Celt.

How to float a giant sphinx.

This week in Weird Archaeology visits a mysterious carved face in India.

This week in Russian Weird visits the Black Bird of Chernobyl.

What we know--and still don't know--about MH370.

Behold, an early 20th century Korean sitcom.

A Christmas UFO at Bury St. Edmunds.

If you can't book your local church for your wedding, how about the cemetery?

The world's greatest matchmaker is a tree.

A female blackjack player in the Old West.

America's first black radio station.

The travails of an 18th century family servant.

A look at the first Australians.

A swimming pool suicide pact.

Letters from doomed miners.

Alfred, the Comeback King.

Part two of the Cats of Carnegie Hill.

Neolithic artificial islands.

The Trojan War, fact and fiction.

The Lascars of the Marshalsea.

A 17th century female playwright.

The Nazi-era "Prince of Bibliophiles."

Victorian sunscreen.

A missionary and his dog.

No, a slave was not burned to death for witchcraft in 1779. He still came to a sticky end, though.

The life of Jane Austen's brother.

A woman's mysterious death.

Believe it or not, there are worse things than migraines.

Vegetable syrup, good for whatever ails you.

That's all for this week! See you on Monday, when we'll look at a ghost who avenged its own murder. In the meantime, here's a bit of Telemann:

Wednesday, June 19, 2019

Newspaper Clipping of the Day

|

| Via Newspapers.com |

All right, let's talk phantom cows. From the "Ellsworth Reporter," November 8, 1888:

A farmer named Burt B.. living in the bottoms between Kansas City Kansas, and Quindaro, tells of a peculiar annoyance which he has with what he claims is a phantom cow.

According to the story which he tells, and in which his family acquiesce, a large brindle cow of his dairy got into his basement one afternoon and ate a large number of watermelons which his boys, Frank and Archie, aged 11 and 13, had put on ice, intending to take them to town and sell them for spending money. They found the bovine after she had despoiled their hopes, and were so enraged that after cornering and tormenting her with a vindictiveness that only disappointed boys can contrive, they shot the cow.

Mr. B. caught them just then, and as she was a valuable animal, did all in his power to save her. But the wound was bad, and coupled with a severe colic which the over-indulgence in melons had caused, she died in the morning after a night of horrible agony, during which the most dreadful groans broke continually from her suffering system. Since that time, at irregular intervals, the inmates of the house are nearly driven to distraction by pitiful sepulchral moans which burst forth without warning and continue for hours. They pervade the house and render the place a perfect pandemonium. Two or three times he has gone to the cellar, avowing that a cow had gotten in there.

The worst of it is, however that the two boys rave when they hear the dread sounds, and insist that they see a cow in the room, and that she is trying to gore them. Again, they assert the bovine is jumping through the window, next in the corner then under the bed. When the boys are away from home there is no trouble, but as soon as they return the haunt commences. He is at a great loss as to the means by . which to conjure the "bossy spook" to rest.

Eh, those two vicious little brats get no sympathy from me.

Not to be outdone, the "New York World" for August 9, 1896 said, "We'll see your phantom cow and raise you one phantom headless cow:

A new kind of spook has appeared to frighten timid people in Cumbria County, Pa. A spectre cow, with her head severed from her body and dangling in the air in front of her, has appeared to several people who have chanced to pass near her haunts at night, and all unite in saying that the sight was most terrifying.

Elmer Person, city editor of Pennsylvania Grit, a newspaper published at Williamsport, has investigated the stories told by several people regarding the apparition and finds that they all agree in every particular. He interviewed a number of folks who claim to have seen the spook and he vouches for their respectability and declares that they believe the stories they tell.

As describe by the men seen by Mr. Person the ghost is a frightful object. At a late hour at night the spook is seen madly cavorting along the roadside, at times using the rail fences as a path, occasionally careening wildly along stone fences and again taking to the air. At all times the head of the cow appears severed from the body, looming fearsomely some feet in advance of the rear of the spectre.

The abode of the ghost is in a ruined building near Johnstown. the building was formerly used as a slaughter-house and innumerable cows lost their lives there. It has been untenanted for years and stands in an isolated and lonesome spot. Ever since the butcher abandoned the premises uncanny things have been told about it and children have been afraid to pass the spot at night.

Many people who have passed the place after sundown have seen the bovine spook. They say that the form of a cow suddenly dashes out of the rickety building, which stands some distance back from the road, and runs past them with the speed of an express train. The head maintains a uniform distance from the body and from the severed and bleeding neck come frightful cries that would chill the warmest blood.

The eyes flash fire as the cow passes the frightened spectator. The mouth is always open, and the teeth--large and jagged--are plainly seen and are apparently lighted with some sort of greenish fire. The bellowing is awful and can be heard for a long distance.

The spectre's always seen either leaving the old slaughter-house or else returning to it. One spectator who watched one night said that after emerging from the building the ghost went down the road, at times running on top of the stake-and-rider fence until the stone fence was encountered at the edge of what is known as Climber's Hill.

