|

| Neenah "News Record," April 23, 1935, via Newspapers.com |

“Giving it all up for love” is probably the most shopworn of melodramatic clichés. However, like all clichés, such things are to be found in real life, as well. One notable example is found in the life of one man who went from prosperous upper-class respectability to sad, squalid death, all thanks to his infatuation with an alluring woman.

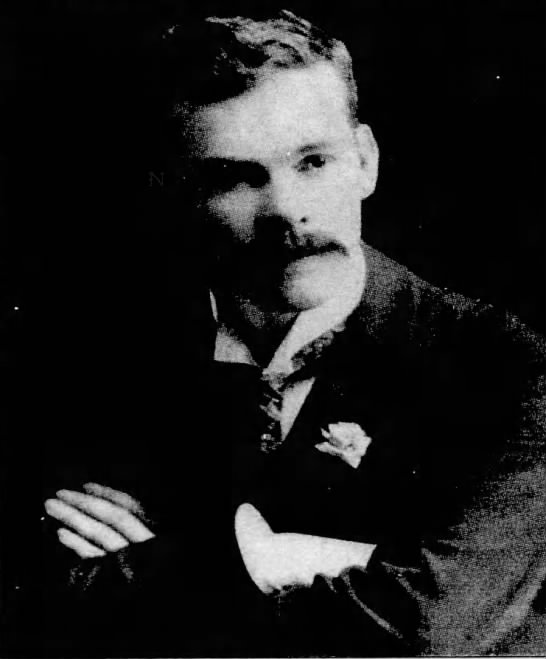

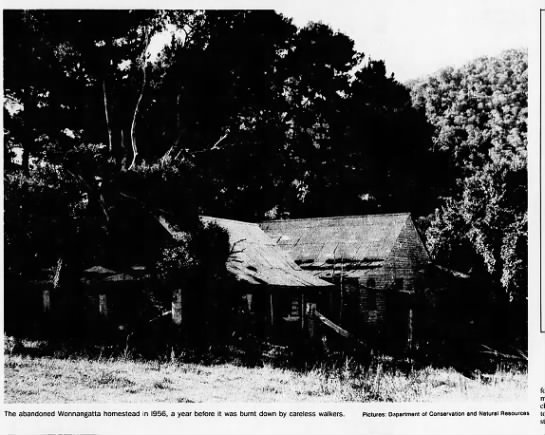

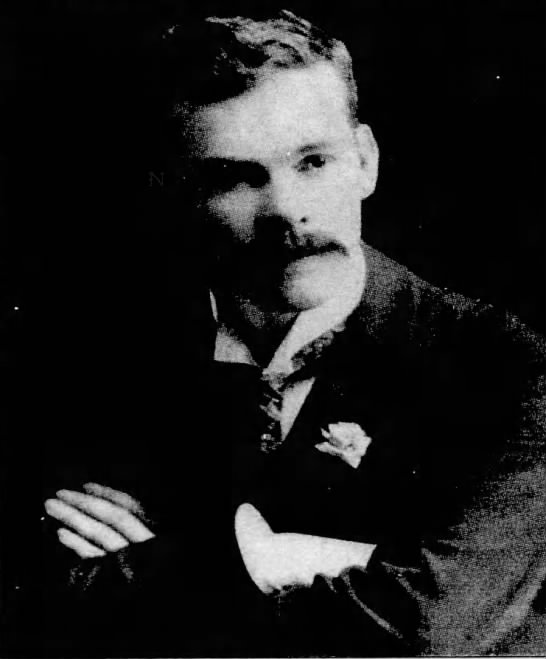

Francis Rattenbury was born in England in 1867. When he was 18, he apprenticed at an architectural firm. By 1892, he decided that Canada had greater opportunities for a talented and ambitious young man, so he relocated to Vancouver, where he was an almost immediate success. When Victoria was planning a new provincial legislature, a contest was held to pick an architect. Rattenbury’s bold, striking style won, ensuring that he would become one of Canada’s most influential building designers.

