|

| Arthur Brown, via Wikipedia |

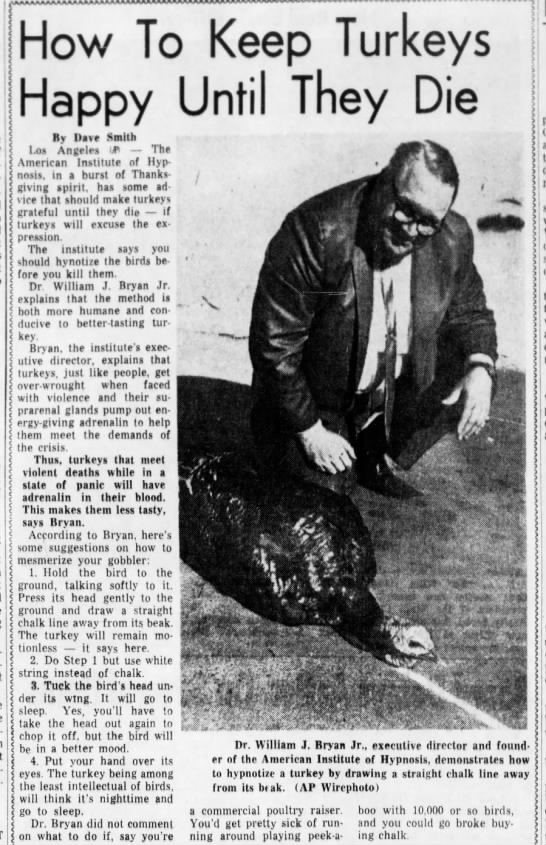

As all regular readers of this blog know, I am a sunny optimist who likes to showcase the bright side of life and human nature at its inspiring best. So you can imagine how thrilled I am at the opportunity to introduce you to Utah Senator Arthur Brown, a worthy whose personal life can be most charitably described as “lively.”

So, buckle up: his story is a very bumpy ride.

Arthur Brown first made his name as a successful attorney in Kalamazoo, Michigan. His marriage, unfortunately, was less rewarding. When his wife found out that he had a mistress, Isabel Cameron, (who was enjoying a fine house provided by Brown,) Mrs. Brown cornered Mr. Brown in his office and made a nearly-successful attempt to shoot him. (Spoiler: this is the first time, but far from the last, that Brown’s lady loves used him for target practice.) After this event, Brown thought it best to get out of town. In 1876, he moved to Salt Lake City. Cameron soon joined him there. After a few months, Brown divorced his wife, and he and Isabel wed. They had one son.

|

| Isabel Cameron, via Wikipedia |

Brown’s scandalous personal life had surprisingly little effect on his professional success. He became one of the city’s top lawyers, and soon entered the political world. He served as a Utah senator from 1896-97. At the 1896 Republican National Convention, which was held in St. Louis, Isabel introduced her husband to a friend of hers, Anna Bradley, a married mother of two children.

Isabel obviously never heard the truism, “If he cheated on her, he’ll cheat on you.” Before too long, Mrs. Bradley was Brown’s new mistress. In 1900, Anna gave birth to a son, whom she named “Arthur Brown Bradley.”

She made no direct announcement who the child’s father was, but with that name, I suppose she thought it wasn’t necessary.

