|

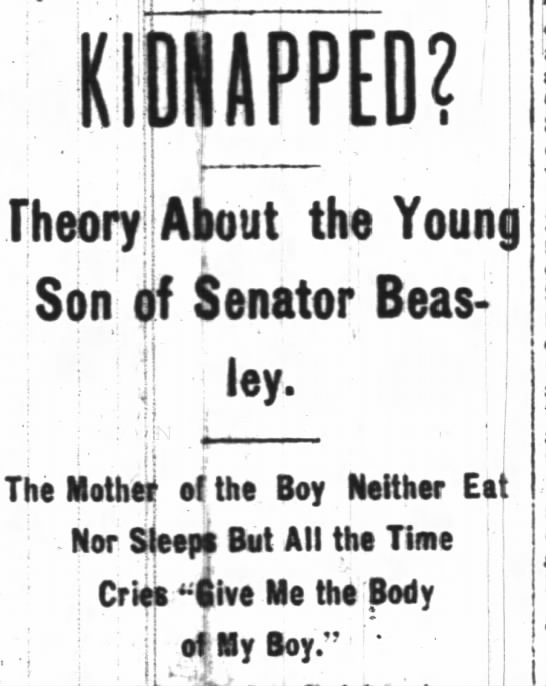

| Atlanta Constitution, February 17, 1905, via Newspapers.com |

A while back, I wrote about the tangled tale surrounding the disappearance, and presumed kidnapping, of a small boy named Melvin Horst. Although the following case is much more obscure, it has many striking similarities to the Horst mystery.

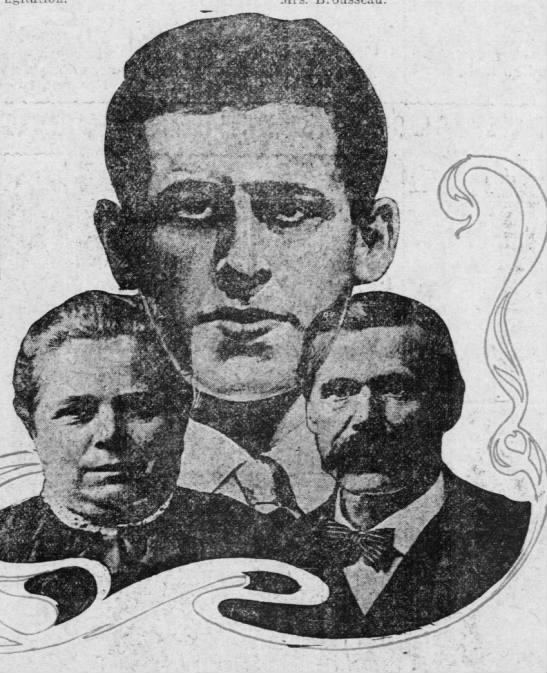

In 1905, a family named Beasley lived on a beautiful and prosperous farm just outside the small town of Poplar Branch, Currituck County, North Carolina. They were what used to be called “people of solid worth.” The head of the household, Samuel Beasley, was a state senator, and many believed he was destined for higher offices. His wife Carrie was admired as a kindly and accomplished woman. The couple had three children: seventeen-year-old Moran, eight-year-old Kenneth, and Ethel, who was four. Kenneth was a handsome, gentle boy who did well at school. Other children liked him, and adults loved him.

Although the Beasleys were admired and respected in their community, there was one glaring exception to their popularity: if you were to ask Joshua Harrison what he thought of Samuel Beasley, the answer would likely be completely unprintable. Harrison was a tall man in his fifties, with a formidable beard and a temper to match. He was such a hothead that in his younger days he had twice stood trial for murder, but in both instances he won an acquittal.

Harrison supplemented his farming income by selling homemade wine out of his barn. It was said to be very good wine, and, judging by the frequent rowdiness emanating from his unofficial tavern, very potent as well. Many of the locals disapproved of his enterprise, and foremost among them was the upright, sober, and politically powerful Samuel Beasley. In 1903, he got a bill passed through the state legislature outlawing the sale of wine in Currituck County.

Harrison, unsurprisingly, was not pleased. The following year, he happened to run into Beasley on the road between their farms, and made his wrath known in no uncertain terms.

“I hear that 1903 legislation was for me,” he scowled.

“If you heard that,” Beasley replied calmly, “you heard right; for you are the only person in Currituck creating a disturbance, and the people petitioned the legislature on the subject.”

“I’ll be damned if I don’t sell it in spite of ‘em,” Harrison retorted. “If I can’t sell it in gallons I’ll sell it in barrels, and the people can come and get it. When they stop me from selling it they’ll be God damned sorry for it.”