Rattenbury could be said to have practically built the city of Victoria. He was a brilliant architect whose work, such as the Parliament Buildings, the Empress Hotel, and his own home (now Glenlyon Norfolk School) still adorn the area. He was also prominent as a town planner, businessman, politician and philanthropist. He was not popular personally--he had a reputation for being ruthless, tight-fisted, and not overly scrupulous--but no one questioned his ability or his successes.

|

| Rattenbury at the height of his fame. The "Victoria Times Colonist," June 18, 2000 |

In 1898, the now renowned architect married a young woman named Florence Nunn. Everyone who knew Rattenbury thought it was an odd match. Francis was a handsome, dynamic sort who thrived on mingling in society and getting ahead. Florence was just the opposite. Of humble background, she was quiet, dowdy, and retiring. She rarely left their grand house, and had no taste for the elegant entertainments her husband enjoyed.

|

| Florence and their daughter Mary. The "Victoria Times Colonist," June 18, 2000 |

Inevitably, the two began leading separate lives. Although they continued to live under the same roof, by the time WWI dawned, relations between the Rattenburys were so bad they rarely even spoke.

During this period, Rattenbury’s professional life was little better than his personal one. His style of architecture had gone out of fashion, and several disastrous investments left him nearly broke. Like so many people who fail to find happiness either at home or at work, he sought consolation in a bottle. He soon became constantly depressed, and nearly constantly drunk.

However, in 1923, it looked like his depleted fortunes would be revived. Victoria’s city leaders hired him to design a new amusement palace, which eventually was named the Crystal Gardens. To celebrate, a dinner was held in his honor at the Empress Hotel. After this event, he met another guest at the hotel, a pianist named Alma Pakenham, who was in Victoria as part of a concert tour. And with this meeting, Rattenbury’s life began to take its final, irreversible decline.

28-year-old Alma was a gifted musician, beautiful, vivacious, and seductive. In short, she was everything Rattenbury’s wife was not. Alma and Francis were immediately strongly attracted to each other, and were soon embarked on a very public affair.

|

| Alma at about the time she met Francis |

For some time now, Francis had disliked his wife. Now that he decided he wanted to marry another woman, he hated her. When Florence refused to give him a divorce, he treated her with a cold brutality that shocked and scandalized Victoria. When Florence declined to move out of their house, he responded by shutting off the utilities and moving out all the furniture. When even that did not make her budge, he essentially moved Alma into the residence, forcing his wife to live upstairs. Finally, the increasingly harassed Florence agreed to legally end their marriage.

For Francis, this was the classic Pyrrhic victory. His children (who loathed Alma) rejected him. Victoria society, disgusted by his cruelty towards a wife who had been guilty of nothing more than being dull, ostracized him. By 1929, the Rattenburys realized that regaining their former standing in Victoria was impossible, and they resolved to start anew in England. By the beginning of 1930, the pair had settled in Bournemouth, in a home named Villa Madeira. With them were their young son John, and Christopher, Alma’s child from a previous marriage.

|

| "New York Daily News," July 14, 1935 |

The move failed to solve their problems. Although she found some success as a songwriter, Alma, who was used to a glamorous, busy life, was out-of-place in a sleepy resort town. She was a heavy cocaine user, which led her to experience wild mood swings--from hyperactive to deep torpor. Francis was even unhappier. No one knew or cared that back in Canada, he had been Somebody. Bored and unfulfilled, he again retreated into drunkenness and deep depression. Looking at this pitiful figure, no one would ever have guessed that he was once a powerful and successful man.

Francis’ decay had an even more alarming aspect for Alma personally: he became impotent. Unsurprisingly, Alma--still reasonably young, attractive, and now sexually frustrated--took a lover. That alone would not have necessarily led to disaster. It was her choice of paramours that turned this merely drab story into Greek tragedy.

