|

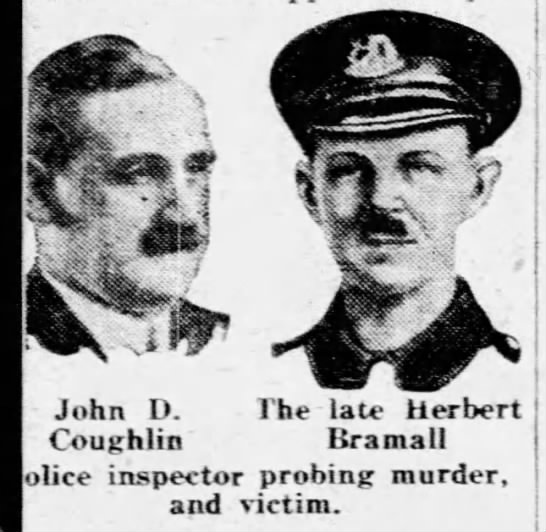

| "New York Daily News," January 27, 1926, via Newspapers.com |

Perhaps the most famous cliche involving murder mystery novels is “The butler did it!” In one long-forgotten real-life slaying, someone did it to the butler.

Herbert Bramall, who was born around 1889, was the quintessential British household servant. He first entered domestic service as an employee of the Duke of Cumberland. He then served in WWI, where he earned several commendations for bravery. In the army of occupation, he acted as a machine gun instructor.

In 1920, he emigrated to America. Bramall found employment in the Philadelphia household of Anthony J. Drexel Biddle, after which he moved to New York City. In 1923, Bramall entered the household of the wealthy lawyer James R. Deering. Bramall’s new wife, Bertha, was a maid in the same establishment. Bramall was, by all accounts, a gem of a butler: hard-working, trustworthy, and efficient. He enjoyed the full confidence of all his rich and powerful employers. He was described as “a home-loving and peaceable Englishman of the servant class, who made few acquaintances.”

The night of January 24, 1926, began as a very quiet one in the Deering household. Deering himself was in Atlantic City on a business trip. Mrs. Deering, her 13-year-old son, and a family friend chatted casually in an upper parlor. Downstairs, the cook, Frances Lovett, was puttering around in her kitchen. Bertha Bramall left for a walk--she mentioned she might take in a movie--while Herbert, his duties for the day virtually complete, enjoyed a moment of relaxation.

At 8:50 p.m., just five minutes after Mrs. Bramall’s exit, the doorbell began to ring, in an unusually prolonged manner. Bramall went to greet this very insistent caller. Just a few seconds later, the cook heard a gunshot. And seconds after that, the butler staggered through the door of the kitchen, falling dead at her feet. The screaming Mrs. Lovett immediately ran to her mistress, who summoned police. Detectives arrived fifteen minutes later. At 9:20, Mrs. Bramall returned to find that in her absence, the peaceful household had been transformed into a murder scene. When she saw policemen surrounding her husband’s dead body, poor Bertha began shrieking hysterically.

From the very beginning, investigators were baffled by this seemingly utterly senseless killing. Their obvious first move was to investigate if this murder was a personal attack. Was there anyone who had a grudge against Bramall? However, the butler’s personal history was frustratingly immaculate. He had never been in trouble with the authorities, was happily married, and, as far as anyone knew, had zero enemies.

A rich and influential attorney, it was reasoned, surely attracts ill-wishers as easily as honey draws flies. Did an assassin go after James Deering, only to shoot his butler by mistake? The obvious flaw with that theory was that it would be a markedly incompetent murderer indeed who could mistake the high-flying lawyer for a servant in full livery.

Was this an attempted burglary? But if that was the case, why did the assailant not even try to enter the house? The murderer simply shot Bramall the instant he opened the door, then vanished into the foggy night, like a malevolent phantom. Although there were hundreds of people crowding nearby Fifth Avenue, no one reported seeing anything unusual.

This inexplicable murder in the middle of the city’s wealthiest residential area was naturally alarming to New York’s elites. Was no one’s mansion safe from attack? For a few days, this unusually baffling crime was a top headline in New York papers, but after failing to uncover even a single clue suggesting who had slain the butler--not to mention why--Bramall’s death soon faded from headlines, and public memory. As far as I know, the last published reference to the murder was in 1938, when James Deering was sued by a former maid for back wages.

Poor old Herbert Bramall has languished in oblivion ever since.

It may interest your readership that the briefly mentioned Anthony Drexel Biddle was the great grandson of the president of the Second National Bank, Nicholas Biddle with whom Edgar Poe has a mysterious connection. Poe had a cousin who was an officer of the bank. Andrew Jackson, who Poe surreptitiously attacked in several stories, abolished the bank and monetized gold for exchange that brought on a deep depression. Biddle was also a publisher of Lewis and Clarke’s journal, whom Poe turned to for help. Then there was Poe’s Journal of Julius Rodman, that was used by some members of Congress to support claims in the northwest against the British...

ReplyDeleteYes, I remember that name's connection to Poe! Edgar does pop up in the most unexpected places, doesn't he?

DeletePerhaps the visitor who rang the doorbell so insistently was one of Deering's clients, who was wanted by the police and desperate to see a lawyer before he was arrested. He might then have mistaken Bramall's uniform for a police uniform and shot him in a panic, thinking that he had walked into a trap.

ReplyDeleteMaybe the wife? If not her, possibily she put someone up to it?

ReplyDeleteThat did cross my mind, if only because when a married person turns up murdered, the spouse is the natural first suspect. And it is interesting that she was away from the house at the time of the shooting. All I can say is, no one seems to have felt there was any reason to investigate the possibility.

Delete"And it is interesting that she was away from the house at the time of the shooting."

DeleteCreating an alibi for herself while a hitman killed her husband?

The Wife Did It was also my thought. Could her leaving the house, at an oddly late hour for a walk and a movie (and then she didn't go to the movie but came back soon afterwards...) have been a signal to the killer to make the hit?

DeleteAn unsolved murder is bad; a forgotten unsolved murder is sad. I was going to add that it’s worse when there seems to be no motive, but that is one of the reasons why the killing went unsolved, I imagine. As an aside, I always thought being a butler might not be a bad job; it depends on one’s employer, of course, but then contentment in any job depends on that…

ReplyDelete