After this exchange, the two men avoided each other.

Life appeared to return to normal. On the morning of February 13, 1905, young Kenneth Beasley dressed, had breakfast, and began his walk to school. On his way out the door, he told his mother, “I’ve seen some mighty pretty puppies, and I want one.”

Little did she know those were the last words she would ever hear him say.

Kenneth’s day at school progressed in its usual uneventful fashion. By the time of the noon recess, the temperature had warmed enough for him to not bother donning his overcoat and gloves before going outside to play. At 1 pm, the school bell rang summoning students for the afternoon session. All the children returned to the classroom...except Kenneth.

Young Beasley’s cousin, Benny Walker, told the teacher that he had been playing with Kenneth when the bell rang. Instead of heading back to school, Kenneth had turned toward the woods behind them, saying, “I’m going back farther.” Benny did not see him after that.

The truancy of this normally well-behaved boy was deeply puzzling--even more so when the teacher saw that Kenneth’s coat and gloves were still in the cloakroom. If he had planned to run away, surely he would have taken them with him?

The schoolmaster sent another boy, Everett Wright, to go look for Kenneth. He returned with the news that Beasley was nowhere to be found. Then Benny Walker was dispatched to make a more thorough search. Walker scoured the woods, then made his way to a nearby store and asked the proprietor, a Mr. Woodhouse, if he had seen anything of the missing boy.

Woodhouse immediately realized something very strange was going on. He locked up his store and accompanied Walker back to the school, where he advised that school should be dismissed and a more comprehensive inspection made. The older boys were organized into search parties while Woodhouse went to gather neighbors. By four pm, one hundred and fifty people, all of them hunters familiar with the swampy timberland, were exploring the area. The search spread for miles, without one trace of Kenneth being found. The following morning, a telegram was sent to Samuel Beasley, who was attending the legislative session in Raleigh. He left for home at once.

By the next day, the search party had doubled in size. Hunting dogs were brought in, but the heavy rain and snow prevented them from picking up a trail. That night, a rumor emerged that a child had been heard crying for help from a lumberman’s cabin deep in the woods. This cabin was said to be inhabited by a mysterious recluse. However, when searchers arrived at the cabin, there was no sign of the hermit--or Kenneth.

On February 24, the “Raleigh News and Observer” printed a letter dealing with Kenneth’s disappearance. Neither the writer or the recipient of this letter were ever identified. It claimed the boy had been kidnapped. “There was a strange man seen up about Barco postoffice and two more places by three different men. He was in a buggy drawn by a black mule and had the boy down between his knees, but the people saw him before they heard the boy was missing. These men say that saw him that the boy was crying and seemed dissatisfied, but the man was talking to him rough.” The writer pointedly added, “Mr. Joshua Harrison went on Tuesday morning and never got back until Sunday. He claimed he had been to Pasquotank.”

|

| Via Newspapers.com |

By February 26, the search had been abandoned. It was universally believed that Kenneth had been abducted, and the smart money had one chief suspect in mind.

That same day, Joshua Harrison paid a call at the Beasley home. It was the first time he and Samuel Beasley had spoken since their altercation over wine.

Harrison was irate over the “News and Observer” article. “It’s a batch of lies,” he told Beasley. “I want you to write to the paper and say it was a lie. If your son was kidnapped some of the neighbors did it.”

Beasley coolly replied that, despite what Harrison was clearly implying, he had not written that letter, and would not bother the newspaper’s editors.

Harrison left, vowing that he could prove where he was when Kenneth disappeared.

The Beasley family continued their sad search for the boy. Samuel and his son Moran spent days fruitlessly combing the woods. No clues emerged pointing to Kenneth’s possible whereabouts until March, when the family received a visit from a Shiloh resident named J.J. Pierce. Pierce had seen Kenneth once, three years earlier. And just recently, on March 5, he thought he saw him again, on a Norfolk street car. The child was with two young men who both appeared to be drunk. Pierce said he addressed the boy, but he did not answer.

Norfolk. Joshua Harrison’s daughter, Anna Gallop, kept a boarding house in Norfolk. Hmmm. Samuel went to Norfolk and asked around, but no one claimed to have seen any boy resembling Kenneth. Other rumors and tips came in now and then, and Samuel doggedly investigated them all, with equally empty results.

In September 1906, Beasley attended the opening session of Currituck Courthouse’s fall term. There, he was accosted by T.C. Woodhouse, brother of the shopkeeper. This man had quite an interesting tale to tell.

Woodhouse stated that on September 2, Joshua Harrison had met him on the road, asking for a “heart to heart talk.” Harrison said, “Sam Beasley has never offered enough reward. When he does, the boy will show up in as good condition as he ever was.” He added, “It was damned expensive to keep the boy in the way he is being kept.”