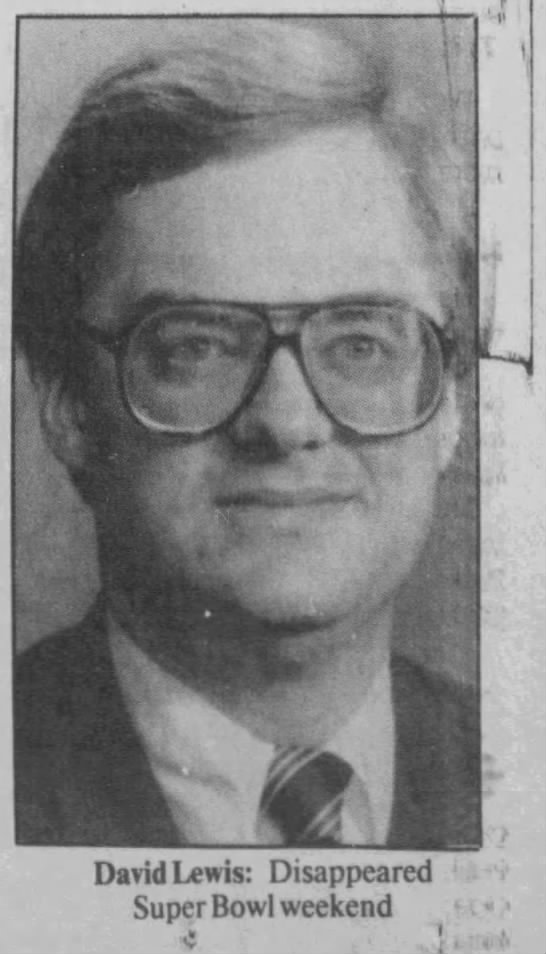

18-year-old George Percy Stoner worked for the Rattenburys as a chauffeur and general odd-job man. He was good-looking, shy, and, even for his young age, markedly naive and inexperienced. It is no wonder that when the much-older, sophisticated Alma seduced him, he quickly became completely under her spell. He was obsessed with her.

|

| "New York Daily News," July 14, 1935 |

Unfortunately, this obsession took a dark turn. Stoner became violently jealous of Alma’s husband. (Although it is unclear whether or not Francis was aware of his wife’s affair with their handyman, it seems probable that he was, and simply passively accepted the situation.) Although Alma assured her lover that she and Francis no longer slept together, he didn’t believe her. When Stoner learned that Alma and Francis were planning to go on an overnight trip, he interpreted that as the two renewing their physical relationship. He seethed over it, and nothing Alma could say eased his mind.

On the night of March 28, 1935, something dreadful happened in the Rattenbury home. Exactly who did what is fated to remain a mystery. All we know for certain is that at 10:30 p.m., Alma’s maid, Irene Riggs, phoned for doctors to come to the house immediately. The physicians found Francis sprawled on his chair, covered in blood. The stricken man, unconscious but still alive, was rushed to a hospital. And since the doctors immediately saw that he was injured as the result of a brutal attack, (later shown to have been by someone wielding a carpenter’s mallet,) the police were called in.

When officers arrived on the scene, the first thing they saw was Alma, very hysterical and very drunk. It was impossible to get a coherent story out of her, but under prolonged questioning, she finally blurted out that she had assaulted her husband. The next morning, a somewhat calmer Alma again asserted her guilt to the police. She said she and Francis had been playing cards when he told her he wanted to die, and begged her to kill him. She picked up the mallet, and, when she hesitated, her husband taunted her that she didn’t “have the guts to do it.” With that, she obliged Francis by bashing him over the head. However, Stoner told Irene Riggs that he was actually the guilty party. He couldn’t bear seeing Alma with another man, even if that man was her husband.

After Francis died of his injuries, his wife was arrested for murder. “That’s right,” Alma responded. “I did it deliberately and I’d do it again.” After Riggs told police what she knew, Stoner was charged as well. When he was arrested, Stoner repeated essentially the same story he told to Irene Riggs: after seeing Alma kiss her husband goodnight, he became so enraged that he crept in through the unlocked windows and hit Rattenbury--who was then dozing in his chair--with a mallet. Alma, he emphasized, was completely innocent.

