"...we should pass over all biographies of 'the good and the great,' while we search carefully the slight records of wretches who died in prison, in Bedlam, or upon the gallows."

~Edgar Allan Poe

Friday, August 12, 2016

Weekend Link Dump

This week's Link Dump is sponsored by the Band of Hermit Cats in Caves.

What the hell was the hairy man of New South Wales?

What the hell is Tabby's Star? We still don't know, but it's getting weirder by the day.

Who the hell forged the Piltdown Man? Now we know?

Watch out for those falling witches!

Watch out for those mummies!

Watch out for the Shoe Event Horizon!

Watch out for those bewitched cats!

Watch out for those Voodoo Priestesses! On second thought, you probably already know to do that.

The Broad Mountain Mystery.

What we know--and don't know--about Hieronymus Bosch.

The oldest cave paintings are even older than we thought.

Hell now has wifi, and I'm guessing they use my internet provider.

A "lamented princesse."

Jacques-Louis David, turncoat propagandist.

The bleak story of Scott Joplin.

Ancient Romans took the theft of their clothes very seriously.

Mark Twain vs. the U.S. Postal Service. Judging by the quality of my regular mail delivery, Twain lost.

The Model T and the birth of the middle class.

Babe Ruth and the birth of celebrity product endorsements.

Possibly the world's oldest gold artifact.

A tale of child-stealing fairies.

Stories with headlines like this rarely end well.

The South Shields poltergeist.

A creative Victorian travel journal.

This is old news to anyone familiar with Poe's "The Domain of Arnheim."

Victorian false eyelashes.

I Sing the Victorian Electric.

Henry V and the Battle of the Seine.

A bestiality case in 18th century Wales.

A Victorian woman who was a famed early naturalist.

Some new light on Raoul Wallenberg's fate.

The life-saving qualities of spiced ginger nuts.

How it could be argued that the Inquisition was right, and Galileo was wrong.

That time the Austro-Hungarian empire was invaded by vampires.

That time a mule won a major horse race.

A first-hand account of the storming of the Tuileries.

A--to my eyes, at least--offbeat theory of why the Neanderthals became extinct.

The Flying Pieman of Sydney.

Lizzie Borden, animal lover.

Chronicling the king's letters.

The afterlife of animals.

A haunted furnace.

Victorian tennis costumes.

Rape during the Civil War.

A Neanderthal Marco Polo.

The life of Eleanor of Austria.

The Queen's ass. Luckily, it's not what you might think.

Life insurance fraud for fun and profit.

That "noble knight" Prince Eugene.

Pampered Victorian dogs.

Wayward women in Victorian Cornwall.

Ancient Serbian curse tablets.

The surgeon and the porcupine.

This week's Advice From Thomas Morris: What not to do with a tobacco pipe.

Rowdyism and murder, 1873.

A brief history of dollhouses.

Bronze Age fashionistas.

Twitter is proving to be a bit too much for the Library of Congress. Experts blame my tweets about Victorian children's books.

A near-legendary unsolved murder in Toronto.

The Victorian vegetarians of Torquay.

French toad showers.

The Battle of Romani.

Medieval crime and punishment.

A Napoleonic execution.

And finally, this week in Russian Weird: Cthulhu has been uncovered in a Siberian mine.

That's it for this week. Happy reading, gang, and we'll meet again on Monday, with some ghostly estate planning. In the meantime, here are the Clancy Brothers. Love those guys.

Wednesday, August 10, 2016

Newspaper Clipping of the Day

The sixth installment of the "Boston Post" series "Famous Cats of New England" showcased a fortunate feline one-percenter:

Introducing Button, gentleman of leisure, Beau Brummel of catdom, who intimately knows Senators, opera singers, bank presidents and other people of prominence, and who is without doubt one of the most petted and carefully cared for cats in New England. This cat has his meals served by a faultlessly trained maid; served on a silver tray. So luxury loving is he that he even enjoys having a flower laid on that tray beside the silver dish which bears his monogram. And quite naturally he knows, too, that a finger bowl is not for a well brought up cat to drink from.