Beasley was stunned. He frantically told Woodhouse to tell Harrison that he would pay any amount of money for Kenneth’s return, promising that no questions would be asked and he would not prosecute. A day or two later, Woodhouse told Beasley that Harrison denied having made his earlier remarks, and refused to discuss the matter further.

Then, an A.B. Parker came forward. He told Beasley that a few days after Kenneth’s disappearance, he overheard Harrison say that “The boy wasn’t lost; that he could put his hand on him any time he wanted him.” Parker was asked the obvious question: why had he kept this fascinating news to himself?

“It was none of my business,” he replied.

The oddly long-delayed revelations kept coming. A storekeeper named J.L. Turner now said that on the day Kenneth vanished, he had seen Harrison driving a buggy pulled by a black mule, containing a boy with his head covered by a tarpaulin. One Millard Morrisette claimed to have seen this same buggy, although he could not say he recognized either the man or the boy. A W.E. Ansell spoke of seeing the mule-drawn buggy with the tarpaulin-covered boy. He could hear the child saying some complaining words and the man speaking to him reassuringly. He was certain the man’s voice was that of Joshua Harrison.

All these men promised Beasley that they were willing to tell their stories in court, under oath. Beasley promptly got a warrant charging Harrison with kidnapping.

When he was arrested, Harrison vehemently denied the charge. More productively, he hired a team of excellent lawyers. His counsel wisely obtained a change in venue--clearly Harrison’s hometown had no great love for him--and the trial was set to begin on March 14, in Pasquotank County.

The trial lasted six days. The previously-mentioned witnesses gave their stories. Still more witnesses corroborated their accounts. During the cross-examinations, the defense brought out a vital point: the road in front of the schoolhouse, was completely open, lined with houses on one side and the sound on the other. It was a busy road, and at the time Kenneth disappeared, the sound was full of fishing boats. Yet nobody in the vicinity claimed to have seen the buggy, the black mule, Joshua Harrison with his distinctive gray beard. How could Harrison have kidnapped the boy in such a public area without anyone noticing?

The defense also offered testimony from Harrison’s family and neighbors that at the time Kenneth disappeared, the defendant was at his home all day, working in his stable yard. Anna Gallop testified that contrary to rumor, Kenneth had never been brought to her boarding house. The prosecution countered this with two witnesses who stated that they had seen Harrison in Norfolk late on the night of February 13.

Faced with all this contradictory witness testimony, the trial essentially hinged on which side was most successful at cross-examination. The jury decided it was the prosecution. On March 19, they returned a guilty verdict.

Harrison’s lawyers appealed to the State Supreme Court, emphasizing the impossibility of their client having abducted the boy without anyone seeing him. They also pointed out the local prejudice against Harrison. The court denied the appeal, and ordered that Harrison be arrested.