Their trial was one of the most highly-publicized in Old Bailey history. Every day, the courtroom was crowded with journalists and the public, eager to hear every scandalous word. Alma, despite her original confession, pleaded “not guilty.” (She was persuaded to change her plea when it was pointed out to her that she would not want her sons to live with the taint of having their mother hanged for murder.) She made a good impression on the stand, giving her testimony with dignity and seeming credibility. Now her story was that when she went to her bedroom on the fatal night, Stoner came in. He seemed “a little queer.” When she asked, “What is the matter, darling?” He replied that he was in trouble, but could not tell her what it was. “Then he said I was not going to Bridport next day because he had hurt ‘Rats.’ It did not penetrate my head what he had said until I heard ‘Rats’ groan. Then my brain became alive. I jumped out of bed. I ran downstairs.”

Stoner--who also pleaded “not guilty”--did not take the stand. In his defense, it was suggested that the young man--who had, under Alma’s influence, also become a regular cocaine user--was simply not in his right mind at the time of the murder. His counsel argued that Stoner was guilty of nothing more than manslaughter--that although he had been in “an insane fit of jealousy,” he had not really intended to kill Francis.

It was obvious that if Alma did not beat Francis to death, her lover must have. It was up to the jury to decide which one was responsible. In the end, they chose to acquit Alma. Of murder, at least. The lurid details of the unconventional Rattenbury household had been laid bare for all the world to see. Even Alma’s own defense attorney condemned her morals, stating, “She will bear the brand of reprobation to her grave.” As Alma left the courtroom, the crowd outside booed her.

Stoner was found guilty, and sentenced to hang. When the judge asked him if he had anything to say, the young man said calmly, “Nothing at all, sir.” Stoner later told his father that as long as Alma was free, he cared little about his own fate.

Alma was shattered by the verdict. She was so distraught that it was felt necessary to place her in a nursing home. She constantly bewailed Stoner’s imminent end, and talked frequently of killing herself. Then, one night, she was visited by a woman whose identity remains unknown. What the two spoke about is equally mysterious. All we know is that this meeting probably led to what happened next.

The following morning, Alma borrowed money from a nurse. She used it to buy a knife. Later that day, she was seen on the bank of the River Avon. She was swinging her arms wildly, after which she fell into the river. When her body was recovered, it was found that she had not drowned. She had stabbed herself six times in the chest. She left behind a note saying, “If I thought it would help Stoner, I would stay on, but it has been pointed out all too vividly to me that I cannot help him. That is my death sentence.” She asked God to look after her children, adding, “Thank God for peace at last!”

When Stoner heard of Alma’s death, he broke down and sobbed. Then, he wrote to his attorney saying that he was now free to tell the truth about Francis’ murder.

Alma’s gruesome suicide created a change in public opinion. Alive, she was seen as the embodiment of wicked sexual passion, a heartless seductress who had led a poor boy astray. By killing herself in such a dramatic fashion, she became a tragic, even noble figure. There had always been much sympathy for Stoner, which now intensified. A campaign was launched to commute his death sentence, which ultimately proved successful. The Home Secretary announced that Stoner’s sentence would now be life imprisonment.

