As I’ve mentioned before, murder by poison can be some of the most difficult crimes to solve, for the simple reason that the murderer does not have to be anywhere near their victim in order to kill them. Seemingly random, motiveless slayings are usually equally baffling. Combine these two factors, and you may well see a mystery would leave Sherlock Holmes baffled. Such was the tragic situation that haunted Ohio State University in early 1925.

When the University’s students needed medicine, they went to the health service office, where a doctor would write a prescription to be filled at the College of Pharmacy’s dispensary. On January 29, a student named Timothy McCarthy, who was suffering from a bad cold, obtained a prescription for the standard remedy of the time--capsules filled with aspirin and quinine. However, the supposed cure just made him feel worse. Immediately after taking a capsule, he began suffering from terrible pain and cramps throughout his body. Fortunately, McCarthy had the sense not to take any more of the capsules, and after a few days of misery, recovered his usual good health.

|

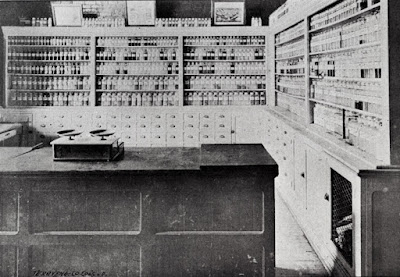

| The dispensary in the early 1900s. Via Ohio State University Archives |

On January 31, two other students with colds, Harold Gillig and Charles Huls, also took medication from the dispensary. Like McCarthy, both young men instantly fell gravely ill. Gillig pulled through, but Huls died while suffering violent convulsions. Campus doctors ruled that Huls died of tetanus.

|

| Charles Huls |

On February 1, yet another student, David Puskin, got cold medicine from the dispensary. Twenty minutes after taking a capsule, he was dead. The doctors decided the unfortunate young Mr. Puskin succumbed to meningitis, and placed all his friends in quarantine.

Two days after Puskin’s death, OSU student George Delbert Thompson took cold medicine he had received from the dispensary. He immediately fell so spectacularly ill that campus officials were finally forced to realize that something very weird was going on. An analysis of the contents of Thompson’s stomach revealed that he had swallowed strychnine. Campus doctors, sheepishly muttering that, after all, it would be easy to confuse the symptoms of meningitis or tetanus with those of strychnine poisoning, admitted that Huls and Puskin had also been poisoned. Four other students were sickened by the dispensary “cold medicine,” but fortunately, all survived. And it became obvious that strychnine could not have been added to the cold medicine by mistake: the poison was found in only a few capsules. In any case, strychnine could easily be differentiated from quinine. The University realized they had a serial poisoner on their hands, one who lived or worked in the campus, and the police were brought in.

The obvious suspicion was that the killer worked at the dispensary, but no one could understand how, even under those circumstances, he or she could have tampered with the capsules. All dispensary medications were made up under the close supervision of faculty members in the College of Pharmacy. The sixty-four students who had been working at the pharmacy just before the poisonings began were all questioned by police. Nearly all of them expressed utter bafflement at how the poison could have been added, considering how no prescription was filled without faculty looking on. The one exception was a young woman who admitted that she had filled the aspirin-and-quinine capsules so often over the last two years that she stopped bothering to bring in supervision when that prescription was made up. She pointed out that the bottles of quinine and aspirin were always stored together in the same place, so making a mistake with them was virtually impossible.

Chemical analysis of the remaining stock of cold medicine found that the majority of the capsules were harmless--except for one, which contained pure strychnine. This discovery proved it was impossible for the poison to have mixed in by accident.

Unsurprisingly, every student who still had cold medicine they had obtained from the dispensary wasted no time giving their capsules to investigators. Among them was one capsule which contained enough strychnine to kill someone four times over. Taking into consideration the number of students who had been sickened by the capsules, it was calculated that of the three hundred capsules that had been recently made, eight had contained poison.

The State Pharmacy Board looked at all recent legal sales of strychnine, and found nothing suspicious. On the night of February 4, Dr. Clair Dye, the dean of the College of Pharmacy, inspected the dispensary in hope of finding something that might shed light on the mystery. In the back of a shelf in the chemical storeroom, he found a small bottle of strychnine. However, it was nearly full and covered in dust, suggesting that it had sat there, forgotten, for some time. This potential clue turned out to be a red herring: the bottle had belonged to William Keyser, who belonged to the pharmacy’s faculty. He had on two occasions taken strychnine from the bottle to use in his classes.

For a while, it looked like a pharmacy student named Nelson Rosenberg was a promising suspect. He admitted to having bought strychnine tablets off-campus, as a stimulant to help him concentrate on his studies. (Yes, back in the good old days, many people took minute doses of strychnine and arsenic as a “health tonic,” and if you are thinking that this must have led to a lot of unpleasant unintended consequences, you are perfectly correct.) Rosenberg told police that a bottle of strychnine had been kept in a campus laboratory, easily accessible to anyone who had murder in mind. However, all the other students insisted that they had never seen such a bottle, and Rosenberg himself admitted that he had no idea what happened to it. All this emitted a very strong odor of fish, but Rosenberg must have somehow managed to persuade investigators that he was not a maniacal mass poisoner, because the police appear to have lost interest in him.

Another odd figure who emerged from the investigation was a 19 year old pharmacy student named Louis Fish. When questioned, Fish admitted that he had given David Puskin the killer capsule. He explained that he and Puskin had been friends, and when Puskin fell ill, he asked Fish to fill his prescription for him. He confessed that he had sneaked into the pharmacy “without authority,” in order to get the medicine. He had not told anyone about this before, as he had no wish to get mixed up with a murder investigation. Fish had been the first student to work in the dispensary the week the fatal capsules were circulated. Furthermore, on the night of January 30 Fish suddenly left campus to go to his home in Canton, 100 miles away. However, as soon as he arrived in Canton, he drove straight back to the University. When asked about this curious behavior, Fish could only say that “I didn’t want to stick around Canton.” Fish was put under arrest, only to be released the following day. Police presumably had some good reason to drop both Fish and Rosenberg from their investigation, but if they did, it was evidently never publicly recorded.

|

| "Atlanta Constitution," June 3, 1934, via Newspapers.com |

In July 1926, the Ohio State Board of Pharmacy released its report on the mystery, and it was one long salute to Captain Obvious: the poisonings were deliberate and the strychnine had been obtained off-campus. The End.

That was also The End of any official investigation. Not only do we not know who the killer was, we cannot even say why the poisonings were done. Did the evildoer intend to murder just one person, and distributed the other fatal capsules to hide who the real target was? Or was it a case of some secret psychopath getting their kicks by poisoning people at random? In either case, they got away with murder. Perhaps not for the first time. Or the last.

These poisonings seem frequently to start and stop abruptly. Maybe to pick up somewhere else...

ReplyDeleteWhat a weird story. What was the point?

ReplyDeleteSounds creepily close to the original "Tylenol poisonings !" Seems like any of the survivirs were incredibly lucky !

ReplyDeleteI'm surprised the parents and press didn't kick up a big fuss about this. You don't expect to send a child to college and have them murdered there.

ReplyDeleteIt sounds like someone was getting a thrill out of playing Russian roulette with other people's lives.

Charles Henry Huls was my paternal great-uncle. His father did eventually "kick up a big fuss," but the perpetrator was never found, and time has forgotten these men. I blog about it periodically at charleymyboy.blogspot.com.

Delete