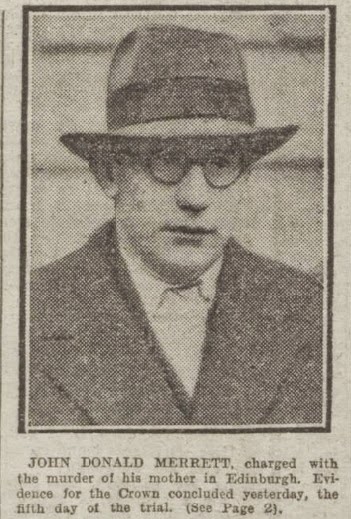

In Edinburgh in the year 1926, Mrs. Bertha Merrett lived in a West End flat with her seventeen-year-old son, John Donald. Her husband, an electrical engineer named John Alfred Merrett, was a bit of a mystery. The couple married in New Zealand about twenty years before. They subsequently moved to St. Petersburg. The Russian climate was deemed too harsh for their son, so Mrs. Merrett took little John to Switzerland, leaving her husband behind. Not long afterward, World War I broke out, and John Alfred disappeared from sight. After the war, Mrs. Merrett and son returned to New Zealand, but as far as we know, her husband was never heard from again. Bertha's story was that he was killed during the chaos of the Russian Revolution, although rumor had it that Mr. Merrett was alive and well and living in India, leaving open the possibility that Mrs. Merrett was merely giving out a genteel cover story for a failed marriage. In any case, in 1924, she brought her son to Britain to finish his education. She had ambitions for her only child to enter into the diplomatic service. As a stint at Malvern College had not worked well for John, largely because of his wayward conduct, Mrs. Merrett enrolled him in Edinburgh College, a non-resident institution. She rented nearby housing for the both of them, to ensure he would remain under a mother's watchful eye.

Bertha Merrett, we are told, was charming, upright, cultured, and clever, well-liked and admired by everyone who knew her. Although her son would, once he reached his majority, inherit a substantial sum from his late grandfather, Mrs. Merrett's own income was limited, but she managed her funds with typical self-discipline and sense.

Like many single parents of only children, her whole life revolved around her son, who was her pride and joy. She had reasons for this doting affection. Young John was physically mature for his age, well-mannered, and highly intelligent. Unfortunately, she was blinded to the fact that he was also spoiled, selfish, lazy, and shockingly callous and self-indulgent. It was the classic case of the adoring parent happily oblivious to the fact that she had raised a sociopathic little monster.

Although Mrs. Merrett believed her son was attending classes at the University every week day, John was actually doing no such thing. His real occupation was slipping out every night to attend the local nightclubs (he was romancing a "dance hostess" named Betty Christie,) and venturing out every day to get an education of a more unconventional sort on the seamier streets of Edinburgh. After his first month or so at the University, he ceased to attend classes at all. His mother, of course, continued to stretch her scanty income to pay his school fees.

There was another major secret John was hiding from his mother. For some weeks, he had been supplementing the small allowance she gave him by embezzling from her. He had stolen one of her checkbooks, and by forging her checks and letters to her banks, he had set up a complicated system of withdrawing funds from her accounts, while using other forged checks to make bogus deposits to them, so that--for the moment, at least--Mrs. Merrett was unaware that there was money missing.

This juggling act could not last forever, of course. By March 1926, both her accounts were nearly drained dry. Bertha Merrett's discovery of her son's fraud was not only inevitable, but imminent.

On the morning of March 17, the Merrett housekeeper, Henrietta Sutherland, arrived for work. All seemed normal. Mrs. Merrett was her usual cheerful, courteous self. She and John had just finished breakfast, so the maid first went to clear the table. By the time she finished and returned to the sitting- room, Mrs. Merrett was writing letters at a small table. Young John was sitting opposite his mother, reading. Mrs. Sutherland went into the kitchen.

Just a few minutes after the maid had entered the kitchen, she was startled to hear a pistol-shot, followed by a scream and a thud. Transfixed by shock, she stood still, unsure how to process what she had just heard. Before she could pull herself together enough to investigate, John rushed into the kitchen, exclaiming that his mother had just shot herself. When Mrs. Sutherland gasped her astonishment at the news, the boy said something about how "he had been wasting his mother's money, and he thought she was worried about that."

When they re-entered the sitting-room, the maid saw Mrs. Merrett lying on her back, bleeding heavily from the head. She was unconscious, but still breathing. There was a pistol on the top of the bureau. Mrs. Sutherland had never seen it in the flat before. They called police, who soon arrived on the scene with an ambulance, and the stricken woman was rushed to the hospital.

John told police that he had been reading while his mother was answering her mail. Everything was peaceful until he suddenly heard a shot. When he looked up, he saw his mother fall to the floor. When he was asked why Mrs. Merrett would wish to kill herself, he shrugged and replied, "Just money matters."