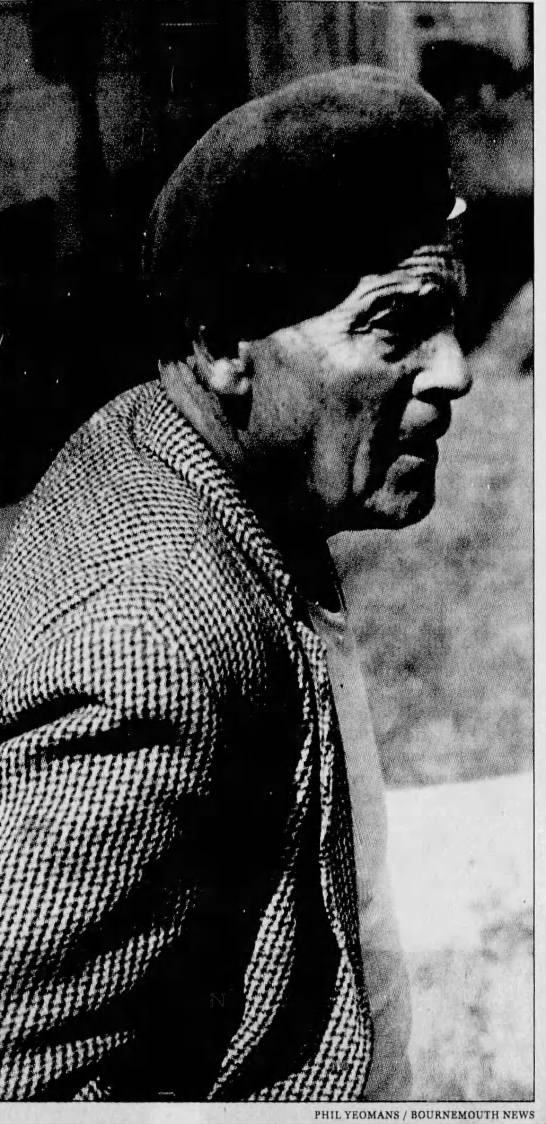

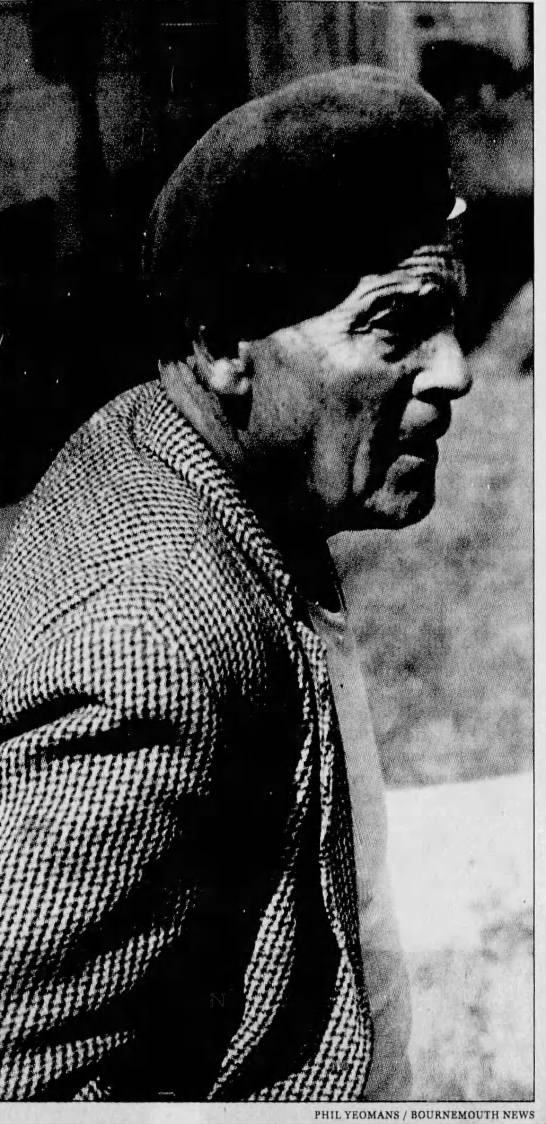

Stoner wound up serving only seven years. He fought bravely in World War II, (he took part in the D-Day invasion,) and subsequently married. He lived a quiet life until his death from Alzheimer’s in 2000. Eerily, he died on the 65th anniversary of Francis Rattenbury’s murder.

|

| Stoner in later life. The "National Post," November 30, 2002 |

George Stoner never spoke publicly about the murder. But in 2002, his wife of fifty years, Christine Stoner, gave an interview to Canada’s “National Post.” She described George as “a good father and husband. Nothing fazed him. He went the same gentle pace all the time.”

When asked if she thought her husband was guilty, she said quietly, “I think he was overcome by a moment of madness.” Christine added bitterly, “And this woman [Alma] really made a fuss of him and he pandered to her every demand.” When asked about the theory that George had taken the blame for Alma’s crime, Mrs. Stoner replied, “I’ve always thought that may be true, though I never broached the subject with my husband.”

