|

| "New York Daily News," November 25, 1956, via Newspapers.com |

There are a number of tragic cases where people lose all memory of who they are, and, for whatever reason, no one is able to help them recover their identities. However, few such stories are as complicated and uncanny as the long, long search for the real “Charles Jamison.”

One day in February 1945, an ambulance arrived at the emergency entrance of Boston’s U.S. Public Health Service Hospital. Inside was an unconscious, middle-aged man whose condition was so obviously grave that the nurse on duty dispensed with the usual formalities and had him immediately admitted. She asked the ambulance driver for the man’s name.

“Charles Jamison,” he replied. The man would not or could not say anything more about the patient. Then he disappeared, along with the ambulance, never to be heard from again.

For some time, it was uncertain that “Jamison” would survive. He suffered from an acute stage of osteomyelitis (an infection of the bone marrow.) He had hideous sores all over his body, and his back was badly scarred with what doctors guessed were shrapnel wounds. After weeks of treatment, his life was finally out of danger. However, the infection left him permanently paralyzed from the waist down, and his speech was so impaired that anything he said was almost unintelligible. On top of all this, Jamison was suffering from complete amnesia. He was unable to say who he was, or what had happened to him.

At first, authorities assumed they could trace his identity. Surely, there had to be some record somewhere of this terribly ravaged man. But the more they tried to investigate the patient’s past, the more mysterious he became. The shabby clothes he had worn contained no identification of any sort, and they even lacked labels or laundry marks. No one ever called the hospital to ask about him. Inquiries to every ambulance service in and around Boston revealed that none of them had dispatched an ambulance to the Public Health Service Hospital on the day Jamison had been admitted.

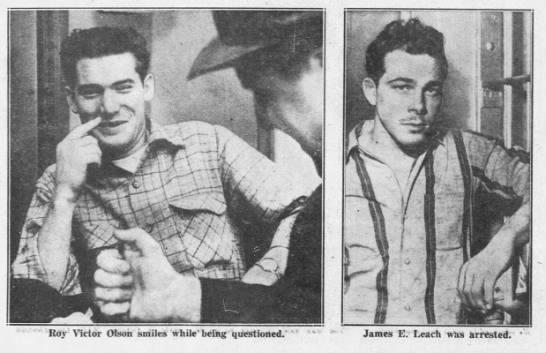

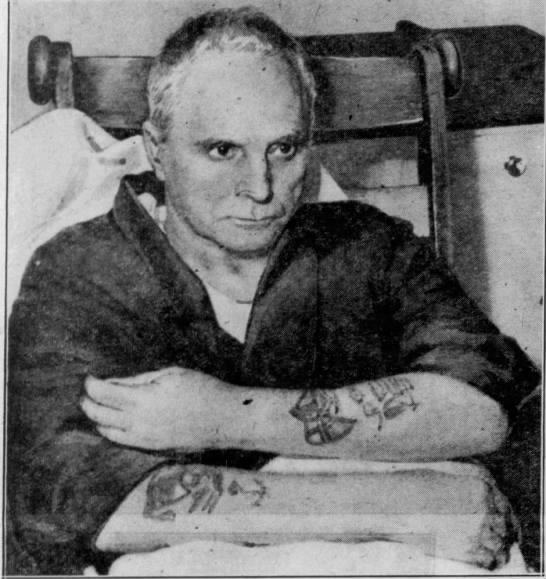

Jamison was around sixty years old, with graying hair and brown eyes. He was six feet tall and weighed about 200 pounds. There was a two-inch scar on his right cheek, the index finger of his left hand was missing, and both arms were covered with tattoos. His appearance was so distinctive that it was thought it might help identify him, but that failed to be the case.

The tattoos were a mixture of flags and hearts. Some of the flags were American, others British. One faded tattoo had a scroll that seemed to say “U.S. Navy.” This led to the assumption that Jamison had been a sailor in the naval and/or merchant service, a belief bolstered by the fact that he had been brought to the only hospital in Boston that specifically treated seamen. There was a theory that Jamison had been aboard a freighter that had been shelled and torpedoed by a German submarine, but that could never be verified. However, after being sent Jamison’s fingerprints, both the FBI and the military replied that they had no record of him, which would not have been the case had he served in either the Navy or the merchant marine. His photo was sent to missing persons bureaus across the country, but that proved to be just as futile as every other effort to identify him.

For years, the poor man spent long days sitting in his wheelchair in a blank silence. He rarely made any sounds, and seemed to take little notice of the world around him. Then, in 1953, the hospital’s newly-installed medical director, Oliver C. Williams, became intrigued by this most enigmatic of patients. He felt there had to be some way to learn who this man really was.

Dr. Williams decided the only way to learn Jamison’s identity was by finding a way to communicate with the man himself. He devised a simple word game, where Jamison would be given a phrase or simple question, and asked what, if anything, it meant to him.

When asked how old he was, Jamison stubbornly insisted that he was 49, although it was clear that he was far older. “How old is your wife?” made his eyes briefly light up, but after struggling to think for a moment, he sighed and said, “I don’t know.” He knew who Benjamin Disraeli and William Gladstone were, although he spoke of them as though they were still living British statesmen, not historical figures dead for many decades.

This communication method elicited information in a very slow and difficult manner, but Dr. Williams managed to learn enough to convince him that Jamison was an Englishman who had served in the British Navy. At one point, while looking at pictures of various parts of England, Jamison suddenly remarked “I’m from London!” Unfortunately, all he could add to that was the statement that he lived in “a gray house.”