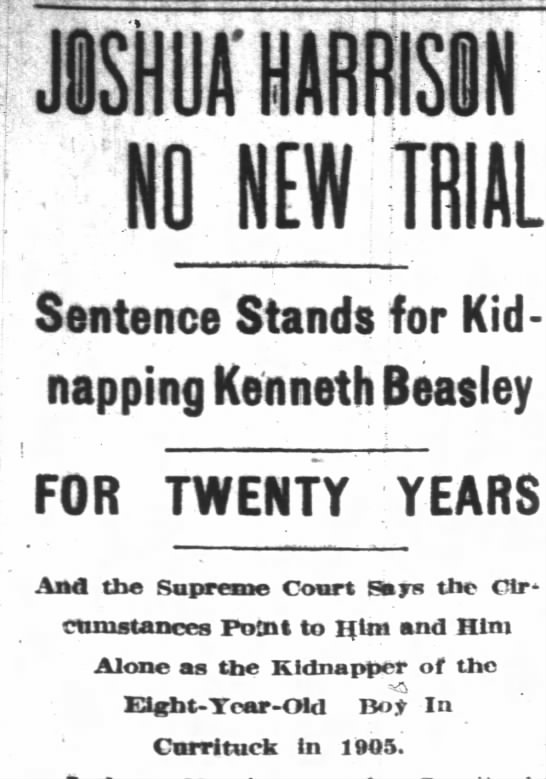

|

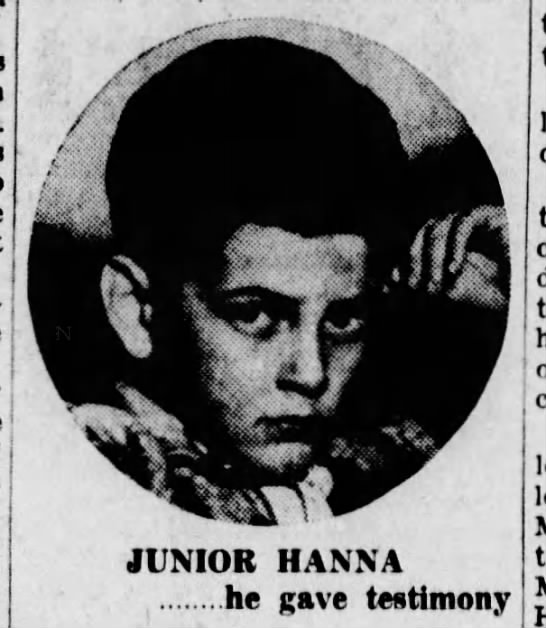

| News and Observer, September 18, 1907, via Newspapers.com |

That same day, as Harrison sat alone in a room of Norfolk’s Gladstone Hotel, a city detective entered the lobby. He instructed the bellboy to summon Harrison.

Harrison slammed the door in the bellboy’s face. A moment later, a gunshot was heard from inside his room. When the bellboy and the detective broke into the room, they found Harrison lying on the floor, quite dead. Next to him was a note he had written, proclaiming his complete innocence.

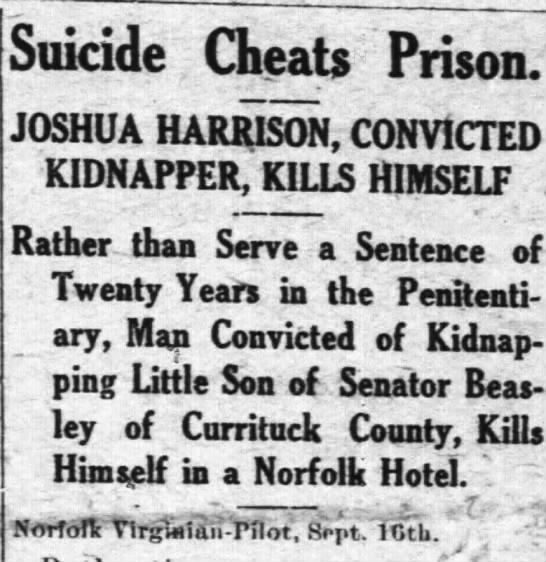

|

| Henderson Gold Leaf, September 26, 1907, via Newspapers.com |

The case was over, if far from resolved. Over the years, Currituck County never really stopped wondering just what had happened to Kenneth Beasley. Among these armchair detectives was a solicitor named Hallet Ward. He was good friends with one of Harrison’s lawyers, W.M. Bond, and the two often discussed the mystery. The two agreed that the case against Harrison had been extremely weak. Also, the people closest to Harrison had argued that while he may have been a hotheaded and even vengeful man, he would never have been so depraved as to take out his wrath on an innocent child.

In 1934, Ward and his family happened to pass through Currituck County. They drove along the sound, stopping for a picnic lunch in front of the building where Kenneth Beasley had once attended school. As they ate, two elderly men walked along the road in front of them. Ward stopped them and introduced himself. He asked if they remembered Harrison’s trial. They most certainly did. As they talked, Ward mentioned the recluse in the cabin, and lamented the fact that law enforcement had never been able to find the man. The two men commented that the hermit had contact only with Joshua Harrison, from whom he bought wine. He also had kept dogs.

Ward suddenly remembered Kenneth’s last words to his mother: “I’ve seen some mighty pretty puppies.”

He and the two men walked along the road where Benny Walker had last seen the boy. As they went deeper into the woods, Ward saw an old rail fence. One of the elderly men pointed to a path on the other side of the fence. That path, he said, led to the hermit’s cabin.

Ward contemplated this new information. So, a path led to the cabin, well out of sight of the main road. He formed a theory: “Kenneth,” he said, “went up that path to that house to see those puppies. Harrison entered the gate in front of the house from the connecting road and picked the boy up at that house and drove on by the back road to the back gate and through it to the Sound Road and on to Norfolk.” Kenneth had no overcoat, and it was a bitterly cold day. That night, he contracted pneumonia and soon died in whatever hideaway Harrison had arranged for him.

Was Ward’s scenario correct? Or--as seems more likely to me--did the anonymous hermit himself use the promise of a puppy to lure Kenneth to his cabin, only to do something unspeakable to the boy? Did he then bury the body somewhere in those woods and flee? Or, on a more hopeful note, could those Carrituck County folk who believed that Kenneth Beasley survived, to be raised in another place, under another name, possibly be correct?

We’ll probably never know.