The history of exploration is full of strange stories, but it is hard to think of any that have more elements of both tragedy and comic opera than the 19th century search for Timbuktu. This so-called "lost city" was that era's most intriguing prize. It was reputed to be a site of unparalleled richness lying waiting to be discovered in the heart of Africa. Tales were told of it being a place of unimaginable wealth, learning, and power--a sort of Atlantis on dry land.

There were, naturally, many efforts to find this magnificent hidden kingdom. And they only succeeded in finding The Weird.

The earliest known effort by a Westerner to discover the city was an American named John Ledyard. He had never been to Africa and knew not a word of Arabic, but that did not stop him from setting boldly out in 1788. He made it as far as Cairo, when, while ineptly treating himself for a "bilious complaint," he accidentally overdosed himself with sulphuric acid. He died almost immediately. He could not know it, but his expedition was to set the tone for all explorers following in his footsteps.

The next hunt for Timbuktu was led by an Irishman, Daniel Houghton, in 1791. All went well until he reached Gambia. He was attacked by bandits, who stole his supplies and beat him to death.

In 1795, a Scottish explorer named Mungo Park set off for Timbuktu, only to also be robbed along the way. He tried again in 1803 with a party of 46 men. Not one of them came back alive.

In 1817, a British surgeon named Joseph Ritchie (now mostly known--if he's known at all--as a friend of the poet Keats) tried his hand at finding Timbuktu. Ritchie had no experience whatsover as an explorer, and it showed. He spent the small sum allocated to him in mostly worthless ways--including having himself circumcised so he could pass himself off as an Arab. His party soon ran out of supplies, and he wound up dying of starvation embarrassingly quickly.

The growth of serious Timbuktu madness can be blamed on a now-obscure fabulist named James Jackson. In 1809 he published a book with the alluring title, "An Accurate and Interesting Account of Timbuktu, the Great Emporium of Central Africa." It may not have been accurate, but it was certainly interesting. It described a huge city boasting vast wealth and natural resources--it was literally paved with gold--a paradisaical climate, and, perhaps of greatest interest to Jackson's male readers, loads of beautiful, sexually adventurous women. His Timbuktu was sort of a cross between the Garden of Eden and the Playboy Mansion.

It's still not quite certain if Jackson was a deliberate fantasist or a deluded lunatic, but in any case, the book was a massive best-seller, going through at least ten editions. No one, it seems, questioned the scientific accuracy of the book, and the hunt for Timbuktu became an obsession throughout Europe.

The first major search for this glittering prize was a Venetian Egyptologist named Giovanni Belzoni, who set off in 1823. Before he had traveled more than ten miles, he died of dysentery.

In 1824, the British decided to give it another go. The responsibility for planning the expedition fell to Lord Henry Bathurst, the Secretary of State for Colonial Affairs. This was to prove to be an unfortunate choice. As Timbuktu was thought to lie about 500 miles inland from Africa's west coast, the logical thing to do would be to approach it from that direction.

Bathurst, however--for reasons no one has quite understood--opted to approach Timbuktu from the north. It did not seem to bother him that this meant crossing 3,000 miles of the Sahara Desert. He blithely assumed one could sail into Tripoli, rent a few camels, and just ride to one oasis after another until you reached Timbuktu. It was a thoroughly insane plan. One would have to be thoroughly insane to go through with it.

Enter Alexander Gordon Laing.

The thirty-year-old Laing was an officer in the Royal African Colonial Corps in Sierra Leone. He was handsome, idealistic, brave, energetic, dashing, adventurous, and highly ambitious.

Unfortunately, he was also a delusional egomaniac.

Laing, like nearly all seekers of Timbuktu, had no experience as an explorer. In fact, he had little experience in much of anything other than writing dreadful poems about himself. As for his capabilities as a military officer, his commander once wrote that "His military exploits are even worse than his poetry."

Nevertheless, he had from boyhood nursed dreams of making himself famous by "some important discovery." He felt he was the one destined to finally find the legendary Timbuktu. He wrote with his usual grandiloquence, "The world will forever remain in ignorance of the place, as I make no vainglorious assertion when I say that it will never be visited by Christian man after me...I am so wrapt in the success of this enterprise that I think of nothing else all day and dream of nothing else all night." When he learned of Bathurst's expedition, he immediately volunteered to lead the mission. Bathurst was favorably impressed by Laing's courage, poise, and willingness to make the trip on the cheap. The madcap young officer was hired on the spot.

Laing set off for Africa in 1825. He eventually made his way to Tripoli, where the British Consul, Hanmer Warrington, was to help him travel to the interior of the continent. However, the more Warrington saw of Laing, the more pessimistic he became about the would-be explorer's chances for success. The younger man's uncertain health, lack of money, and general air of fecklessness disturbed him.

