|

| "Wichita Beacon," June 1, 1911, via Newspapers.com |

Rather amazingly, Gertrude Gibson Patterson was not the most scandalous murderer gracing Denver in 1911. That dubious honor went to Frank Harold Henwood, who found a deadly way to end an increasingly troublesome love triangle.

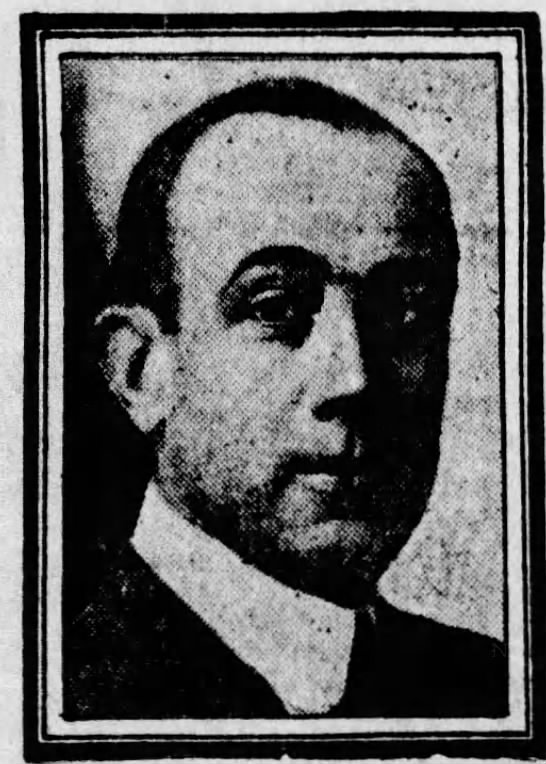

The road to murder began a few years earlier, when a wealthy Denver widower, John W. Springer, met a beautiful, much-younger divorcee named Isabel Patterson. (She was no relation to Gertrude, although the two women were definitely kindred spirits.) Although Springer was soon given abundant warning that the lady had acquired a decidedly questionable reputation, the infatuated banker married her anyway. "Sassy" as he nicknamed her, was lively, Sassy was charming, and he felt she would bring some much-needed warmth and excitement to his dull life.

|

| Isabel Springer, via Newspapers.com |

Sassy was indeed nothing but excitement, but not of the sort he probably expected. The new Mrs. Springer soon demonstrated that the slurs on her character were not unjustified. Marriage did nothing to curb her taste for drugs, disreputable parties, and raffish companions. Life on her husband’s ranch was not to her taste, so she persuaded him to rent her a suite in the Brown Palace Hotel. She spent most of her time there.

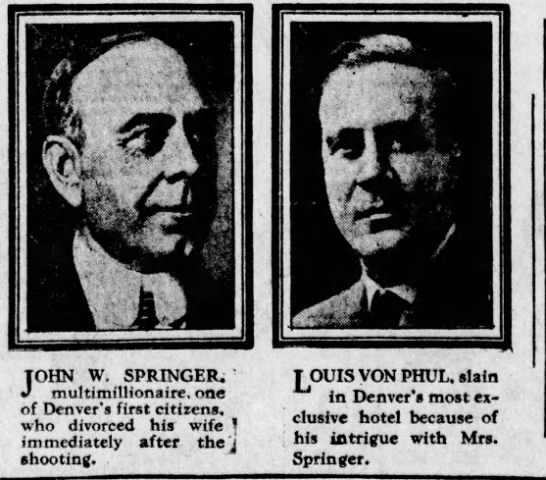

In the spring of 1911, she entered into a flirtation—or perhaps something even more improper—with a handsome rake named Sylvester “Tony” Von Phul. Mrs. Springer also became involved with Frank Henwood, her husband’s new business partner. This relationship probably developed into a full-blown affair. (John Springer, a remarkably oblivious sort for a successful businessman, evidently overlooked—or wished to overlook—his wife’s activities.)

|

| Frank Henwood |

Von Phul found himself displaced in Mrs. Springer’s affections, and, according to her, he did not take his dismissal well. He had what the lady described as “silly little letters” she had written him. She told Henwood he was threatening to make them public if she did not resume their relationship.

