|

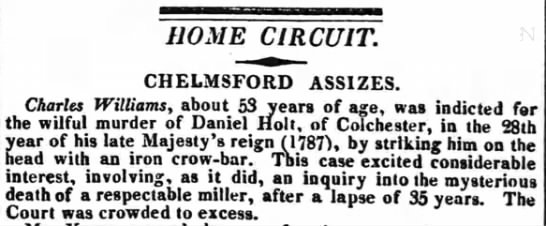

| "Morning Post," March 17, 1823, via Newspapers.com |

Sometimes, people voluntarily confess to having committed heinous crimes; usually due to a bad conscience and a desire to make some amends. However, some confessions are fake. These are generally the result of genuine delusions, a perverse form of masochism, or just a desire to create a sick hoax.

There are, more rarely, instances when an admission of guilt does not do a damn thing to solve a mystery because it's impossible to tell if the person spoke the truth. This week's tale deals with one of those cases.

Our story opens in Colchester, England. On the morning of January 4, 1788, a miller named Daniel Holt left his home to go work...and never returned. His concerned family and friends reported his disappearance to the local authorities, and a search was made throughout the district, but no sign of him could be found. Holt's whereabouts remained a mystery until two weeks later, when a man fishing in the River Colne came across a body which was subsequently identified as the missing man. Holt's corpse had some injuries to the head, but doctors were unable to say if they were inflicted before death, or during the time the body lay in the river. Lacking any other possible signs of foul play, the inquest ruled that the miller's death was accidental, and the sad matter was soon forgotten by everyone other than his grieving loved ones.

Life went on. And on. And on. Nearly three decades went by, with no hint that the death of Daniel Holt would ever be of any interest to anyone again. Then one night, a man named Charles Williams was sitting in a Colchester tavern with an old friend, William Leicester. As the two men shared some porter, Williams got to talking. Out of nowhere, he asked Leicester if he remembered "old Mr. Holt who had been found dead in the river all those years ago."

Leicester did not. There were few people left who did. Williams informed his friend that Holt had been killed at a pub called the Blue Pig. What's more, Williams and one Roger Munsey had been his murderers. One night in 1788, Holt, after drinking his fill, went outside to sleep it off on the steps of the home of a Mr. Smythies, which adjoined the pub. Around midnight, Munsey hit the sleeping man over the head with a crowbar, killing him. He and Williams then put the body in a sack and hid it in the cellar of the Blue Pig. They then cleaned up the blood as best they could. He did not say what they did with the body after that, or even why they committed such a horrid deed.

Williams begged Leicester to keep this ghastly little story to himself. Leicester did his best to keep his promise of secrecy, but, understandably enough, Williams' words preyed on his mind. After brooding on the matter for a few years, Leicester finally confided what he had heard to his wife, as well as a Mr. Hill. Inevitably, the local rumor mill got hold of the tale. Colchester began buzzing that they had a murderer in their midst.

Williams, rather unwisely, responded to this unpleasant gossip by going to the authorities. He made an official complaint to the Town Clerk's Office, accusing Leicester of slandering him. Williams asked that a summons be brought against Leicester, so that he, Williams, could formally clear his name. When Leicester was questioned by the justices, he said that he had not been responsible for spreading the rumors about Williams. He added that he would never have said anything about Williams' confession if he had not been brought before the court.

In March 1823, Williams was arrested on suspicion of murder and hauled before a judge and jury. Now that the issue of Holt's long-ago death had been revived, everyone was determined to finally get to the bottom of the matter.

This laudable goal proved to be sadly elusive. Aside from this alleged confession--which the defendant was denying he had ever made--there was little to suggest Holt had been murdered, by Williams or anyone else. Nearly everyone involved in the original investigation into Holt's death were themselves long in their graves. The only living witness to the inquiry was a sixty-four year old man named Edward Ladbroke. He testified that thirty-five years ago, Holt's body had indeed been found in a river about three miles from the Blue Pig. He himself had seen doctors examine the corpse. Ladbroke recalled that other than "two bloody specks" on Holt's skull bone, there were no visible injuries to the body.

Another prosecution witness was a woman named Elizabeth Buckingham, whose parents had owned the Blue Pig in 1788. She recalled that on the night Holt disappeared, she saw him in the pub in the company of "two bad women." The trio stayed until about ten p.m., and then left together. Buckingham saw them go in the direction of the river, which was about a mile away. She also stated that she knew Williams, and was positive he was not in the Blue Pig that evening. The cellar door of the pub was kept locked at night, so she was equally sure that it would be impossible for a body to be concealed there without anyone noticing. There was never any trace of blood found anywhere near the pub. One John Storrix corroborated Buckingham's testimony. He recalled seeing Holt and the two women in the Blue Pig on that fateful night. He did not see Williams, whom he had known all his life.

By this point, the judge decided that this trial was proving to be a big fat waste of time. He stopped the proceedings cold, telling the jurors that going by the testimony they had heard, it would be impossible to convict the defendant. Besides, if the surgeons who had examined Holt's body found no evidence the man had been murdered, how could this court hope to prove otherwise, over three decades later?

The judge sighed that the circumstances surrounding Williams' supposed confession made little sense. He could not imagine any reason why the defendant would make such a statement while casually chatting with an old friend, after keeping his alleged secret for so long.

Accordingly, Williams was acquitted and released from custody. We know nothing of his subsequent life, but I imagine he got quite a bit of side-eye from his neighbors.

Did Williams truly make this confession, or was he being defamed in a bizarre and unaccountable manner? Was Daniel Holt's death accident, or murder?

We'll never know, will we?

I suspect that, for whatever reason, Williams had told a tall tale, relating the 'murder' to Leicester and then telling him to keep it to himself. I think he was probably pulling a leg, in a drunken sort of way; why, I couldn't fathom.

ReplyDelete