The position of the pistol at the time Mrs. Merrett collapsed was, unbelievably, never positively determined. Mrs. Sutherland said she had seen it on the bureau, where, according to John, he had placed it after his mother shot herself. On the other hand, one of the two policemen who were first on the scene later said he had seen his colleague lift the gun from the floor near the injured woman. The other policeman said he could not recall if he had picked up the gun from the floor or the bureau.

After his mother was settled in her hospital room, young John attended to what was, for him, more pressing matters: He bought a motorcycle, and visited his girlfriend's dance hall to take her out for a ride. She later said that Merrett had casually told her that his mother had shot herself "with his own pistol" while the maid was in the kitchen. Later in the day, while talking to a friend, he repeated this story.

So far, the two witnesses, Merrett and the maid, were telling a bizarre story, but at least a consistent one. However, that very day, Mrs. Sutherland--for reasons that have boggled the minds of all students of this case--changed her testimony entirely. According to a CID investigator, she told him that she was in the kitchen when she heard a shot. She then came running into the sitting-room,

where she saw Mrs. Merrett fall from her chair, still clutching a pistol in her hand.

Unfortunately, the CID men were unaware at the time of her previous story, so they unquestioningly accepted this account. It was, they instantly decided, as clear a case of suicide as you could ever see.

They found a number of letters on Mrs. Merrett's desk, including two from one of her banks, informing her that her account was overdrawn. There was also a letter she had been in the middle of writing to a friend just at the moment when she was shot. It was a cheerful note, saying how she and her son were now comfortably settled in their flat. This letter was free of blood-stains.

One would think that it did not take a Hercule Poirot to think that there was something wrong with this scene. Surely one would think it odd that the lady would start to pen a breezy, happy note, and then suddenly interrupt it to grab a gun and shoot herself in the head, while miraculously getting no blood on the notepaper in front of her. But, no. The inspectors had decided it was a suicide, and they were damned if they would let any inconvenient facts spoil their nice, quick, tidy investigation. (Incidentally, when Mrs. Sutherland was later asked to explain the discrepancies in her accounts of the tragedy, she explained that she only claimed to have

seen Mrs. Merrett holding a pistol because "she was excited at the time." She went back to her original story, saying she had seen nothing. Investigators were content to leave it at that.)

Meanwhile, Mrs. Merrett lay in her hospital room--in the ward reserved for suicidal patients--in very grave condition. X-rays showed a bullet lodged at the base of her skull. Doctors decided it could not be removed. When she regained consciousness, she had no memory of what had happened. All she could say was that "I was sitting writing...when suddenly a bang went off in my head like a pistol." When a nurse asked if there had been a pistol there, Mrs. Merrett responded in astonishment, "No. Was there?" She added that while she was writing, John was "standing beside me, waiting to post the letter." She gave one of her doctors a similar story, adding that she told her son, "Go away, Donald, and don't annoy me." The next thing she heard was "a kind of explosion, and I don't remember anything more." It was, she added in bewilderment, "as if Donald had shot me."

For whatever reason--possibly because everyone assumed she was a would-be suicide--no one gave the poor perplexed woman any hint of why she was in the hospital. Doctors and visitors only told her that she had "a little accident." The Inspector in charge of the case, when told that Mrs. Merrett was dying, but still conscious and capable of speech, did not even bother to interview her.

As for her loving son, when told by a doctor that his mother was very ill, but still had "a fighting chance," John replied with obvious unease, "So it's still on the cards that she will recover?" He did not bother to inform her two sisters or any of her many friends of her grave condition.

Mrs. Merrett lingered in physical pain and mental unease until March 27, when she sank into a coma. On the morning of April 1, she died.

Mrs. Merrett's sister, a Mrs. Penn, flatly refused to accept the official verdict of suicide, although she naturally shrunk from accepting the only possible alternative. She chose to convince herself that her sister's death was due to some dreadful freak accident. Before she died, Mrs. Merrett had begged her sister to "look after Donald," and Mrs. Penn tried to do just that. She and her husband moved into the Merrett flat with her now-orphaned nephew. A few days later, Mr. Penn found an empty cartridge case a few feet from where Mrs. Merrett had been sitting at the time when she was shot, and he informed police.

When questioned about this discovery, John told police that he had bought the gun to serve as protection. A couple of weeks before the shooting, his mother took the gun from him and put it in her bureau, and that was the last he saw of it. He added that after his mother was shot, he picked up the pistol and placed it on the bureau.

Mr. and Mrs. Penn remained in the Merritt flat until the lease expired. Meanwhile, John went back to his double life: ostensibly attending classes, in reality haunting the local dance-halls. In June, the Penns returned to their home. John was, according to the terms of his mother's will, left in the care of a Public Trustee until he reached his majority and came into his inheritance. This guardian sent him to a country vicarage in Buckinghamshire. The plan was that he would study under a private tutor to prepare him for another attempt at University life.

It was only when this Trustee took over Mrs. Merrett's estate that her son's exploits in forgery and embezzlement were uncovered. It began to dawn upon the police that perhaps they had just been a wee bit hasty in dismissing the lady's death as an obvious suicide. The CID did their own experiments with ballistics and handwriting analyses, and the result was that an arrest warrant was issued for John Donald Merrett. He stood trial for murder and forgery in January 1927.

