|

| Louisville Courier-Journal, September 10, 1892, via Newspapers.com |

From the time the concept of "mass media" was invented, it has been universally acknowledged that nothing sells like sex or death. Put the two together, and you've got a sure-fire public favorite.

So, naturally, when people started dropping dead in a Louisville brothel, local journalists thought they themselves had died and gone straight to heaven.

The establishment run by forty year old Emma Austin spent the night of September 8, 1892 in a quiet manner--or, at least as quiet as it is in such places. Besides Mrs. Austin, the occupants were her eleven year old son Lloyd, Austin’s laundress Rachel Jackson, Mrs. Jackson’s young daughter Lillie, and Austin’s star employee, young, beautiful Eugenia Sherrill. Some four or five men came to call. Mrs. Sherrill--before presumably entertaining visitors in more private fashion--played “Nearer My God to Thee” on the piano. Someone sent out for ice cream, which was enjoyed by everyone in the house. And so to bed.

The next morning, young Lloyd said he was not feeling well, but Mrs. Austin insisted he go to school anyway. She then made breakfast: batter cakes, cantaloupe, jam, and coffee. Mrs. Austin and Eugenia Sherrill were the only ones to partake of the meal.

The other residents would soon be thankful they had skipped breakfast. Almost immediately, the two women began feeling deathly ill, suffering from uncontrollable vomiting and diarrhea. A Mrs. Johnson, who was temporarily boarding in the house, heard their cries of agony and summoned a doctor. (As a side note, reporters later had a lot of fun publishing Mrs. Johnson’s insistent remarks that she had no idea--no, sir, no suspicion in the world--that she was rooming in a house of ill repute.)

At first, the physician, Dr. Brennan, presumed the women were suffering from nothing worse than a case of severe food poisoning--an ailment sadly common in pre-refrigeration summers--and gave them the medicine appropriate for such cases. However, Austin and Sherrill continued to deteriorate. Their eyes dilated, they were covered in a cold sweat, and, most alarming of all, they had begun vomiting blood. The doctor soon realized the women had been poisoned, probably deliberately.

This shocking development opened up an embarrassing can of worms for everyone involved. As I said above, Mrs. Johnson was left trying to explain why she, a seemingly respectable lady, had spent the last two weeks living in a brothel. Eugenia Sherrill’s position was even more mortifying: prostitution was merely her secret side career. Up until now, she was known to society only as a member of one of Kentucky’s most prominent and respectable families. Even worse, for the past year she had been married to Edward Sherrill, a prosperous traveling salesman. In her agony, poor Mrs. Sherrill was frantic to be brought to her home so she could die without her double life being discovered. Unfortunately, she was far too ill to be moved. Dr. Brennan was helpless to save them. Eugenia died at 12: 45 p.m. Mrs. Austin’s sufferings ended two hours later.

|

| The Twice-A-Week Messenger, September 15, 1892 |

As it was obvious that foul play had taken place, the coroner immediately arranged an inquest. To save time, it was held in the brothel, which may be some sort of true-crime first. Because little Lloyd Austin was sick after eating the ice cream the night before, it was at first suspected that the dessert might have been poisoned. However, this theory was dismissed when it was realized that no one else felt ill after eating it. Most likely, the boy had just consumed so much of it he gave himself indigestion.

|

| Louisville Courier-Journal, September 10, 1892 |

Among the inquest witnesses was Mrs. Austin’s adult daughter, Nellie Koch. Mrs. Koch lived elsewhere, having, as she enigmatically put it, “left my mother’s house several weeks ago.” When she heard of her mother’s illness, she came to see her. She testified that Mrs. Austin told her that she and Mrs. Sherrill became sick right after eating breakfast. Mrs. Koch also revealed that she had done a fine job of eliminating evidence by throwing away all the remnants of the batter cakes. None of the other witnesses were able to contribute anything useful to the investigation.

An autopsy was performed on Mrs. Austin. (Since Mrs. Sherrill had obviously died of the same cause, it was evidently felt that it was unnecessary to perform a post-mortem on her.) It revealed that she had died from ingesting some irritant poison, possibly arsenic. As no such substance was kept in the house, this indicated deliberate poisoning. Considering that the two dead women were the only ones to eat the batter cakes, that meal was clearly what had been adulterated.

Meanwhile, Edward Sherrill returned to Louisville from a business trip, to be greeted by the shock of his life. It is hard to know what stunned him most: the news that his young bride had been poisoned, or the revelation that whenever he was out of town, Eugenia was spending her nights in a brothel. The despairing man dashed to Mrs. Austin’s house--where the bodies of the two victims were on macabre public display--and clasped his wife’s body in his arms, wailing piteously that he refused to believe the “vile stories.” It was some fifteen minutes before the hysterical Mr. Sherrill could be parted from the corpse, still crying and insisting that his beloved “Genie” had been “true to him.”