"Button" is the property of Mrs. Mary E. Prior, who lives at the Hotel Lenox. He was born in Bar Harbor in the midst of luxury six years ago and brought to Boston when a mere kitten. He has lived ever since in Mrs. Prior's apartment, save for one interruption. That was when moved no doubt by a desire to see the world he plunged one mad morning out of a fourth floor window of the hotel, landing first in a heap in the middle of the sidewalk and later at the Angell Memorial Hospital. It was found he had sustained no broken bones, but feared that a few of his nine lives must have been crushed out by a drop from such a height.

Breakfast is enjoyed promptly at 8 o'clock. The special maid is nearby to wait on his catship. Breakfast menu consists of fried or broiled fish and cream. At 8 o'clock at night Button has a meal of white meat of chicken. He disdains dark cuts.

Including among those whom Button allows the privileges of friendship on whose knees he consents to sit and into which his claws dig delightedly are Senator Walsh, former State Treasurer Charlie Burrill, Addison I. Winship, former civic secretary of the City Club and now a vice-president of the National Shawmut Bank, and many prominent guests at the Hotel Lenox.

Not being a scrapper though in any sense of the word, but merely a gentleman of leisure, he has issued no challenge to the celebrated cats now appearing from day to day in the breakfast table paper of New England.

~December 13, 1920

This was not Button's first taste of publicity. Back in 1916, the "Post" carried a brief article about him in its April 23 issue:

"Buttons” is the name of a young cat that enjoys taking a bath as much as the ordinary human being, and perhaps more. This cat, which is owned by L. C. Prior of the Hotel Lenox, got his name of "Buttons” through its fondness tor collar buttons as playthings.

Mr. Prior threw a collar button Into a partially filled tub of water yesterday, and the cat promptly leaped in. Then the photographer made a flashlight, whereupon "Buttons” gave a mighty spring and ran to the cover of a bed.

"The cat has lived in this apartment since its kittenhood days,” explained Mr. Prior. "Early In its life it learned to enjoy being bathed, with the result that it will now jump into the hath tub with no other inducement than a collar button. Sometimes it will get into the bowl in the lavatory when I am washing my hands. Now and then Mrs. Prior gives 'Buttons’ a shower bath, which he seems to enjoy just as much as the tub bath."

Monday, August 8, 2016

The Hinterkaifeck Mystery

|

| Hinterkaifeck in 1922 |

It is, of course, one of the commonest cliches that "truth is stranger than fiction." Less often mentioned is that fact that truth is far more frightening, as well. No writer of horror fiction, no matter how gifted, has ever been able to come up with anything more terrifying than things that happen on our strange world every day. If these happenings contain an unsolved, and likely unsolvable mystery, it becomes even more chilling. The scariest of all are events that take place, not in times of war or other societal upheaval, but in seemingly quiet, ordinary, safe surroundings.

Which is why Poe or H.P. Lovecraft could never equal the story of what happened to the household of the Bavarian farm known as Hinterkaifeck.

It was a quiet, isolated place located in modern-day Waidhofen, about 40 miles north of Munich. In 1922, much of Germany was still ravaged by WWI. However, the household at Hinterkaifeck was relatively prosperous. It was a one-story building with a small attic. The farm was in two sections: a residential area and barn, separated by a dividing wall. The barn, stable, and livestock areas could be accessed from inside the residential area, as well as through an outer door. The attic covered both sections, meaning that anyone up there could move over the entire building. Although life on the farm appeared stable and peaceful, the residents had a dark, sordid history that may--or may not--have directly led to their deaths.

Five people lived at Hinterkaifeck: 63-year-old Andreas Gruber, his 72-year-old wife Cazilia, their widowed 35-year-old daughter Viktoria and her two children, 7-year-old Cazilia and 2-year-old Josef. The questionable parentage of Viktoria's children was among this story's many grim undercurrents.

It was no secret among the farm's neighbors that from the time Viktoria was sixteen, her father had repeatedly raped her. In 1914, Viktoria attempted to escape her father's domination by marrying one Karl Gabriel. As the couple, at Andreas' insistence, continued to live at Hinterkaifeck, it can be assumed that this action was a complete failure. In August of that year, Gabriel joined the army, and in December news reached the farm that he was missing in action and presumed dead. His body was never recovered. In January 1915, Viktoria gave birth to a daughter. Although her late husband was officially the father, Andreas was named little Cazilia's legal guardian, and odds are good he was responsible for the child in every sense of the word.