Then it followed the stone fence across the hill, and, after giving one tremendous bellow, retrace its steps. Arriving in front of the former shambles the spectre cow paused for a moment, and then, with a wild burst of noises more hideous than before, dashed into the building and disappeared.

Mr. Person puts forth the story as one worthy of all credence. He adds that the people for miles around are very much excited about the spook, and none is able to offer explanations that are satisfactory. No one who has encountered the spook once can be induce to go near the place again at night. One sight of the headless cow as she dashes down the road bellowing hoarsely through the stump of a neck is all that anyone cares to have.

The country about the scene of the terrifying occurrences is wild and hilly. There was formerly considerable travel along the road which led past the slaughter-house, but since the ghostly cow has begun traveling the thoroughfare at night with teeth that look like bicycle lanterns and with a hea that refuses to stay where it belongs, things have changed considerably and people drive around the other way.

"That headless cow spook seems funny in the daytime," said one man who saw it, "but at night there is nothing funny about her. I saw her once and heard her bellow, and I shall not go past that old slaughter-house again soon after dark."

Still in the mood for that steak?

Monday, June 17, 2019

Mabel de Belleme's Real-Life Game of Thrones

|

| Not our Mabel, but I'm sure she'd approve. |

Medieval women are often stereotyped as rather dull creatures: lacking power or influence, constrained by their narrow position in life. Pious, gentle, helpless pawns of their male-dominated world. Utterly harmless.

And then we turn to Mabel, Dame d'Alencon, de Seez, and de Belleme, Countess of Shrewsbury and Lady of Arundel. Most of what we know about her busy and zestful career comes from Orderic Vitalis, who wrote one of the major contemporary histories of 11th and 12th century Normandy and England. Although medieval chronicles can be erroneous, exaggerated, or downright untruthful, Orderic is considered by modern historians to be a generally reliable source. In any case, even if a fraction of what Orderic recorded about our heroine's life is correct, Mabel was a woman well worthy of inclusion in the hallowed pages of Strange Company.

Mabel was born in Normandy circa 1026 to William I Talvas, seigneur of Alencon and his first wife Hildeburg. Her parents' marriage set the tone for Mabel's life. According to Orderic, William came to despise his wife because "she loved God and would not support his wickedness," so he had her strangled as she was on her way to church.

|

| Victorian era illustration of 11th century Normans |

Mabel grew up as heiress to the estates of the mighty House of Belleme. She inherited further wealth when her uncle the Bishop of Seez died in 1070. However, all this land and power seemed to never be enough for our Mabel. Her career was marked by an insatiable greed for more properties, and she was not at all finicky about how she obtained them. Some time in the early 1050s she was married to Roger de Montgomery, who later became the first Earl of Shrewsbury.

Roger was a great favorite of Duke William of Normandy, who was soon to earn his famous nickname, "the Conqueror." When William made his history-changing invasion of England, Roger stayed in Normandy to serve as co-regent with William's wife Matilda. When he joined William in England in 1067, the new king rewarded him with an earldom and so many estates that Roger was one of the biggest landowners in the Domesday Book.

If Orderic is to be trusted, Mabel used all this wealth and influence to make a thorough menace of herself. Of all the prominent women mentioned in his chronicles, she stands out as by far the worst of the lot. He literally did not have a good word to say about her. Orderic characterized Mabel as "small, very talkative, ready enough to do evil, shrewd and jocular, extremely cruel and daring." Orderic emphasized Mabel's cunning, her ruthlessness, her rapacity, and her treachery. On top of all this, her son, Robert de Belleme, was an even more savage specimen, "unequaled for his iniquity in the whole Christian era."

For some years, Mabel's family had been at feud with a rival clan, the Giroies--a clash she was more than eager to escalate. Her main target was one Arnold de Echauffour. (Arnold's father, William fitz Giroie, had been mutilated and blinded by Mabel's father at a wedding celebration. Don't ask.) Mabel and Roger convinced then-Duke William to confiscate Arnold's lands and give the lion's share to them. However, in 1063, Arnold regained the Duke's favor, as well as a promise to have his lands restored.

Well. Mabel would have none of that. Obviously, she had no choice but to murder Arnold. When Arnold paid a visit to his Castle of Echauffour (at that time in Mabel's possession) she had him served poisoned wine. However--sensing what was in the wind--he declined to drink it. The wine was instead imbibed by Mabel's brother-in-law, who proved the efficacy of her poisons by dying three days later. (One wonders how Mabel broke the news to her husband. Awkward.) Undeterred, Mabel bribed Arnold's chamberlain to make another poisoning attempt. And Arnold de Echauffour was soon no more.