It must have been a heartrending thing to watch. And, of course, every detail was lovingly preserved in the newspapers.

Mrs. Austin was quietly buried in Cave Hill Cemetery. In contrast, Eugenia’s funeral in her native Meade County was one of the largest in the area’s history. Hundreds attended her burial, all of them apparently drawn by an odd combination of pity and salacious curiosity.

There was no question that the two women had been deliberately poisoned, but no one could agree on who did it, and why. Nellie Koch suggested that Emma deliberately poisoned her food, and for some unfathomable reason, decided to take Mrs. Sherrill with her. Mrs. Johnson endorsed this theory. She said she found it odd that as the women were dying, Mrs. Sherrill was frantic to survive, while, in contrast, Mrs. Austin seemed utterly indifferent to her fate. In addition, Mrs. Austin had recently visited the Jeffersonville penitentiary to see her brother, Sam Gore. (He was serving a ten year sentence for murder.) A guard had heard her telling Gore that she would soon “end her trouble.” It was also noted that Emma had recently heavily insured her life, making her son the beneficiary. And why did she insist on sending Lloyd to school without breakfast, even though he wasn’t feeling well?

Others suggested that the victims were poisoned by one of the brothel’s clients--possibly someone who had a motive to cover up his visits to the house. Two of the men who came by on the night before the poisonings spent the night, which would have made it easy for them to slip something unpleasant into the food before they left. After this theory was aired in the newspapers, it inspired half the males in town to visit the police stations, nervously denying that they had ever so much as laid eyes on Mrs. Austin’s establishment. Thus providing Louisville’s wives with a handy guide to which of their husbands had a taste for bordellos.

No first-class murder mystery is complete without nutty anonymous letters to the authorities, and this one was no exception. On September 12, the coroner received an unsigned letter which took the investigation into a whole new territory:

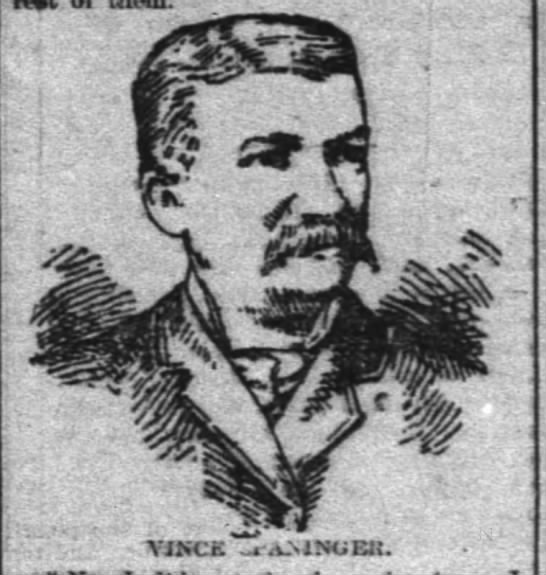

Dr. Berry: That poison Was intended For Vince Spaninger And Mrs. Austin. He Ate His Meals Thair, And He Has Bin Keeping A Woman for Twenty years. She Lives at 117 West Walnut, And Tha All Had A Fight And it Has not A more than. And she said she would Kill Him is She Caught Him in The Austin House. Enclosed You will find some of the Drug That Was used. Now find out who used it, Spaninger’s Wife or Mrs. Cole or Nelly Koch. Nelly and Her mother had the fuss about Him. The only Regret is that the Poisoning of The Innocent One. It is No secret About the way Spaninger And the Austin woman lived. All Second street know it. Policeman Sweeney Can Tell you if you Want to Know if He will talk.Vince Spaninger was a Louisville produce merchant. Mrs. Austin’s brothel was located directly above his store. It was far from the first time this anonymous author had written about Spaninger’s doings. For Vince, peddling vegetables was merely a way to make a living. His real profession was women. His romantic history was enough to make Casanova blush. For the past ten years or so, this same anonymous writer had been sending Speninger’s unfortunate wife Lizzie letters chronicling her husband’s many, many infidelities in great--and, it turned out--extremely accurate detail.

Anney Myers,

Betty Harper,

John Snyder,

Jake Dehl.

It is to be hoped you will Find the Guilty one.

|

| Louisville Courier-Journal, September 15, 1892 |

“Policeman Sweeney”--whose real name was actually “Feeny”--was asked about the anonymous writer’s claims, and he did indeed talk. He was able to confirm that Spaninger was one of the two men who had stayed overnight at Mrs. Austin’s house. It also emerged that Spaninger had suggested Emma make batter cakes for breakfast, but he declined to stay to eat any of them.