Warrington became even more disturbed when his daughter Emma fell instantly in love with Laing. Before long, the young couple was begging him to allow them to marry. The idea of having this impecunious--and, he was now convinced, slightly cracked--would be explorer as a son-in-law horrified him, and he initially refused to even consider the idea. He wrote Bathurst, "Although I am aware that Major Laing is a very gentlemanly, honourable and good man still I must allow a more wild, enthusiastic and romantic attachment never before existed." Finally, when Emma threatened to kill herself if she was not allowed to marry Laing, Warrington relented--with one condition. He allowed them to go through with a marriage service, but the union was not to be consummated until Laing returned alive and well from his expedition.

Warrington evidently surmised that the chances of that happening were small.

The young lovers agreed to his terms, and they were wed in July 1825. Love gave a new impetus to Laing's ambitions. He was now seeking fame and fortune not just for himself, but for the lady of his heart. "I shall do more than has ever been done before," he vowed, "and shall show myself to be what I have ever considered myself, a man of enterprise and genius." Four days after the wedding, he began his trek across the Sahara, taking with him only a few camels and a small band of assistants.

Highly dangerous, uncharted territory, lack of any skilled planning, little outdoors experience, and a leader who was a real-life version of Monty Python's Black Knight. What could go wrong?

Everything, of course. Although we know very little about this expedition other than Laing's few surviving letters, it is clear that this was an enterprise doomed even before it began. The would-be conqueror's messages back to Tripoli consisted largely of poems (about himself, naturally) and paranoid attacks on his rival explorers, particularly one Hugh Clapperton, who was at that time conducting his own Timbuktu expedition. Although the two men did not know each other, Laing had become convinced that Clapperton was part of some sort of conspiracy against him. (As it happened, Clapperton--a far more experienced explorer--was himself resentful that the Colonial Office had commissioned a neophyte like Laing.) This sense of personal affront made Laing all the more obsessed with being the first to find the legendary land of Timbuktu.

In his letters, Laing repeatedly begged his reluctant father-in-law to send him a miniature of Emma. Otherwise, he added rather unnecessarily, "I might go mad." When he received the portrait, Laing was distraught. Emma, he thought, looked pale and unhappy. Was she ill? Pining for him? In a sudden panic, he wrote Warrington that he was immediately returning to Tripoli. The Consul, feeling himself unable to handle another dose of his lunatic son-in-law's society, quickly replied with reassuring words about Emma's good health and spirits.

As it happened, it was not Warrington that persuaded Laing to continue his journey, but a comet he saw in the sky. He saw it as a "happy omen" beckoning him on. He received further encouragement in the news that Clapperton's expedition was finding its own share of troubles. (Clapperton eventually died before reaching Timbuktu.)

Laing and his little party pressed on, undeterred by lack of food (at one point, Laing recorded that he had gone for an entire week without eating) and temperatures that soared as high as 120 degress Fahrenheit. Their small supply of drinking water was muddy and hot. Virtually all they had to eat were repulsive patties of dried fish soaked in camel milk. After five months of this slow torture, he reached an oasis in what is now Algeria. From there, Laing was certain, it was merely a short hop across the desert to his goal.

Unfortunately, at this stage in the journey, a new danger emerged. His planned route was dominated by tribesmen called the Tuareg, desert pirates who made a practice of preying on those foolhardy enough to travel through their domain. The local traders told Laing that it would be necessary for him to give a large bribe to the Tuaregs before they would allow him through. Even then, they advised, his safety was by no means assured. They strongly suggested that he just forget the whole thing.

Laing scoffed at such cautionary words. He was never one for taking anyone's advice, and besides, he was convinced he was a Man of Destiny. He refused to pay off the Tuaregs, and he certainly would not turn back now. In January of 1826, he resumed his journey. Within a couple of days, his caravan was attacked by the Tuaregs, who killed several of the party and took all their possessions. Laing himself was seriously wounded, with no one to help him except an injured driver and a couple of forlorn camels. Undeterred, he had the man strap him on one of his camels, and the nightmare trek went on. Laing wrote to Tripoli describing his injuries in harrowing detail. He had eight saber cuts on his head, "all fractures from which much bone has come away," a fractured jaw, a mutilated ear, a "dreadful gash" on the back of his neck, a musket ball through his hip, five saber cuts on his right arm which left three fingers broken, a broken left arm, and deep gashes on both legs. Oh, and he had caught the plague, as well.

Making his resemblance to the Black Knight complete, he seemed to shrug it all off as only a flesh wound. His main concern was that his beloved Emma would be turned off by his disfigured condition.

Never underestimate the power of blind obsession. Amazingly enough, this ill-equipped eccentric, now seriously broken in both body and mind, succeeded where so many other more experienced, more well-funded men had failed. On August 13, 1826, Laing entered the city of Timbuktu.