Although she had some regard for Theodoric, abbot of Saint-Evroul, Mabel had an unsurprising hatred for the clergy. She must have felt they really tried to cramp her style. She had a special dislike for Saint-Evroul, as it had been founded by the Giroie family. She obviously could not treat men of God in quite the same brutal fashion that she handled her political enemies, but she still found ways to make trouble for the monks. In 1064, Mabel deliberately put a huge financial burden on Saint-Evroul by making long visits to the abbey with a large entourage. When Theodoric dared to chide her for the "sinful absurdity of coming with such a splendid retinue to the dwelling of poor anchorites," she angrily retorted, "When I come again my followers shall be still more numerous!"

Theodoric warned Mabel that if she did not repent, "you will suffer what will be very painful to you." Well, that very evening, she did indeed suddenly fall painfully ill. She quickly left the abbey, never to return. (It is generally surmised that Mabel's punishment came less from the hand of God and more from the hand of a monk who slipped something nasty into her dinner.) It is said that in her flight, the ailing Mabel passed the cottage of a farmer whose wife had just given birth. She had the baby brought to her to be suckled, hoping that might relieve her pain. We are told that this unconventional treatment worked. By the time Mabel arrived home, she was in perfect health.

Of course, the infant soon died, but what of that?

Mabel was not one to let such minor setbacks get her down. She made herself feared and hated for her habit of plundering the lands of others. Many nobles, we are told, were reduced to destitution thanks to her antics.

In 1077, she made a fatal error when she seized the hereditary lands of one Hugh Bunel. On December 2, 1079, Bunel had his revenge. He and his three brothers snuck into the castle of Bures, where Mabel was then living. The men ambushed her as she was lying in bed, "having just enjoyed the pleasures of a bath," and lopped off her head with a sword. The killers then fled, successfully avoiding capture.

It's good to know Mabel didn't disappoint us by dying peacefully of natural causes.

Orderic closed his account of Mabel's lively career by quoting her epitaph:

Sprung from the noble and the brave,Orderic couldn't resist snorting that this eulogy was "due more to the partiality of her friends than her own merits."

Here Mabel finds a narrow grave.

But, above all woman’s glory,

Fills a page in famous story.

Commanding, eloquent, and wise,

And prompt to daring enterprise;

Though slight her form, her soul was great,

And, proudly swelling in her state,

Rich dress, and pomp, and retinue,

Lent it their grace and honours due.

The border’s guard, the country’s shield,

Both love and fear her might revealed,

Till Hugh, revengeful, gained her bower,

In dark December’s midnight hour.

Then saw the Dive’s o’erflowing stream

The ruthless murderer’s poignard gleam.

Now friends, some moments kindly spare,

For her soul’s rest to breathe a prayer!

Friday, June 14, 2019

Weekend Link Dump

This handsome cat displays an expression not uncommon among those who visit this blog for the first time.

Watch out for those haunted elevators!

Watch out for those haunted cars!

Watch out for those Swedish ghost pigs!

The Chevalier and his Clowder.

Why gin explains a lot about the 18th century.

Some bridesmaid superstitions.

The murder of a roadhouse keeper.

The barber and the abusive parrot.

The Green Vault.

If a member of Parliament asks you to burn down a ship, it's best to refuse.

Agatha Christie's real-life mystery.

"The Ruin of Britain." And considering this was written sometime in the 5th or 6th century, the title was not hyperbole.

The legend of King Lear and Cordelia.

Medieval medical schools.

A man put to death for having a conscience.

The house of haunted mannequins.

That particularly appalling poisoner Graham Young.

The lure of Oak Island.

Why a father buried himself alive.

Bronze Age Cheerios.

Apparitions and "Goethian science."

In other news, Queen Victoria was...odd.

In which Robin Hood writes some angry letters.

This week in Russian Weird looks at some previously unknown humans.

The Great Aurora of 1859.

Britain's Atlantis.

A brief history of quill pens.

A brief history of British poaching.

The first Duke of Edinburgh.

Medieval marital disputes really didn't kid around.

An 1880 steamship tragedy.

A life-saving nightmare.

A famous French surgeon.

A famous French murderer.

The turbulent and short life of a Welsh woman.

A look at the Martian North Pole.

And the show's over for this week! See you on Monday, when we'll meet a medieval woman scarier than anyone you'd see on "Game of Thrones." In the meantime, here's a bit of music from her era.

Wednesday, June 12, 2019

Newspaper Clipping of the Day

|

| Via Newspapers.com |

Every now and then, I come across some old newspaper story where I simply don't know what to say about it. I just post the damn thing, and move on.

This is one of those times. The (Racine, Wisconsin) "Journal-Times," February 17, 1897:

A story is related about a man who said of his married life: "The first year I thought so much of my wife I could have eaten her; the second year I wished I had."I was unable to learn if Mr. Francefort predeceased his hungry helpmate, or if such was the case, she actually went through with her desire to turn a loved one into a condiment. If she did, what came to my mind was: everything we eat eventually leaves our digestive system as...