|

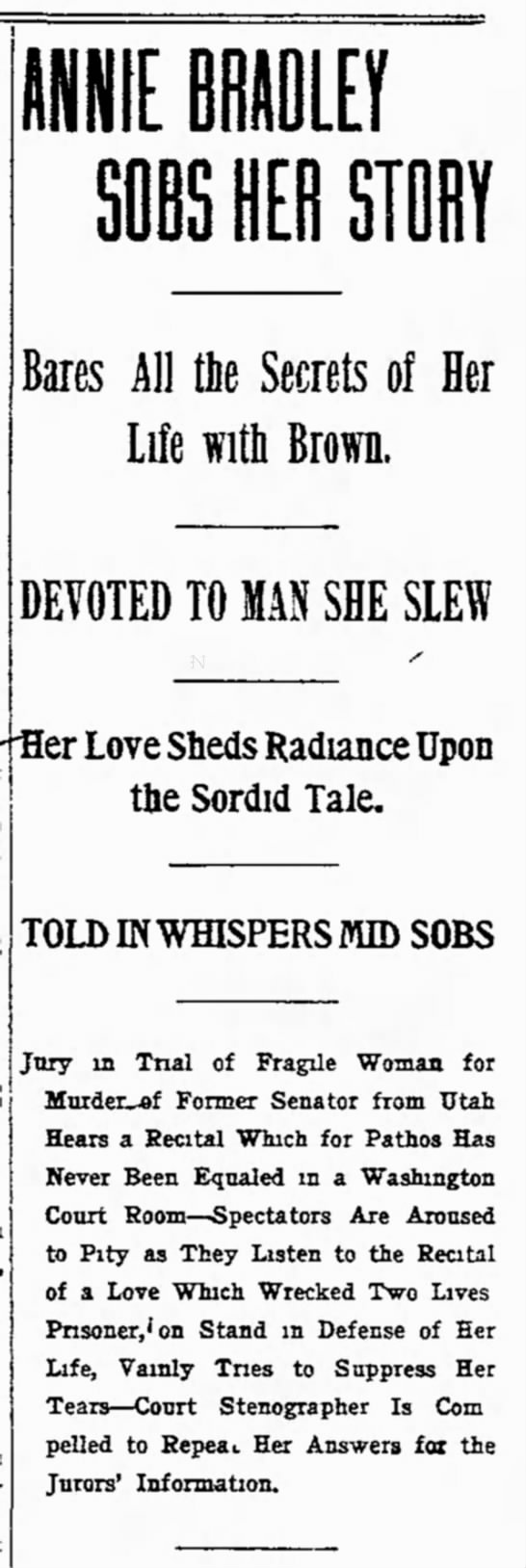

| "Washington Times," July 12, 1907, via Newspapers.com |

Not long after the boy’s birth, Brown and Mrs. Bradley eloped to Los Angeles. Believe it or not, this seems to have been Isabel’s first clue that her husband might not be a model of fidelity. At the same time, she learned that Brown had secretly been keeping an apartment which he used as a love nest. Isabel broke into the apartment to do a bit of sleuthing. There, she found a large stack of love letters written to Brown from Mrs. Bradley. They were in code, but Brown had helpfully left a paper containing the key. Isabel got to work deciphering the letters. And the more she read, the more she seethed.

Isabel sent Brown a collect wire message, one so long it cost him ten dollars. For connoisseurs of vituperation, it was worth every penny, although I doubt the recipient saw it that way. According to news reports, she called her husband every name in the book, a few that the book would have blushed to include, and vowed revenge. As an exquisite touch, Isabel wrote the message in Brown’s secret code. Then, she had Brown and Mrs. Bradley arrested for adultery. These charges were eventually dropped, but Isabel successfully sued Arthur for $150 a month spousal support. (He refused to pay, which led him to be imprisoned for contempt of court until he gave in.)

This lawsuit also included the agreement that Brown would part from Mrs. Bradley. However, the adulterous pair soon violated these terms by running off together to Pocatello, Idaho. When Isabel heard of this, she went to Pocatello--accompanied by her lawyer--to confront them.

This meeting went as well as you would expect with this crowd. Arthur haughtily told Isabel that as she had broken up his first marriage, she was hardly in a position to cast stones at Anna. Isabel responded by trying to kill Mrs. Bradley, and might well have succeeded if her lawyer hadn’t intervened. The melee ended with Isabel announcing she never wanted to see either Arthur or Anna again (a sentiment they surely heartily endorsed) and stomped back to Salt Lake City.

A few months later, for whatever inexplicable reason, Brown and Anna also returned to Salt Lake, taking up residence at the Independence Hotel. Isabel immediately sicced detectives on them, and when the pair were caught together in Brown’s hotel suite, had them charged with adultery. Mrs. Bradley pled guilty, but she was released on her own recognizance. Brown, who pled not guilty, was acquitted. The jury’s verdict looked even quainter when some weeks later, Anna gave birth to their second son. Isabel celebrated this happy event by following Anna to Brown’s office, where she beat Mrs. Bradley with a lasso. (Arthur himself was present, but apparently did not get involved with the fight. Perhaps he was hiding under the desk.) After this incident, Brown gave Anna a gun to protect herself from his wife. He would eventually greatly regret this act.

Isabel still wanted this exemplary spouse back, thus proving that people are weird. She blackmailed Arthur by threatening to publish Anna’s letters if he didn’t return to the marital home. Arthur moved back in with his wife, but the marriage was soon ended for good when Isabel died of cancer in August 1905.

After Isabel’s death, Arthur proposed to Mrs. Bradley, although she was still legally married. After she got a divorce, she naturally assumed that Brown would follow through with his promise to finally make her an “honest woman.” But, as usually happens with men of Arthur Brown’s type, matrimony was more appealing to him in theory than in reality. Whenever Anna brought up marriage, he dithered and tried to change the subject.