In May 1915, a servant accidentally caught Andreas raping Viktoria, and the horrified woman went immediately to the police. Andreas and his daughter were charged with incest. The family patriarch was given a year in prison, with Viktoria serving one month. The scandal never really died out, leaving the family treated as virtual outcasts by their neighbors.

Andreas learned no lesson whatsoever from his jail sentence. After his release, life at Hinterkaifeck went on precisely as before. Viktoria made another attempt to flee life as her father's sexual slave by entering into a clandestine affair with a wealthy farmer from a neighboring village, Lorenz Schlittenbauer. After Schlittenbauer's wife died in the fall of 1918, he proposed marriage to Viktoria. Viktoria, feeling she had finally found the escape route she craved, instantly agreed.

There was, however, one fatal obstacle to their wedding bells: the ever-looming presence of Andreas Gruber. Schlittenbauer suspected--probably quite accurately--that Gruber was still molesting his daughter. When Viktoria announced that she was again pregnant, Schlittenbauer denied the child could be his, asserting that Andreas was responsible. The two men got into a heated argument over the paternity of the expected child, which ended with Andreas threatening Schlittenbauer with a scythe. Gruber vehemently forbade the marriage, and by this point, Schlittenbauer was more than happy to agree. He washed his hands of the Grubers, and poor Viktoria was again left trapped.

After she gave birth to Josef in July 1919, the Grubers insisted that Schlittenbauer acknowledge paternity of the child and pay them child support, but he refused. In September, Schlittenbauer went to the police. He made a formal statement declaring that Andreas was Josef's father. Gruber was arrested and held in custody for two weeks. He was released when Schlittenbauer withdrew his statement. It is not clear why Schlittenbauer made this retraction. He later said it was because Viktoria's family paid him to do so, but by the time he made this claim, the Grubers were not around to either confirm or deny the story. Schlittenbauer soon married another woman, and life at Hinterkaifeck returned to what passed as normal for the farm.

The next notable event came on March 25, 1922, when a little girl named Sophie Fuchs and her mother were walking in the woods near Hinterkaifeck. They were startled to see Viktoria Gabriel sitting on the side of the road, crying and shaking uncontrollably. They tried in vain to comfort the woman. Viktoria was clearly scared out of her mind by something, but she would not say by what. She only said repeatedly that she needed to run away. Not knowing what else she could do, they finally persuaded her to return home. Later, friends of Viktoria's recalled that a few days before this incident, she told them that she had seen a stranger in an army coat watching the farmhouse. When approached, he disappeared into the woods. Was this what was so frightening Viktoria? Or something even worse?

On March 30, things took an even more sinister turn. Andreas found a newspaper in the house, one that the family had never read or brought into the home. He found that the lock on the shed had been broken. Strangest of all, he found in the snow two sets of footprints leading from the adjoining woods to the farmhouse. There were no footprints going in the opposite direction. Several days before, a set of keys had gone missing. Could the household have an intruder? If so, why had nothing been stolen? That evening, the family thought they heard footsteps in the attic above them. They were definitely being haunted, and by something more tangible--and even more alarming--than a ghost.

The next morning, Andreas made a thorough search of the house. He found no one, but discovered that someone had spread straw all over the attic, presumably to muffle the sounds of the footsteps. Later that morning, Andreas and Viktoria went into town to do some shopping. They both told acquaintances about the eerie events at their house. While naturally disturbed by them, the pair did not seem particularly frightened, either. Curiously, they apparently did not consider it serious enough to warrant going to the police.

Around the time Andreas and his daughter arrived home, Hinterkaifeck saw the arrival of their newly-hired maid, Maria Baumgartner. (Their last maid had left the previous August.) Accompanying Maria was her sister, Franziska. Franziska remained for about an hour, helping her sister settle into her new abode, and then she set out for the long walk back to her home.

The following morning, April 1, it was noted that young Cazilia was absent from school. This was unusual for her, but her teacher assumed there was no cause for alarm. Around noon, two coffee salesmen arrived at Hinterkaifeck to deliver an order. The doors were all locked, and no one appeared to be at home. However, they saw nothing suspicious, so they left without feeling any particular concern.