The plot, as they say, thickened.

Spaninger’s lady friend at 117 West Walnut turned out to be forty year old Josephine Cole. Like Mrs. Austin, Cole was a madam, but on a more modest scale. She made the bulk of her income from giving psychic readings at fifty cents a pop. She readily told reporters that yes, indeed, she had been Vince Spaninger’s mistress for the past fifteen years, and furthermore, she had tried to keep him from marrying. (By this point, Lizzie Spaninger was probably wishing Mrs. Cole had succeeded.) She admitted that she had been jealous of Vince’s relationship with the late Mrs. Austin, and confirmed that he had been the cause of the falling-out between Emma and Nellie Koch. She professed to have no idea who had written all those anonymous letters chronicling Mr. Spaninger’s every sordid move, but she intimated that whoever had deserved a medal. When questioned about the letters, Spaninger himself denounced them as a pack of lies. He had no idea who had poisoned Mrs. Austin and Mrs. Sherrill, but he did not believe Emma had committed suicide.

Nellie Koch denied that she had argued with her mother, and suggested that the letter writer--whoever he/she was--must also be the murderer.

The four names at the end of the anonymous letter were questioned, with little success. Betty Harper, a former prostitute, claimed not to have even known Mrs. Austin, and she certainly had no idea who had poisoned her. Annie Myers said much the same. John Snyder and Jacob Diehl were business partners of Spaninger’s. They both claimed to share the same convenient ignorance of the fact that a house of assignation had been operating over their store. However, Diehl was able to provide the interesting information that Spaninger believed that he thought all those pesky anonymous letters were written by Josephine Cole.

The “drug” the anonymous writer had included with the letter turned out to be arsenic. Did the writer get the arsenic elsewhere, or was it from the stash used as a murder weapon?

On September 14, two detectives called on Josephine Cole. They thought it was time to have a nice long chat. While there, one of them noticed that the writing on a photo of Spaninger resembled that of the anonymous tattletale. When he asked if this was her writing, Mrs. Cole realized the game was up and it was time to confess all. Yes, she had written those letters to Mrs. Spaninger. Most of them, at least. Some, she claimed, were sent by yet another of Vince’s mistresses, one Maggie Faulkner.

The detectives then asked the obvious follow-up question: where did she get the arsenic included with the letter? Mrs. Cole replied that on the morning Mrs. Austin cooked her last breakfast, Spaninger came to her house in an obviously agitated state. He told her that Mrs. Austin and Mrs. Sherrill were both going to die. When he took a handkerchief out of his pocket, he failed to notice that a brown paper packet fell out. Mrs. Cole presumed it was a love letter to another woman, so she managed to hide it with her foot until he left. When she opened the packet, she realized it contained poison. Mrs. Cole explained that she would have kept Vince’s little secret, if not for the fact that she subsequently learned that he had been far more than neighbors to Mrs. Austin. Although one would think the Casanova of the Produce Aisle’s habits would have been old news to Mrs. Cole, she was enraged enough to send that informative letter to the coroner, along with a sample of the powder and a list of names she thought could also dish the dirt on Spaninger. She believed his motive for the murder was to get Mrs. Austin out of the way so he could spend more time with his latest amour, Nellie Koch. (As a side note, Mrs. Cole was evidently unaware that her daughter Carrie was also said to have been Spaninger's mistress.)

As a result of this little tale, both Spaninger and Mrs. Cole found themselves under arrest. Spaninger denied every word of Mrs. Cole’s story; in fact, he was positive she was the poisoner.

And what of Nellie Koch, who, thanks to Mrs. Cole, was suddenly under scrutiny? She had bitterly quarreled with her soon-to-be-deceased mother. She had thrown away the breakfast before it could be analyzed. And she had, shall we say, a colorful past. In 1886, she married a railroad worker named Gilbert Brockman. The pair spent their brief married life getting kicked out of various residences thanks to Nellie’s reputation for “immorality.” And then there was the time Brockman--at his wife’s urging--tried to murder one of her former lovers. In 1887, Brockman suddenly fell ill and died. The smart money assumed Nellie had poisoned him, but his doctors stubbornly stated that Brockman died of natural causes.

This was beginning to look like one of those Agatha Christie stories where all the characters have a motive. Usually, there is a hard time finding suspects in a murder case. 1892 Louisville was just lousy with them.