The marital experience of Mrs. Matilda Francefort, of 8 State street, Brooklyn, has been different. For thirty years she and her husband have lived together, and during that time they have been separated only for brief intervals. Having been together in life, Mrs. Francefort does not intend to be separated from him in death, providing his demise occurs first. "I have fully resolved to have my husband cremated," says Mrs. Francefort, "and instead of burying the resulting ashes or scattering them to the winds, I shall use them as I would spice in seasoning my food."

The idea is original with Mrs. Francefort. She is a vivacious French woman, of a lively disposition, and is not at all disposed to ponder over gruesome topics. She is prepared to defend the idea of transforming her digestive apparatus into a cemetery with good logic. "I think it is a beautiful sentiment," she said, "and I believe that I set a good example to many other wives who secure divorces from their husbands. I love my husband and we have always lived together happily. Recently his health has not been good and I have been forced to think what I would do if he should die. I did not like the notion of burying him. The Idea of putting him in the ground was repugnant. Then it occurred to me to have his remains cremated, and afterward, like an inspiration, I thought that the ashes could be disposed of most suitably by using them to prepare my food. If used in small quantities they cannot possibly hurt me, and in that way we shall always be together, and we will ultimately be one in fact as well as in name."

"So you do not think that the ashes will be injurious to your health?"

"No, Why should they be? Fire purifies, and such things as microbes, which cause many of the ills of this life, could not exist in ashes produced by the tremendous heat of the crematory. I shall keep the ashes as sacred and will use only small pinches, precisely as I would pepper or spice when preparing my own food, or that of a few intimate friends. It seems to me that this is a much more satisfactory way to dispose of the remains of one I have loved during life than it would be to bury him in a grave and leave him as food for the worms."

"What does your husband think of the plan?" asked the reporter.

"He knows nothing about it," she confessed. "Anyway, when the plan is put into use he will be unable to object. I do not think he would care. anyway, and I believe he will like the idea. I certainly would be pleased at such a proof of devotion from him should I die first."

The ashes which result from the cremation of a corpse weigh from four to six pounds, depending on the size and formation of the body. Men usually furnish more ashes than women, and the spare, bony man leaves more residue than the fat one. It will thus be seen that Mrs. Francefort will secure enough ashes to fill several spice boxes, and if she uses it sparingly, as she says she will, the ashes of her husband will serve as seasoning for some months, or even years. It is the bones of the body that make the ashes. The flesh, which is composed largely of water, completely disappears, and even the clothing is consumed.

Should Mrs. Francefort survive her husband, and thus be enabled to put her plan Into operation, he will have the strangest sepulcher ever accorded to a human being in a civilized country. It will be a species of cannibalism with an up-to-date tinge that is without a parallel. Eating ashes for seasoning is not so original with Mrs. Francefort as one might think. The American Indians of Western New York, before the advent of the white man, had very little salt, and as a rule used white wood ashes on their meat in its place. Some of the early explorers tried this custom and say they liked ashes as well as salt. But human ashes are a different experiment and must first be tried.

Oh, Matilda. What a rude fate for your husband.

Monday, June 10, 2019

The Lost Boy: The Mystery of Melvin Horst

|

| Melvin Horst |

America's most famous child kidnapping case is the 1932 disappearance of the Lindbergh baby. The notoriety of this still-enigmatic crime overshadows the fact that just four years previously, another little boy vanished in an equally strange and sinister manner. This earlier case, like the hunt for Charles Lindbergh Jr., had many weird twists and turns that for some time held the nation spellbound over the fate of the child victim.

Before there was "baby Charlie," there was little Melvin.

It was two days after Christmas 1928 in Orrville, Ohio. The Horst family still had the tree and holiday decorations filling their living room, and the presents received by their three small children were scattered throughout the house. The Horsts were of modest means, but the household was a happy and comfortable one. They were an average family, living in an average town, living average lives.

On the afternoon of December 27, four-year-old Melvin Horst left his home to play with two friends in the local school yard. He carried with him a red toy truck he had received as a Christmas present. When it began to grow dark, a little after five o'clock, Melvin's friends went home to get dinner, leaving him to walk home alone. He only had to travel a little over a block, through a one-thousand-foot alleyway.

Dinnertime at the Horst household was 5:30. When Melvin failed to arrive for the meal, his parents, Zorah and Raymond, immediately began to worry. He had never been late for dinner before. All they found of their son was his little toy truck, lying on their front yard. When two hours of searching failed to find any sign of the boy, the Horsts contacted the city marshal Roy Horst, who happened to be the child's uncle. A massive hunt was launched, with authorities in the surrounding communities contacted. The local radio station broadcast a description of the missing boy. For all that night and the following day, hundreds of volunteers combed every square inch of Orrville, including wells, cisterns, and even the ice-covered pond at the edge of town. It was one of the largest manhunts in the county's history. And it came up with exactly nothing. Somehow, within just yards from his home, little Melvin and suddenly and completely vanished.