That evening, a Michel Plockl passed Hinterkaifeck on his way home. The place was quiet. Smoke was coming from the chimney, and it had a strange odor of burning fabric. A figure lurking around the courtyard suddenly shined a flashlight into his eyes. Plockl found something so menacing about this sight that he hurried home without investigating any further.

April 2 was a Sunday. The Grubers were not at church, which attracted some notice. Viktoria sang in the choir, and rarely if ever failed to attend. That same day, the family's nearest neighbor, Michael Poell, noticed that Hinterkaifeck was oddly silent. He did not even hear the family dog or any of the farm animals. Monday morning, the postman made his usual visit to the Grubers. He did not see or hear anyone, but as the kitchen door was open, he assumed everyone was merely in another part of the farm.

On Tuesday, April 4, Albert Hofner arrived at Hinterkaifeck. Some days earlier, Andreas had arranged for him to repair an engine. As he approached the house, he heard a dog barking. The animal was shut up in the stables. Otherwise, all was silent. No one answered his knock on the front door. In the distance, he saw a man in the fields who he assumed was the head of the household.

Hofner spent the next few hours working on the engine. When he finished, he returned to the house. He saw that the barn door was now open, and the dog was tied up outside the home. The dog was obviously terribly upset, barking and growling angrily. Hofner noticed that the dog had a terrible gash across the face.

Hofner again fruitlessly knocked on the front door. The door was locked. He found it all extremely weird, but he merely shrugged his shoulders and left. He went to Schlittenbauer's home in nearby Grobern, where he commented on the family's odd absence. He told several other acquaintances of his inability to find any trace of the Grubers, but no one took the news very seriously.

This attitude of indifference was in sharp contrast to the reaction of Lorenz Schlittenbauer. When he arrived home that evening and learned what Hofner had said, he immediately ordered his two sons, Johann and Josef, to go to Hinterkaifeck and see if they could find anyone. They soon returned with the news that the farm was silent, locked up and in complete darkness.

Schlittenbauer went to two neighbors, Michel Poell and Josef Sigl, with a startling announcment. He said he was afraid that Andreas might have hanged himself. The men agreed to make a thorough search of the Gruber farm.

When they arrived at Hinterkaifeck, Schlittenbauer noticed that the barn door was wide open. He led them inside.

What the men saw in the illumination of their flashlights was even worse than a suicide. The barn had been turned into a human slaughterhouse. The bodies of Andreas Gruber, Viktoria, and the two Cazilias were sprawled on the ground, partly covered in straw. Their skulls had all been cleaved open by a heavy weapon such an an ax. Little Cazilia was the worst sight. Her hands were clutching tufts of her own hair. It was believed that she had survived the attack for some hours, lying there conscious and in unimaginable pain. In her agony, the child had fitfully pulled at the hair from her mangled head.

Schlittenbauer went to the back door, where he saw the formerly missing set of keys in the lock. He opened the door, and the stunned, apprehensive men went inside. Their worst fears for the rest of the household were soon realized. Young Josef was in his cot, where someone had hacked him to death. The equally mangled body of the new maid, Maria Baumgartner was in her room just off the kitchen. Her suitcase was still unpacked, suggesting that she had been killed not long after her arrival.

The house did not appear to be ransacked. Money and jewelry was left untouched. Oddly, the only items that may have been stolen were the contents of Viktoria's wallet, which was found lying empty on her bed.

Meat had recently been carved from a livestock carcass in the cellar, indicating that during the period between the murders and the discovery of the bodies, someone had felt secure enough to linger about the scene, eating meals and caring for the farm animals. Food scraps and human waste were in the attic, suggesting that the intruder had been lurking there for some time. There were loose tiles in the roof that would have enabled them to spy on the farm's courtyard and thus keep track of who was entering or exiting the house. It was speculated that the adult Grubers and young Cazilia were lured to the barn, where they were killed one by one. Then, the murderer(s) killed the maid and butchered little Josef in his cot.

Schlittenbauer sent the others to fetch the police. He stayed in this house of blood alone, where, with a curious stoicism, he calmly went to the basement to fetch food for the farm's pigs.