Christine felt that her husband was forever haunted by what had happened. “Sometimes, he’d go very quiet and you’d see tears rolling down his cheeks. You just wanted to leave him alone and let him get over it. I didn’t like to keep on about it.”

At the time of the murder, many thought Stoner was indeed “covering up” for Alma. On the other hand, Alma’s former sister-in-law, a Mrs. Kingham, named Stoner as the murderer. According to her, Stoner overheard Rattenbury urging his wife to have an affair with a Bridport man named Jenks, in the hope that this would persuade Jenks to invest in one of Francis’ business projects. Stoner was so infuriated that Francis would urge Alma to essentially prostitute herself that he was driven into violence. The question of which of these star-crossed lovers actually did the brutal deed is fated to remain uncertain.

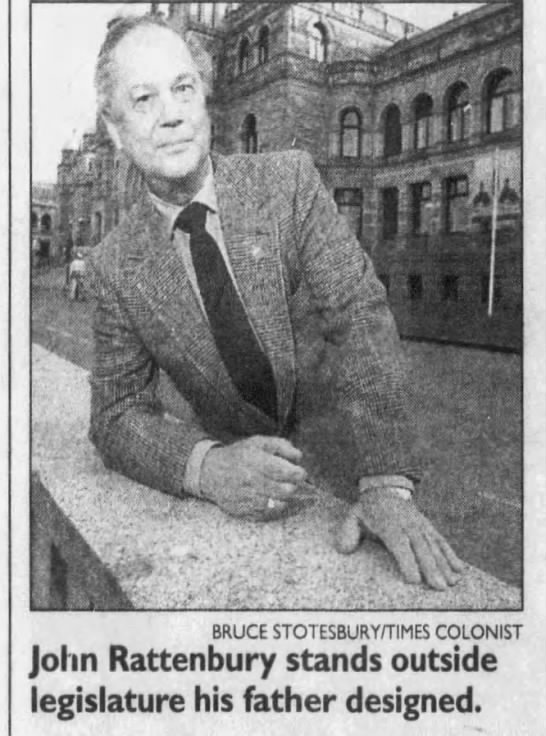

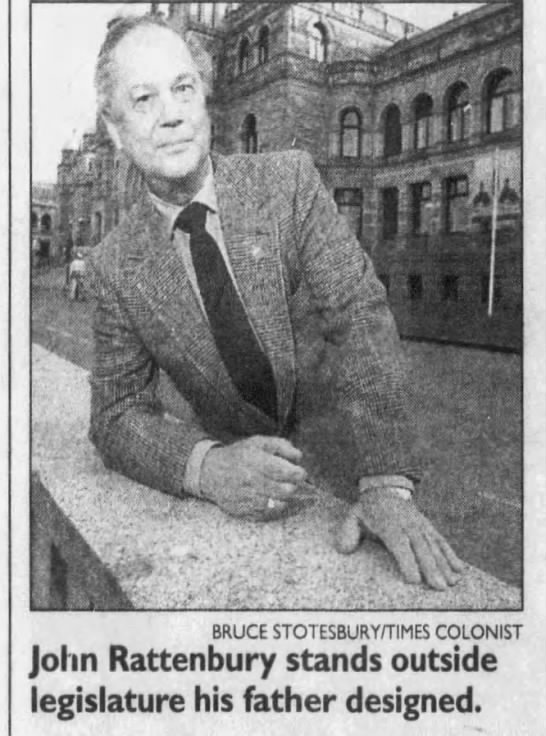

If there is anything positive to say about this grim tale, it is that Alma’s two sons managed to overcome their family tragedy and go on to lead happy and productive lives. John followed in his father’s footsteps and became a successful architect. In 1998, John Rattenbury was invited to Victoria to participate in the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the legislative building designed by his father. He was able to see Francis as not reviled, but honored. John later called it a “closing of a circle, and the highlight of my life.”

Time does indeed heal all things. Even the reputation of the once-disgraced Francis Rattenbury.

|

| Victoria "Times-Colonist," February 11, 1998 |