The Horsts believed someone must have kidnapped the boy, but police were more skeptical. It was no secret that the family did not have the money to pay off ransom demands. The Horsts were quiet, respectable people, with no enemies. What reason would anyone have to abduct the child?

Well, there was one obvious reason, and the authorities did pursue it. Police checked out all the known "perverts" in the area. However, all these men--who nowadays would be called "registered sex offenders"--had alibis for the time Melvin disappeared, and a search of their homes found nothing suspicious.

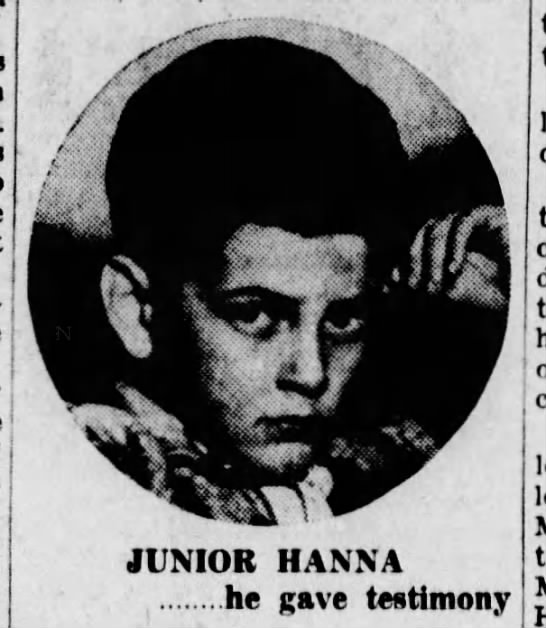

After a few days of fruitless investigation by the local police, two well-known detectives, Ora Slater and John Stevens, were called in to take over the baffling case. Almost immediately, these two men uncovered what was the first possible break in the mystery. An eight-year-old boy named Charles "Junior" Hanna came forward with a startling tale. He claimed that he had been playing with Melvin on the evening of the disappearance. As the boys prepared to go home for dinner, Junior stated that he saw Melvin enter the home of the Arnold family, which happened to back up on the alley where the child was last seen. The Arnolds were related to Junior, and the whole family had a bad reputation in Orrville. In fact, Marshal Horst had arrested a number of Arnolds for various crimes, including bootlegging and robbery. Could simple revenge be behind the mystery?

|

| Via Newspapers.com |

Police promptly arrested the Arnolds and Bascom McHenry (an Arnold son-in-law) and charged them with child stealing (which was, under Ohio law, a less serious offense than kidnapping.) Under questioning, the patriarch of the family, Elias Arnold, admitted that he "had it in" for Roy Horst, but he, as well as the rest of the Arnolds, denied having anything to do with Melvin's disappearance.

The prosecutor, Walter Mougey, knew the evidence against the suspects was slight, if not virtually nonexistent, but at the moment, it was all he had. He decided to roll the dice and take the case before a grand jury. His argument was that Elias Arnold and his son Arthur mistakenly believed that little Melvin was the son of Roy Horst, and so they kidnapped the child to get vengeance against the lawman.

The two Arnolds stood trial in March 1929. Their attorney, A.D. Metz, had little trouble making short work of the feeble case against his clients. Metz declared that the detectives framed the Arnolds so they could collect the reward money. He also blasted the prosecution for not allowing him to interview Junior Hanna, even though the boy's testimony was the sole evidence implicating the defendants. Metz also produced a witness, Ora Watts, who managed to poke a considerable hole in Junior's story. Young Hanna--in one of the numerous differing versions of his story--claimed that he had seen Arthur Arnold offer Melvin an orange. Horst had dropped the fruit in the Arnold yard when Arthur picked up the boy and carried him into the house. An orange was indeed eventually found on the Arnold property. However, Watts told the jury that he had made a minute search of the Arnold yard two days before this discovery, and he was positive the orange was not there at that time. The implication was that investigators had planted this incriminating evidence in order to corroborate Junior's story. When Elias took the stand he, naturally, denied having any knowledge of what happened to Melvin. He made no secret of the fact that he had a grudge against Roy Horst, but made the not-unreasonable remark, "If I wanted to get even with Marshal Horst, I'd take it out of his skin."

Despite the lack of solid proof against the defendants, the fact that they had no alibi for the evening of Melvin's disappearance, coupled with their generally shady history, obviously told heavily against the Arnolds. After deliberating for only seven hours, the jury found them both guilty. Elias was sentenced to spend twenty years in the Ohio State Penitentiary. Arthur, who was only seventeen, was sent to the Mansfield Reformatory.

The Arnolds vowed to fight the verdict. While their attorneys sought a new trial, the search for little Melvin continued. "For God's sake," Elias told Ora Slater, "find that boy." The publicity given the disappearance brought in the usual crop of "sightings." One witness claimed to have seen Melvin on a train in Columbus, Ohio. Another said that the boy had been hit by a car, with his body thrown into the Scioto River. Others told of seeing the child in a green car which had been seen in the area. Still others suggested that Melvin had been snatched by bootleggers fearful he would "rat" on them. None of these leads went anywhere.