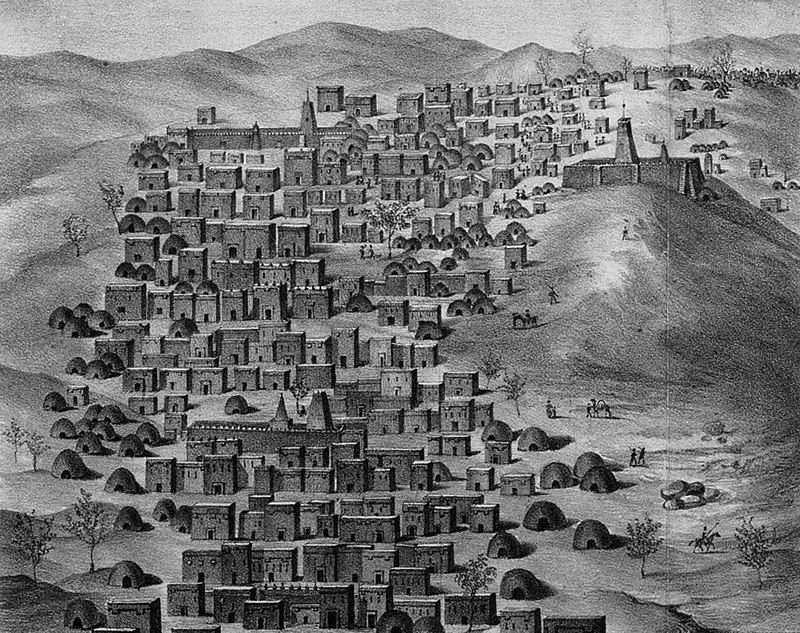

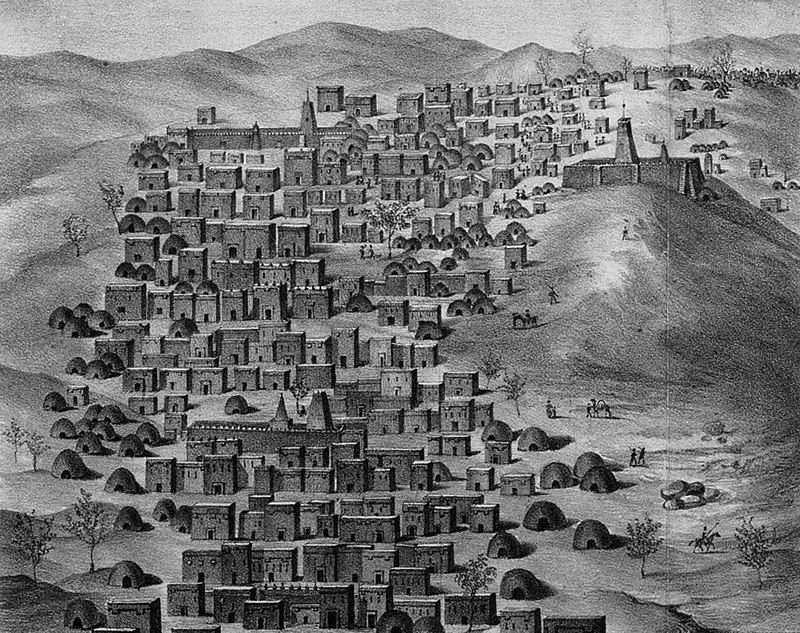

It must have been one of the greatest anticlimaxes in the history of exploration. A few centuries earlier, Timbuktu had indeed been a prosperous trading post and center of learning, but the town had long fallen into decay. Instead of the wealthy Valhalla Laing had been promised, he found a dreary little collection of mud brick buildings populated by largely impoverished villagers who were wondering what in the hell he was doing there.

|

| Timbuktu in 1830 |

This letdown, instead of forcing Laing to come to his senses, seems to have propelled him all the way over the edge. He cheerfully wrote that this "great capital...has completely met my expectations." He took to parading through the streets in full dress uniform, informing the understandably bemused populace that he was the emissary of the King of England.

He had informed Tripoli that he intended to travel to Sierra Leone, but for reasons unknown, he headed in the opposite direction. On or about September 25, 1826, he and a servant were attacked by Tuaregs. They strangled Laing to death, then cut off his head. His body was left in the desert to rot. The servant, who had only survived by pretending to be dead, made his way to Tripoli two years later, where he told the world of the tragedy. [Note: Some historians believe Laing was actually murdered by his guide, a supposedly "friendly" sheik who had volunteered to escort him through the desert. The theory is that the sheik feared that if Laing returned alive, he would expose the area's thriving slave trade and bring in other highly unwanted foreigners.]

Emma Warrington Laing was devastated by the news of her husband's gruesome death. Although her father pushed her into an early remarriage--to his vice consul--she never recovered from the shock, and spent the short remainder of her life suffering from ill health and depression. She joined her first husband in the grave in 1829, aged only twenty-eight.

It is a cruel irony that although Laing had succeeded in his goal of being the first European to reach Timbuktu, he has received little of the glory he so yearned for. Although he had kept a journal detailing his adventure, it was lost after his death. In 1828, a Frenchman named René Caillié managed to enter the city. While there, he confirmed what little was known of Laing's fate. On his return, he published a grandiose history of his travels which reached a wide audience. The French gleefully publicized his achievement, boasting mendaciously that it was a Frenchman "with his scanty personal resources alone" who had been the first to reach Timbuktu, not one of the hated British. As a result, Laing's feat was curiously overshadowed.

That undoubtedly would have pained him more than any saber wound.