|

| Kennewick Courier, September 5, 1913, via Newspapers.com |

Whenever children unaccountably disappeared in the 19th and early 20th centuries, it was common for people to instantly suspect they were kidnapped by "gypsies." These suppositions were generally proven false, to the extent that stories about such alleged abductions are now thought of as vintage "urban myths."

However, on at least one occasion, this conjecture was apparently proven to be correct. And the case only got weirder from there.

Our story opens on October 21, 1896, in the small northern New York town of Sissonville. At around six p.m., a seven-year-old boy named Frederick Brosseau was seen playing on a bridge near the lumber mill where his father John Brosseau worked. The boy often waited there in the evenings to meet his dad and walk home with him. That was the last time anyone saw Frederick. Almost immediately, the entire community turned out to look for the child. The mill was shut down and carefully examined. The local river was dragged and the surrounding countryside diligently searched. Not a trace of little Frederick could be found anywhere. The frustrated townspeople could only assume that the boy had drowned, and his body had become lodged on the river bottom.

The years passed by, with the tragic mystery becoming nearly forgotten by everyone except the Brosseau family. Then, in August 1913, the puzzle of Frederick's disappearance appeared to be resolved, and in an entirely startling way. On a boat traveling along the Ottawa River, a young man approached one of his fellow passengers, a Catholic priest. He explained that many years before, when he was a small child, he had been abducted by gypsies, who had treated him with great brutality. He stated that the gypsy caravan had taken him through a number of foreign countries, as they spent each winter abroad. Worse still, the gypsies had stolen a number of other children. The boys were used as virtual slaves, and the girls were sold for large amounts of cash. He had just now managed to escape from his captors. The caravan was still in Canada, with one kidnapped child, a girl, still in their possession. All the youth could remember about himself was that although the gypsies insisted on calling him "Patrick," he knew his real name was Frederick, and he had come from someplace in northern New York. The priest, convinced the young man was telling the truth, brought him to a Trappist monastery in Oka, a village in Quebec.

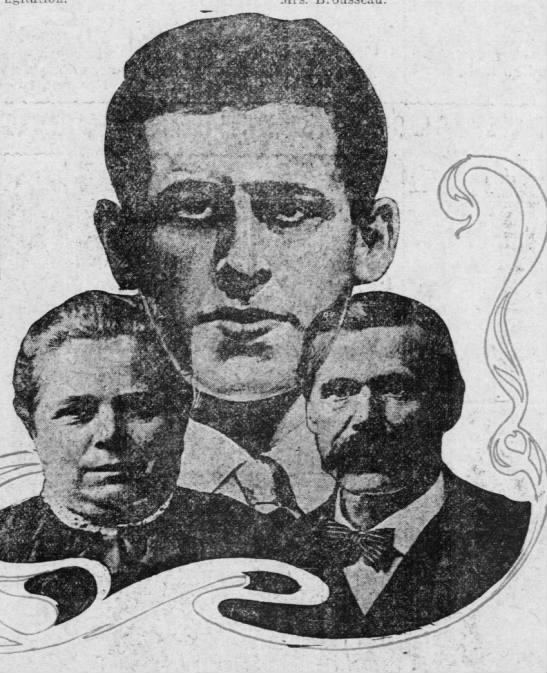

In an effort to discover the stranger's true identity, the little information he was able to provide about himself was broadcast in the local news media, along with his photo. The monks contacted a Father Marron, who lived in northern New York. Perhaps he would have some clues suggesting who the young man really was. By a remarkable coincidence, one Kate Perry, a sister of Frederick Brosseau's mother, lived in Montreal, and saw the newspaper articles about the mystery man. She was intrigued enough to visit the Oka monastery, carrying with her a photograph of Frederick taken shortly before he disappeared. When she compared the photo to the as-yet-unidentified young man, she became convinced he was her long-missing nephew. She immediately shared her astonishing news with the Brosseaus. Mr. and Mrs. Brosseau, along with one of their other sons, Frank, and Father Marron, immediately headed for Oka. Upon their arrival, the parents immediately recognized the stranger as their son. It was established that the young man had the same distinctive birthmark on his arm that Frederick had had. Plus, he so resembled Frank Brosseau that the two could have passed as twins.

The Canadian police immediately went in search of this caravan of kidnappers. The authorities were forced to instruct the newly-discovered Frederick Brosseau to remain on the monastery grounds, as he would be a crucial material witness when the gypsies were caught and put on trial. His parents had no choice but to return home without their long-lost son, but at least they now had the assurance that before long, they would be reunited for good.

|

| Mr. and Mrs. Brosseau, and the man who claimed to be their son Frederick. Pittsburgh Press, September 21, 1913. |

Unfortunately, a new danger soon emerged. The widespread publicity given to the return of the long-missing boy ensured that his former captors also learned where he was. It was reported that the gypsies made a number of attempts to steal the young man from the monastery, but the monks managed to foil all their evil plans.

Or so they initially thought. Just days after his joyful meeting with his family, the newly-identified Frederick Brosseau vanished from sight once more. On August 22, 1913, he was seen in the monastery's courtyard, talking to a stranger. Frederick seemed worried and upset. A few minutes later, he was gone.

What had happened? It was presumed that the gypsies had somehow threatened or coerced him into returning to their custody, but no one could say for certain why the young man made a second disappearance. Soon after "Frederick" vanished from the monastery, someone matching his description was seen boarding a train from New York, in the company of a woman claiming to be his mother. Was this the missing man? No one could say.

Was this enigmatic youth even the real Frederick? The Montreal Chief of Police for one, was skeptical. He had information suggesting that the mysterious young man had, in reality, one "Patrick Saileure," a barber who had been living in Montreal for years. The Police Chief was convinced the man identified as Frederick was either delusional or a sick practical joker.

Who really was this man? Why did he vanish so suddenly and oddly? Was any of his bizarre story true? And if he was an impostor, what happened to the real Brosseau boy?

We'll never know the answers to any of those questions. Because this time, Frederick Brosseau never did come back.

How heart-breaking for the family... If he were not the long-lost Frederick, how do we explain the family resemblance?

ReplyDeleteHe could have known the story and description and thought he could scam his way into well off family?

ReplyDeleteThe Brosseaus were a poor family.

Delete