The lawyers for the Arnolds went before the Ninth District Court of Appeals to ask that they be given a new trial. These three appellate judges agreed, on the grounds that Junior Hanna's testimony should not have been admitted in court. In fact, two of the judges advocated that all charges against the Arnolds should be dropped, but this would have required a unanimous decision from the court.

The second trial took place in December 1929. It was essentially identical to the first proceedings. The prosecution claimed that the Arnolds abducted Melvin in order to get their revenge against Roy Horst. The defense argued that the Arnolds had been framed. They also proved that Junior Hanna had changed his story no less than five times. In one statement, Junior said he had seen Arthur carry Melvin into the Arnold home. In another, he said only that he had seen Melvin and Bascom McHenry in one of the windows of the Arnold home. In yet another, Junior stated that he had left for home before Melvin entered the alleyway. Some days, Junior said Bascom and Arthur abducted Melvin. On other days, Arthur and Elias did the dark deed. Which one of Junior's statements was the truth? Were any of them the truth? Junior was also asked why he had waited until four days after Melvin vanished to tell what he had allegedly seen.

"Because nobody asked me," the boy replied.

Naturally, the defense made much of the fact that Junior Hanna's ever-shifting and highly untrustworthy testimony was the sole piece of evidence against the Arnolds, and this time, the jury was sympathetic to their argument. After six hours of deliberation, they returned a verdict of "not guilty."

The next bizarre chapter in the story came when Junior Hanna came up with a fresh new tale: this time, he accused his own father, Charles Hanna, of Melvin's murder. Under intense questioning by the police--which probably included techniques that would be frowned upon by civil libertarians--Hanna Senior signed a confession. His story was that an Akron bootlegger named Tony La Fatch mistakenly believed that Melvin was Roy Horst's child. La Fatch offered a payment of 25 gallons of liquor to anyone who could deliver to him the hated marshal's son, dead or alive. Hanna went on to say that he witnessed a friend of his, Earl Conold, kidnap the child and strangle him to death, after which the child was buried in Hanna's back yard. The infuriated Conold responded by accusing Hanna of the boy's murder. While all this finger-pointing provided a great deal of lurid newspaper copy, the police had a hard time finding any sort of actual evidence that either man had anything to do with Melvin's disappearance. An excavation of Hanna's property found nothing. Before long, Hanna withdrew his confession, stating that he had only signed it to end three days of brutal interrogation, and both men were eventually released from police custody. Once again, an initially promising lead went nowhere.

The hunt for Melvin went on. Investigators spent days sifting through the numerous sightings, local rumors, tips, and, in some cases, outright hoaxes that streamed into the prosecutor's office. The Horst family refused to take down their Christmas tree, insisting that it would remain until Melvin came back home. Zorah Horst vowed that the family would never celebrate another Christmas without him. Melvin's relatives believed that he had been kidnapped by bootleggers who kept the boy alive. In 1943, Roy Horst theorized, "The hijackers caused more of a sensation than they intended, and feared to return the lad...but they wouldn't kill him and get themselves in any deeper...He probably was passed from one bootlegger to another until they lost all idea where he came from...and now he's probably in the army."

The sad, dried up Christmas tree--symbol of a small boy's last holiday--was fated to stand for a very, very long time. Months, then years, went by, without anyone finding the slightest trace of Melvin. In 1940, the governor of Ohio ordered that the investigation be re-opened, but this second inquiry was no more fruitful than the first. Up until his death in 1961, Melvin's father continued the search for his son, pursuing every possible clue he could find, no matter how unlikely.

Nearly a century has gone by, without anyone being able to offer the answer to one very simple question: "What happened to Melvin Charles Horst?"

Friday, June 7, 2019

Weekend Link Dump

This week's Link Dump asks you to give a warm welcome to the latest members of Strange Company HQ's research staff!

Where the hell are all the extraterrestrials?

Murder on Delaware Avenue.

A possible explanation for ball lightning.

The days of telephone newspapers.

The days of impotence trials.

This week in Russian Weird examines the time an alien being came to visit.

A seminal (and extremely long-winded) Tudor play.

The Thames and its influence on William Morris.

A ghostly wedding.

What it was like to eat out in Victorian England.

What it was like to visit 17th century Barbados.

A cursed farm.

A Napoleonic exile in America.

Was Errol Flynn a Nazi spy?

Tramp cats take over a New York tenement.

Why there was a time you'd want to order the world's worst sandwich.

A brief history of straw plaiting.

Yet another stone-throwing ghost.

Nero's secret chamber.

Prehistoric witnesses of a volcano eruption.

Contemporary newspaper reports of D-Day.

George III's 70th birthday celebration.

The mysterious death of Baby Frankie.

A legendary haunted Los Angeles house.

Why it's a good idea to listen to The Voice.

Percy Fawcett and the man-apes.