As you may have already guessed, the case against young John looked very grave. Mrs. Merrett's doctors and nurses also testified that they had not seen any gunshot residue around her wound, indicating that she had not been shot at close range.

However, John Merrett did have some things in his favor. The particular horror attached to the crime of matricide, coupled with the defendant's youth, led many to find it unbelievable that this suave, articulate young man could commit such an unspeakable act. One woman on the jury was heard to say during the trial that "I'm

so sorry for that poor boy!"

Merrett's counsel suggested that in the hospital, Mrs. Merrett was so mentally confused that she was simply unable to remember shooting herself. They made a great deal of the fact that the doctor who had autopsied Mrs. Merrett's corpse, and who was now testifying about the improbability that she had shot herself, originally called her injuries "consistent with suicide." They also emphasized the police's unbelievable negligence in not taking a dying deposition from Mrs. Merrett. If this had been done, the defense suggested, their client would never have been put on trial at all. With such contradictory and inconclusive evidence, they asserted, the jury had no choice but to rely on the presumption of innocence.

The jewel in the defense crown, however, was the testimony of Sir Bernard Spilsbury. Spilsbury was the most famous pathologist of his day. At the time of the Merrett trial, he had acquired such a reputation--albeit one not always deserved--of infallibility that juries inevitably accepted his views without question, no matter what evidence there might be to contradict him.

He told the jury that he believed Mrs. Merrett's wound was not inconsistent with suicide. The heavy bleeding might have washed away any gunshot residue from the entry wound. (Although under cross-examination, he had to admit that the position of the wound was an unusual one for a suicide.)

The defense had less success explaining away those forged checks. Also, doubts were raised whether Mrs. Merrett had ever seen the letters from her bank stating that she was overdrawn--the letters which were only later found on her desk and used by her son as a motive for her suicide. Only John Donald could have answered all the lingering unsolved questions surrounding his mother's death--and he declined to testify at his trial.

After deliberating less than an hour, the jury decided the defendant was guilty of forgery. As for the charge of murder, they delivered that peculiar Scottish verdict of "Not Proven." It was, as a local newspaper commented, "An unsatisfactory ending to a rather unsatisfactory case."

Merrett was sentenced to a year in jail. He served his time in an open prison, under far from unpleasant conditions. Upon his release, he was given a temporary home by a Mrs. Bonner, a friend of Bertha Merritt's who took pity on this unfortunate young man who was now alone in the world. Merrett's way of thanking her for this act of kindness was by eloping with his hostess' pretty seventeen-year-old daughter Vera. The young couple married in March 1928. Three months after the wedding, the newlyweds were arrested on a charge of obtaining goods by false pretenses. It seems that, feeling nostalgic for the good old days, Merrett opened a bank account under a false name and bought a large amount of goods from local tradesmen. As he had only deposited the sum of one pound in this account, the checks he have these merchants immediately bounced. Merrett soon found himself in a considerably less desirable prison, doing nine months with hard labor.

True-crime doyen William Roughead wrote of the Merrett case only a few years after John Donald's second conviction, and so his account ends there. Roughead was a lawyer, well aware of the laws of libel. As the subject of his essay was still alive, Roughead contented himself by commenting that the public had heard nothing more from Merrett, "but you never can tell: we may do so yet."

We did indeed, but that was not until 1954, two years after Roughead's death. After being released from prison the second time, Merrett claimed his grandfather's inheritance, settling part of it on Vera. He changed his name to "Ronald Chesney," and embarked on a full-time career of smuggling, theft, gun-running, drug-dealing, and many similarly sordid crimes. He spent more time in prison than out of it. After his money ran out, he began to cast covetous eyes on the share of his fortune that was in the possession of his wife. However, the two of them had been bitterly estranged for many years. (Vera, a Roman Catholic, refused to consider divorce.) The only way he would get that money back was if she predeceased him.

This inevitably led to certain trains of thought.

In January 1954, Merrett/Chesney was in Germany. He used a stolen passport to make an undetected return to England, where he snuck into the flat Vera shared with her mother and drowned his wife in the bathtub. While creeping away from the murder scene, he unexpectedly ran into his mother-in-law. From his point of view, there was nothing for it but to strangle the woman so he could make his getaway.

|

| Vera Merrett |

The elderly woman had bravely put up a lengthy fight for her life--scraps of flesh were found under her fingernails--and Merrett was spotted leaving the scene. This proved to be his final undoing. Merrett, on the lam in Germany, read the newspaper accounts of the double homicide--his arms still raw from where Mrs. Bonner had clawed him--and learned that he was wanted by the police. He knew that this time, there was no escaping the gallows.

Merrett had spent his entire life cheating everyone around him, so it was fitting that his last act was to cheat the hangman. Before the authorities could catch up with him, he had withdrawn into a lonely forest by the Rhine, where he put a pistol into his mouth and shot himself.

Roughead's prediction came true possibly even more horrifically than he had imagined.

.JPG)