Henwood—motivated, so he later claimed, only by a gallant desire to defend the honor of his friend’s wife—resolved to have it out with the blackmailer. On May 23, 1911, Von Phul returned to Denver from a business trip and registered a room at the Brown Palace. That day, the two men had a confrontation in Von Phul’s room. According to Henwood, he implored his adversary to return Mrs. Springer’s letters and stay out of her life. Von Phul, in the true fashion of stage villains of the era, contemptuously slapped him.

Henwood endeavored to keep his temper. He had had trouble in the Brown Palace before, for “beating small bellboys,” not to mention attempting to force his way into the room of a certain female guest. He feared a third incident might find him barred from the hotel permanently. The fact that he knew Von Phul was carrying a gun might also have had a restraining effect.

The two men continued their quarrel, until Von Phul ended the debate by hitting Henwood with a shoe-tree and displaying his pistol in a menacing manner. Henwood staggered out with the humiliating knowledge that he had little talent either as a diplomat or a tough guy.

According to Mrs. Springer’s later testimony, Von Phul then marched into her suite. He denounced her for allowing Henwood to interfere with their romance, and—not for the first time—struck her in the face. After tearing up a photograph of Henwood that was on her dresser, he stalked out, vowing to “fix” his rival.

The atmosphere in the Brown Palace’s dining room that evening must have been enough to give anyone indigestion. Henwood ate his dinner with Von Phul sitting nearby “sneering” at his vanquished foe. Mr. and Mrs. Springer ate together at a third table. After what I assume was a singularly dismal meal, Henwood went to share his troubles with the police chief and ask him to run the gun-toting Von Phul out of town. It took more than gun-pointing and shoe-tree assaults to impress a Colorado policeman of the day. Chief Armstrong refused to do any more than suggest Henwood simply stay out of Von Phul’s way and allow the Springers to handle their own personal issues. For the second time that day, Henwood was forced to make an ignominious retreat.

The next morning, according to Isabel Springer, Von Phul again accosted her with threats of “fixing” the busybody Henwood. She then sent Henwood a note imploring him to just wash his hands of the matter and allow her to handle her own troubles. Instead, Henwood went running back to Chief Armstrong, who again shrugged that he could do nothing unless specific charges were filed against Von Phul. Henwood then purchased his own ally, in the form of a .38 revolver.

That evening, Henwood accompanied the Springers to the theater. After the trio returned to the Brown Palace, the Springers went to their suite while Henwood retired to the bar, accompanied by his brand-new gun. Shortly before midnight, Von Phul entered the barroom. He sidled up to Henwood and made a remark to him. Its exact nature is lost to history, which is just as well, as it was evidently thoroughly unrepeatable.

What happened next is unclear. Some witnesses say Von Phul then turned his back on Henwood and calmly ordered a drink. Others in the bar—most notably Henwood himself—stated that Von Phul knocked Henwood to the floor and then stood over him in a very threatening manner. All we know for certain is that Henwood pulled out his gun and frantically, blindly, fired every bullet in the chamber. Two of the bullets hit Von Phul, while the others flew wildly across the barroom, wounding two utterly innocent bystanders. Once his gun was empty, Henwood staggered off to the hotel lobby and quietly waited to be arrested.

Both Henwood and his injured enemy tried to keep Isabel Springer’s name out of the police investigation, but that, of course, was impossible. Most of Denver knew about her consecutive—or simultaneous—relations with the two men. Von Phul died the next morning, insisting sardonically that his quarrel with Henwood had arisen over a difference of opinion over the bathing beauties appearing in the Follies of 1910. Henwood, sitting in his jail cell, refused to say much of anything at all. The nearly-forgotten third man in Isabel’s life—namely, her husband—maintained that she could have had nothing to do with the shooting, and that Henwood was a “good fellow” whose friendship with Isabel had his complete approval.

No one knew what Isabel Springer herself had to say about the matter. She had gone into hiding.

Before Henwood came to trial, one of the unlucky onlookers he had shot, G.E. Copeland, died of gangrene, so he wound up facing two charges of murder. Less than a week after this second death, John Springer quietly filed for divorce.

Probably in a misguided attempt to protect the Springers, the D.A. first tried Henwood only for Copeland’s murder. This made little sense, as the law held that Henwood would only be guilty of killing Copeland if it could be established that the death occurred because Henwood was busy trying to murder someone else. In other words, Henwood could only be convicted of Copeland’s murder if the D.A. proved he killed Von Phul as well.