Arthur’s history had an odd way of repeating itself. Mrs. Bradley did a secret search of Brown’s hotel room in Washington D.C.’s Raleigh Hotel, where she found a cache of love letters written by one Anna C. Adams. (A side note: she was the mother of popular actress Maude Adams.) And they weren’t written in code.

We do not know the precise contents of these letters, but they were enough to make Mrs. Bradley get out her gun. On December 8, 1906, she went to Brown’s room and, without much ado, shot him through the abdomen. When she was arrested, Anna dismissed the matter as just another lover’s tiff. “Everything will come out all right,” she blithely told reporters. “Senator Brown will recover and I will never be placed on trial.” She added, “I abhor acts of this character, but in this case it was fully justified.” Her hospitalized victim showed an equal disinclination to take the matter seriously. He flatly refused to give a statement on what had happened. (To be fair, the situation demanded a lot of explaining.) Brown died two days later, refusing to the last to say a word about why he had been shot.

It soon became evident that he really didn’t need to. The newspapers soon happily revealed every sordid detail. Brown and his paramour provided material that most reporters just dream about covering. The press coverage of the pair’s many peccadillos had a positively ecstatic tone.

Journalists were even happier when they learned that Brown had left this world true to form. His will, dated August 24, 1906, was a masterpiece of--in the words of one reporter--”post-mortem revenge.” He asserted that neither of Anna’s illegitimate children were his, and even if they were, they would not get a dime of his $70,000 estate. He added that he never had any intention of marrying Anna, and if she tried to say otherwise, his executors were to fight those claims. All of his money was left to his two legitimate children by his two wives.

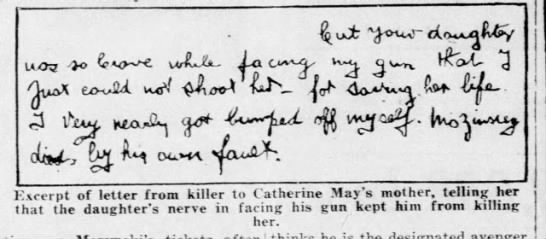

Anna stood trial in November 1907. If you’re going to be accused of murder, it helps enormously if your victim has been publicly revealed to be a consummate stinker. And then, of course, there was the “unwritten law.” In those pre-feminism days, when a woman reacted to her lover’s betrayal by pumping him full of lead, many saw this as simply taking a stand in favor of Noble Womanhood. Despite the open-and-shut nature of the case, the prosecution had good reason to be nervous.

Anna’s attorneys gave a plea of temporary insanity. In short, they argued that being involved with the likes of Arthur Brown would drive any woman crazy. Anna herself gave tearful testimony about the cruelty, the neglect, the emotional abuse Brown had heaped upon her. She had sacrificed so much for him, only to be repaid with heartbreak and broken promises. (The defense also hinted that Brown had performed an abortion on her.)

The jurors were wowed by her performance. Some of them wept.

|

| "Washington Post," November 20, 1907. This is typical of the sort of prose inspired by the trial. |

An attorney friend of Brown’s, Maurice Kaighn, testified that Brown had, in writing, admitted to being the father of Anna’s children. He added that he believed Brown’s refusal to marry Mrs. Bradley had indeed left her mentally unbalanced. The defense read some of Brown’s many letters to the court. In them, he repeatedly assured her that they would wed...one of these days. A parade of Anna’s friends and relatives gave testimony about her delicate mental state in the days leading up to the murder, adding that “eccentricity” ran in her family. An “expert on nervous diseases” stated that Anna had been suffering from “puerperal insanity” at the time of the shooting.

The prosecution’s case was much less baroque. They stated that Anna was not insane when she shot Brown, just angry as hell. It was, they said, a premeditated murder. She had followed Brown to Washington to spy on him, and when she discovered proof of his infidelity, she decided he had to die. They produced a witness who said that a few months before the murder, Anna had said that if Brown didn’t marry her, she would kill him. (During a previous fight, it was revealed, our damsel in distress had knocked her lover’s teeth out.) The prosecution also argued that just because Brown was a louse, that didn’t give Anna the right to send him to his grave.

Essentially, the trial was a contest between rational argument and melodramatic sentiment. Guess which side won. Yes, on December 2, the jury voted for acquittal.

Anna returned to Salt Lake City, only to find that old friends were leery of being around a woman who got away with murder. She and her children attempted to have Brown’s will overturned, without success. Anna lived in poverty and obscurity until her death in 1950.

The last public footnote to this case was in 1915, when Arthur Brown Bradley murdered Anna’s legitimate son Matt. He stabbed his half-brother to death over an argument over who would have to wash the dishes. (The coroner's jury--perhaps influenced by Bradley's youth--ruled that the killing was accidental.)

One is tempted to call him a chip off the old block.