Jamison said he had no living relatives, and that he had gone to sea at the age of 13. He recalled that he had attended the gunnery school at Osborne in 1891 or 1892. When he was shown an issue of “Jayne’s Fighting Ships,” he recognized the British battleship Bellerophon. It was commissioned in 1909, and took part in World War I. “I served on her when she was new,” he commented with evident pride. When asked what ships he had served on during the Great War, he was reluctant to reply. He said, “They were all in convoy, under secret orders. They had no names, only numbers, and if I knew them I couldn’t tell you.” Even when it was pointed out to him that the war was long over, he refused to give any more information on his wartime duties.

The little information Jamison provided about his career was sent to British naval authorities. However, they found no record that anyone named “Charles Jamison” had attended the gunnery school, or served in their navy. The British were equally unable to find any record of his fingerprints. More dead ends.

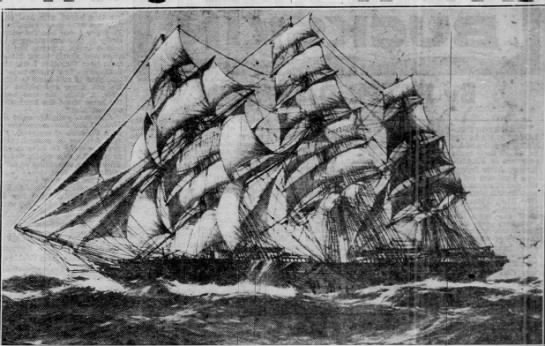

At this point, Jamison was able to provide one more clue. He told Dr. Williams that one of the tattoos on his arms was the British ensign crossed over a U.S. shield, with the motto “United.” The other was of an English clipper he had sailed on called the “Cutty Sark.” When contacted about the ship, London authorities confirmed that there had indeed been a clipper by that name...but it had been retired almost fifty years earlier, and no other ship had carried that name since.

|

| The "Cutty Sark" |

Then, the Jamison mystery took an even weirder turn. The name “Charles William Jamison” was found on the manifest of a U.S. Navy troop transport ship which had docked in Boston on February 9, 1945. This was just two days before Jamison had arrived at the hospital.

The manifest’s information about Jamison was all handwritten in ink--an inexplicable detail in an otherwise typewritten document. It claimed that he had been repatriated after spending four years in a German POW camp. He was picked up by the transport ship on January 24, in Southampton, England. His age was given as 49, and his birthplace was Boston.

The manifest also said that he had been a sailor on a ship which had been torpedoed. The name of the ship was “Cutty Sark.” Which had not been on the seas for five decades.

Records showed that no Charles William Jamison had been born in Boston between 1885 and 1905. No one by that name had been made a naturalized citizen. No one connected with the transport ship had ever heard of anyone by the name of “Charles William Jamison,” and they could not say who had made the handwritten notations about him.

Jamison was quickly becoming the spookiest amnesiac on record.

Authorities in Invercargill, New Zealand cabled the hospital that Jamison’s description sounded identical to that of a crew member of the freighter “Hinemoa” named James Jennings. As it happened, Jamison had mentioned the ship a few times. He remembered that at one time, he had been a mate on the Hinemoa. It had carried nitrates from Chile to England until it was sunk by the Germans. However, the name “James Jennings” rang no bells with him. Research proved that Jamison’s information about the Hinemoa was correct, but the freighter’s crew lists did not have Jamison’s name, or anyone matching his description.

It was discovered that a Charles William Jamison had been born in Illinois in 1908. His name appeared in the Coast Guard’s file of merchant mariners, but no further information could be found about him. When asked about this man, Jamison replied with only a blank stare.

In 1956, a segment dealing with the Jamison riddle aired on national TV. A viewer in Texas thought Jamison resembled his father-in-law, Frank J. Higgins. Higgins had been a chief engineer in the merchant service before he disappeared many years back.

As seemed to happen at every turn in the case, this fresh lead just led to more mystery. Higgins, who was born at approximately the same time as Jamison, was a New Yorker who spent his adult life as a sailor. On December 9, 1941, his ship, a freighter named the “Frances Salman,” docked in Galveston, Texas. It was in port for less than a week before it sailed for Portland, Maine with a load of sulphur. On January 12, 1942, Higgins’ wife Rosalie received a letter from him. He was at St. John’s, Newfoundland, about to sail to Corner Brook, Newfoundland.

Higgins and his freighter were never seen again. The Frances Salman failed to arrive at Corner Brook, and its fate is unknown to this day. In the words of the ship’s owners, “She simply disappeared from the face of the earth.” Although we’ll likely never know what became of Frank Higgins, we can at least rule out the possibility that he was “Charles Jamison.” Their fingerprints didn’t match.

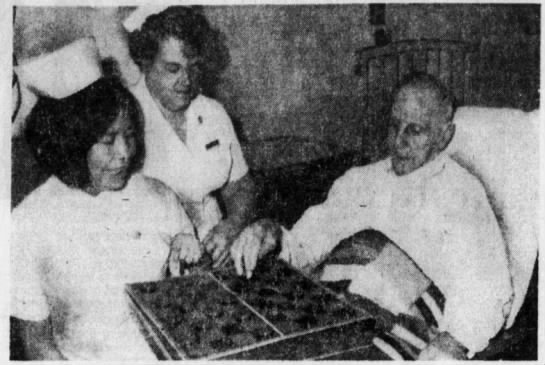

Thus ended the search for the true identity of Charles William Jamison. He died in the same hospital in January of 1975, still unable to say who he was, where he came from, or how he wound up at PHS. He was, in the words of a fellow patient, “the living unknown soldier.”

|

| Jamison playing checkers in 1973. "Dayton Daily News," January 21, 1975, via Newspapers.com |