Why it's not a good idea to have yourself buried alive. Especially when you have a conscientious sexton.

18th century melancholia.

Reminiscences of a D-Day survivor.

A strange disappearance in the Amazon.

The city of cat ladders.

What Princess Charlotte of Wales did with her pocket money.

The kind of thing that happens when you get hit by a stone bullet.

Don't believe everything you read. Hell, at this point I'm opting for "don't believe anything you read."

A nurse sees a ghost.

A 17th and 18th century spa town.

That's it for this week! See you on Monday, when we'll look at a child's strange disappearance. In the meantime, here's the Scottish Fiddle Orchestra. One hundred thousand welcomes to you!

Wednesday, June 5, 2019

Newspaper Clipping of the Day

|

| Via Newspapers.com |

It is not uncommon for people who have had organ transplants or massive blood transfusions to report that they to some extent "take on" memories, or even personality traits, from their donors. (I myself know two people who claim this happened to them.) The following story, however, takes this alleged phenomenon to a whole 'nother level. The "Baltimore Sun," August 25, 1925:

London, Aug. 25.--Physicians and psychologists throughout England today are interested in a strange telepathy by which Frederick George Lee, professional supply source for blood transfusions, gets death messages from those his blood should save.

Lee, an ex-army sergeant, is employed at the Middlesex Hospital, and has given his blood twenty-four times since 1922 for transfusions. Seventeen of the patients have lived; the other seven died.

In each of the seven eases, at the exact instant of the patient's death, Lee has felt a severe pain in his arm and has immediately been overcome with illness. By these symptoms he knows that the patient has passed on. What makes his case all the more strange is the fact that Lee never sees the patients to whom his blood is given.

Lee started his career as blood "transfusioner" three years ago. Applying at a labor bureau for work, he was asked if he would give his blood to save the life of a 10-year-old girl at the Middlesex Hospital.

"I've kiddies of my own at home," he replied, "and if you think it would help her. I'll do it."

Since then he has been providing his blood for patients in the hospital. Lee is 34 years old, and has had no serious inconvenience from his sacrifice of thirty-six pints of blood beyond the pain and nausea at the time of a patient's death.

Scientists are puzzled at the strange phenomenon.

Monday, June 3, 2019

Carl Jung's Ghost Story

It is well known that the famed psychiatrist Carl Jung had an intense interest in paranormal phenomena, most notably what is generally called "synchronicity." He had a number of personal encounters with the occult, one of the most interesting of which was included in Fanny Moser's book, "Ghost: False Belief or True?"

In the summer of 1920, Jung was invited by a man he called "Dr. X" to give some lectures in London. His friend found him a place to stay during his weekends off--a cottage in the peaceful Buckinghamshire countryside. "Dr. X" did not have an easy time finding Jung lodgings, as it was so close to the summer holidays that most desirable places had already been let. Then, at the last moment, he was lucky enough--or so he thought at the time--to find a charming old farmhouse at an astonishingly low price. "X" hired a cook and charwoman, and all was set.

When Jung first saw the place, he was delighted. It was a spacious two-story house with a conservatory, kitchen, dining-room, and drawing-room. The bedroom set aside for Jung was so roomy, it took up an entire wing of the house. Jung's first night there was uneventful.

On the following night, he retired at 11 p.m. Although he had been tired, he found that once he was in bed, he was having a hard time getting to sleep. Instead, he fell into a "kind of torpor" that was extremely unpleasant. Also, the room seemed strangely stuffy, with an "indefinable, nasty smell." This was odd, as both bedroom windows were wide open to let in the warm, pleasant summer air. Jung remained in this uneasy trance-like state until dawn, when the feeling suddenly passed. He found himself able to sleep peacefully until 9 a.m.

That evening, Jung told "Dr. X" of his bad night. The doctor prescribed drinking a bottle of beer before bed.

In spite of this sage advice, Jung's night was a replica of the one before: paralyzing torpor, inexplicably stale air, a sickening smell that he could not identify...until he recalled a patient he had years before, an old woman dying of an open carcinoma. He realized that her hospital room had that same vaguely repulsive odor. "As a psychologist, I wondered what might be the cause of this peculiar olfactory hallucination. But I was unable to discover any convincing connection between it and my present state of consciousness."

Then Jung noticed a fresh bit of weirdness: the sound of dripping water. It was like a leaking tap...except there was no running water in his room. Rain? But the day had been clear and sunny. He managed to shake his lethargy enough to light a candle. He saw no water on the floor, and the ceiling was dry. He looked outside at the cloudless sky.

He continued to hear dripping sounds. They seemed to emanate from a place on the floor about eighteen inches from the chest of drawers. Then the sounds abruptly stopped. Again, he was unable to sleep until the first light of dawn, when he fell into a deep slumber.

It was not exactly the relaxing weekend in the country he had bargained for.

Jung spent the work week in London, where he was too busy to think of the curious events of the past weekend. Late Friday, he returned to the cottage expecting all to be normal.