During this trial, both Henwood and Mrs. Springer attempted to present their relationship in the most innocent way possible, but the effect of this discretion was damaged by a couple of the Springers’ servants, who eagerly gave some juicy testimony about the indecent familiarity between the pair. Henwood made a good witness for himself. He stubbornly maintained that the shooting was a matter of self-defense, arising from his efforts to protect his best friend’s wife from a blackguard.

The jury found him guilty of second-degree murder. The D.A. immediately told the judge of his plans to put Henwood on trial again for the killing of Von Phul. Henwood’s attorney argued that this would constitute double jeopardy, as the two deaths were effectively “one and the same case.” He declared that if Henwood were acquitted for killing Von Phul, he would seek his client’s release. “If he is innocent of murdering Von Phul, he cannot then be guilty of murdering Copeland.”

This logic persuaded the D.A. to leave well enough alone. He dropped the idea of pressing the Von Phul murder against Henwood. Several weeks later, when Henwood appeared for sentencing, he gave the judge what was either one of the bravest or one of the stupidest speeches ever given in a courtroom by a convicted murderer. When asked if he had anything to say before sentence was passed on him, Henwood wound up fulminating for half an hour. He called the judge “prejudiced.” “I never expected justice from the start.” He still thought of John Springer as a friend, and regarded Isabel as a sister. Henwood accused the judge of acting as a prosecutor during the trial, of intimidating Mrs. Springer, of believing that he was a home-wrecker “although God knows I was not.” He closed by saying calmly, “Now I am ready for your unjust sentence.”

After a lengthy silence, the judge coolly imposed his sentence: It was the maximum. Life imprisonment. No one knows if he reached this decision before or after Henwood’s diatribe.

This was hardly the end of Henwood’s legal battles. While he sat in the County Jail—treated, said a reporter, as “a sort of matinee idol”—his appeal was heard by the state Supreme Court. In January 1913, the court ruled in his favor, on the grounds that the trial judge had unjustly deprived him of the chance to be found guilty of manslaughter. A retrial was ordered. In the meantime, Henwood’s attorney succeeded in his motion to have the Von Phul charges dropped. He then argued that this dismissal amounted to an acquittal in the death of Copeland. This motion was dismissed, and in May Henwood faced his second trial. It was basically a rehash of the first until the defense startled everyone by calling John W. Springer to the stand.

Springer—who had visibly aged in the last two years—made the best character witness any murderer could ask for. With calm dignity, he testified that Henwood was “a gentleman” whose relations with Springer’s now ex-wife had been entirely proper. When he left the stand, Springer walked across the courtroom and paused to warmly shake Henwood’s hand before exiting.

It is hard not to think that John W. Springer was the biggest fool on two feet.

The defense, obviously believing they now had an acquittal in the bag, rested their case on this note of Hollywood melodrama.

It is always a mistake for an attorney to take a jury for granted. The panel essentially took Springer’s testimony—handshake and all—and chucked it out the deliberating room window. They found the defendant guilty of first degree murder. He now faced the death penalty. When the verdict was read, Henwood burst into tears, while his lawyer sat looking as though the jurymen had hit him over the head with a shoe-tree.

After several efforts to appeal the verdict had been denied, Henwood’s lawyer made a last-ditch effort with Colorado’s governor. This was more successful. Governor Ammons commuted the sentence to life imprisonment. Henwood served ten years in the state penitentiary before being paroled. Unfortunately, his years in prison had seen a rapid deterioration in a mental equilibrium that was clearly none too steady to begin with. As miserable as prison life had been, he was even less suited for freedom. Soon after his release, he was taken back into custody for assaulting a waitress. This was seen as a violation of his parole, and he returned to the penitentiary until his death in 1929.

The former Isabel Springer had an even more unhappy end. After her divorce, she drifted to New York. She made fitful attempts to become an actress or an artist’s model, but her only success was in sinking deeper and deeper into alcoholism and drug addiction. According to some reports, the former high society femme fatale became a street prostitute. She died penniless in a hospital charity ward in 1917 at the age of thirty-seven.

John Springer lived, reputation and dignity more-or-less intact, until 1945. In 1915, the fifty-six year old entered into his third marriage, with a Janette Lotave. For the second time in a row, he wed a lovely siren young enough to be his daughter.

Some men never learn.

Usually, someone comes out of these disasters ahead of the game, often, unjustly, it is the villain. But no one survived this one. Even Springer, as you rightly judged, a fool, was made to (or made himself) look ridiculous - probably more so after his third wedding.

ReplyDelete