When the inquest resumed on September 16, it, like the earlier such inquiry, did little to clarify matters. Vince Spaninger denied any involvement with the crime. He claimed that he would have stayed to share the fatal breakfast, if it had not been for the fact that he had important matters to attend to. When Nellie Koch was on the stand, she was asked why she threw out the breakfast leftovers, considering their obvious possible link to the sudden illness of the two women. She replied that it didn’t occur to her that her mother might be poisoned. She denied having any sort of romantic relationship with Spaninger. Dr. Brennan testified that Mrs. Austin’s stomach had indeed contained arsenic. And so the coroner’s jury delivered the inevitable verdict: the two women had been poisoned by a person unknown.

There was a brief trial of Spaninger and Josephine Cole, which was no more illuminating than the inquest. Everyone who had spoken at the inquest repeated their stories. Mrs. Johnson (whose real name turned out to be “Lydia Anderson”) had fled town to avoid testifying at the inquest, but authorities managed to haul her back to take the stand. She proved to be as unhelpful as all the other witnesses. Her testimony indicated that Nellie Koch was far from grief-stricken by her mother’s untimely end, and that Spaninger was in the habit of discreetly using Mrs. Austin’s window, rather than the staircase, to enter her room.

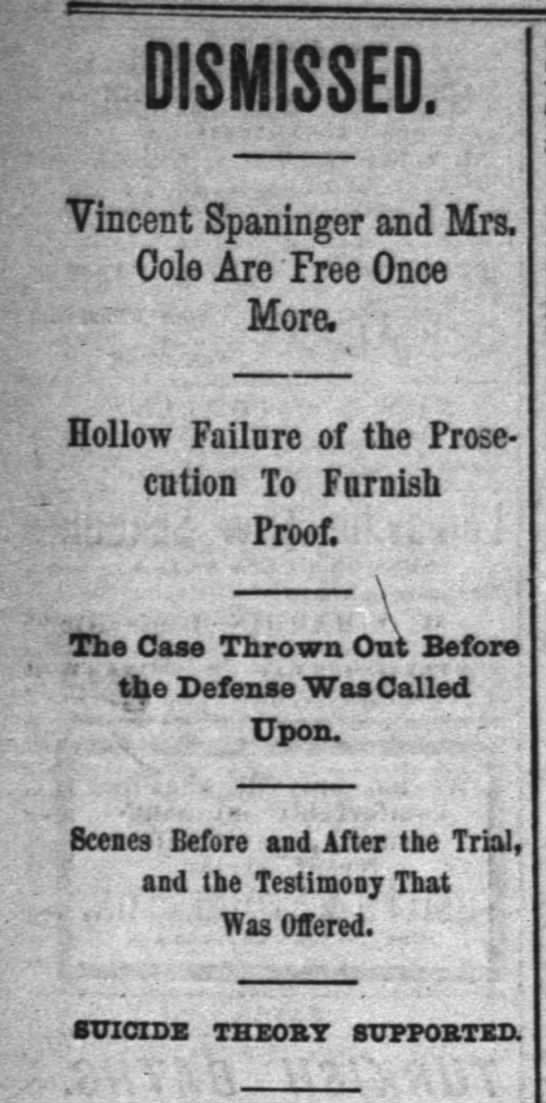

At the end of the proceedings, the judge could only sigh, “We have a world of evidence, without a scintilla of proof.” Enough dirty laundry had been produced to fill a million washing machines, but none of it was the slightest help with establishing who had poisoned Mrs. Austin’s batter cakes. Everyone involved was set free to carry on their curious lives, and this complicated little murder mystery faded from public memory.

|

| Louisville Courier-Journal, September 22, 1892 |

Although many people had motive for the poisoning, only two of them had an evident opportunity. No poison was found in any of the ingredients used to make the batter cakes. Thus, it was reasoned, the arsenic had to have been added to the batter itself. And the only people known to have been in the vicinity when the batter was made were Emma Austin and Vince Spaninger.

Was this murder/suicide? Did Mrs. Austin, resentful of Spaninger’s likely attentions to the younger, prettier Mrs. Sherrill, decide to poison her rival and herself? Or did Spaninger--certainly a man with a lot to hide--have his own secret motives to be rid of the women? Or did someone else manage to sneak in to poison the batter unseen?

Theorize away.

it could have been the coffee of the jam.

ReplyDeleteThat did occur to me (especially since coffee would mask the taste better than the cakes.) However, all the newspaper reports make it clear the cakes were believed to be the source of the poison, so perhaps others had some coffee and/or jam.

DeleteI wish the contemporary accounts made it clearer who ate or drank what that morning.

I'm confused about Mrs. Johnson and Mrs. Jackson. Which was the laundress, and which was the boarder who was embarrassed?

ReplyDeleteAck. Sorry for the typos. I just corrected them.

DeleteI'd bet on Spaninger, but of course, I have no proof. This case begged for a famous detective to be passing through town at the time.

ReplyDelete