However, as soon as he retired to bed, the events of the previous weekend made an encore appearance: torpor, disgusting smells, dripping water, the whole package. Only this time, even creepier elements arose. Jung heard something brushing along the walls. The furniture began creaking. There were ominous rustling noises in the corners. When he lit a candle, the noises and smells disappeared, but the moment he returned the room to darkness, the creepy phenomena immediately returned, not leaving until the first light of day. The next night, the same sensations returned, in an intensified form.

It was at this point that Jung acknowledged that something seriously weird was going on. Unfortunately, he had no idea what it might be.

On the third night, he was greeted by loud knocking noises, as if some animal was running frantically around the room. By the following weekend, he was hearing "a fearful racket, like the roaring of a storm...Sounds of knocking came also from outside in the form of dull blows, as though somebody were banging on the brick walls with a muffled hammer."

On his fourth weekend at the cottage, he delicately hinted to his host that perhaps the reason such an outwardly desirable residence was let for such a ridiculously low price was because the place was haunted. "Dr. X," a solid materialist, scoffed at such superstitions...although it was curious how the two village girls they had hired to cook their meals and clean the cottage always insisted on leaving well before sundown. When Jung ventured to joke to the cook about how she must be afraid of him, the girl laughed. She was not the least bit nervous about him and "Dr. X.," she assured him, but there was nothing that would induce her to be alone in this cottage, particularly at night.

"What's the matter with it?" Jung asked.

"Why, it's haunted, didn't you know?" she replied. "That's the reason why it was going so cheap. Nobody's ever stuck it here." She knew no reason for the cottage's sinister reputation. It just had an evil air to it for as long as she could remember.

Jung was now determined to get to the bottom of the haunting. He persuaded the still-skeptical "Dr. X" to help him make a thorough search of the cottage. Nothing unusual was found until the two men examined the attic. They found a dividing wall between the two wings of the house. In it was a door, clearly newer than the rest of the old cottage,with a heavy lock and bolts that shut off the wing where the men were living from the unoccupied part.

This made no sense. On the ground floor and the first floor, the two wings were able to freely communicate with each other. There were no rooms in the attic to shut off. Why was this door put in?

Jung's fifth weekend at the cottage was the worst of all. After enduring the now-routine nighttime sluggishness, mustiness, smells, rustlings, and creakings, he heard something new: the sound of loud blows against the walls. He got the sudden sense of someone standing very near him. He opened his eyes, and immediately wished he hadn't. Next to him on the pillow was the head of an old woman, her right eye glaring at him. Or, rather, part of a head. The left half of her face was missing.

Jung leaped out of bed. He spent the rest of the night in an armchair, making sure his candle remained lit. When morning came, he insisted--rather late in the story, I would think--on sleeping in another room. In his new bedroom, he slept soundly and utterly undisturbed.

Jung began to get irritated at "Dr. X's" continued calm skepticism about his experiences. He dared his friend to spend a night in the haunted room. "X" smilingly agreed. He even volunteered to spend the weekend alone in the cottage, in order to give Jung a "fair chance."

Ten days later, Jung received a letter from "Dr. X." As agreed, he had spent a solitary weekend in the cottage. His first night there was spent in the conservatory--he figured that if the cottage boasted a ghost, the spirit could manifest itself anywhere. As soon as he fell asleep, he was awakened by the sound of footsteps in the corridor. He instantly lit a candle and flung open the door, but he saw nothing. Silently cursing Jung for being a superstitious fool, he went back to bed.

As soon as he settled down, the footsteps returned. They stopped right in front of his closed and barricaded door. He heard creaking sounds, as if someone in the hallway was pushing against the door. "Dr. X" retreated to the garden, where he was able to sleep in peace.

"X" informed Jung that he had given up the cottage.

His friend's report gave Jung "considerable satisfaction after my colleague had laughed so loudly at my fear of ghosts." A short while later, Jung heard that the cottage had been demolished, as the owner was finding it impossible to sell or rent out the place.

The best explanation Jung could offer for his eerie experiences was that he experienced a sort of "subliminal intuition," that "my presence in the room gradually activated something that was somehow connected with the walls...If the olfactory organ in man were not so hopelessly degenerate, but as highly developed as a dog's, I would have undoubtedly have had a clearer idea of the persons who had lived in the room earlier.

"Primitive medicine-men can not only smell out a thief, they also 'smell' spirits and ghosts." Perhaps, Jung mused, the sickening odor of the room embodied "a psychic situation of an excitatory nature and carried it across the the percipient." "This hypothesis naturally does not pretend to explain all ghost phenomena, but at most a certain category of them...Our unconscious, which possesses very much more subtle powers of perception and reconstruction than our conscious minds, could do the same thing and project a visionary picture of the psychic situation that excited it."

Jung concluded, "These remarks are only meant to show that parapychology would do well to take account of the modern psychology of the unconscious."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)