Officers soon reached the scene, with a further group of police from Munich arriving a few hours later. Word of the nightmarish fate of the Grubers had quickly spread through the community, causing a crowd of locals to gather at Hinterkaifeck. These ghoulish looky-loos tramped at will around and through the crime scene, very likely contaminating or destroying whatever evidence might have remained at the sight.

However, even if the spectators had been kept at bay, it is doubtful it would have helped. This proved to be one of those perplexing cases where the police investigation found itself stalled as soon as it began. Lacking a murder weapon, an obvious motive, or eyewitnesses, these peculiarly brutal killings seemed fated to remain a permanent mystery.

It must be said that the police did their best with what little they were given. For years to come, they conducted hundreds of interviews and obsessively analyzed whatever evidence they could uncover. The authorities grew so desperate they even removed the victims' heads and sent them to a clairvoyant in Munich. If they could not solve this crime, perhaps the spirit world could! This psychic (whose name is lost to history) stated that there had been two killers, and that the murder weapon was hidden somewhere on the property. As the spirits were not helpful enough to provide names and addresses of the guilty parties, this information was ultimately a waste of time. (The heads were sent to Nuremberg, where--in a final act of violence--they were destroyed by allied bombing in 1944.)

Researchers into the case have looked at several possible perpetrators, all of them unsatisfactory in one way or another. Heading the list was Lorenz Schlittenbauer. His unsavory and antagonistic links to the Grubers made him an obvious focus of suspicion. It was also felt that he took the discovery of this mass butchery--one where the victims included his ex-lover and a child he might have fathered--with an unnatural calm. And although he had visited Hinterkaifeck on only one or two occasions, after the murders he seemed to immediately know where everything was inside the house. Many of his neighbors felt his guilt was obvious. However, others saw Schlittenbauer as a mild-mannered, gentle man who was simply incapable of the depraved brutality of these murders. Solid evidence against him was completely lacking. And how could he linger around the crime scene for so long without being missed at his own home? For what it's worth, policemen who interviewed Schlittenbauer simply could not see him as a mass murderer.

A robbery that went strangely, horribly wrong? Then why did the thieves leave money and other valuable property behind? And why would they linger at the farmhouse for several days afterward?

An intriguing story was related by Hinterkaifeck's former maid, Kreszenz Rieger. She told police that during her time at the farm, a neighbor named Josef Thaler had repeatedly tried to seduce her. She stated that he showed a great familiarity with the layout of the house. Thaler also told her that Andreas Gruber hid a lot of money on the farm, and he, Thaler, knew exactly where it was. Thaler and his brother Andreas were known burglars. Some months before the murders, Andreas Gruber had caught them attempting to steal from the farm, and chased them off with a rifle. A year or two after the Grubers were killed, a relative of the Thaler brothers warned Rieger that if she continued to accuse them of the murders, they would kill her. Suggestive as all this may be, it was still not enough to tie them to the crime. And if they were the killers, why did they not rob the place as well?

The oddest theory pointed the finger at Viktoria's missing-in-action husband, Karl Gabriel. It was speculated that perhaps he was not killed in battle, after all. Could he have been the mysterious man Viktoria said she saw lurking about the farm, come to avenge his unhappy married life in the worst way possible? Alas for this Agatha Christie-like proposal, it was firmly established that although Gabriel's body was never recovered, several of his comrades had witnessed his death. Although the Gruber household was one where it seemed that virtually anything was possible, one can feel fairly confident in saying that at the time of the murders, Karl Gabriel had long been well and truly dead.

The "usual suspects"--a lunatic who escaped from a hospital some seventy miles from Hinterkaifeck, local petty criminals, various bad apples--were all considered by the police, but ultimately rejected for lack of evidence.

The (headless) bodies of the Grubers and Maria Baumgartner were buried in a ceremony attended by over 3,000 people, and life went on. Andreas Gruber's brother and sister entered into a nasty court fight with the surviving relatives of Viktoria's husband over the ownership of Hinterkaifeck. To make a long lawsuit short, if young Cazilia had died after her mother, the next heir would be the child's paternal grandfather, Karl Gabriel Sr. However, it was impossible to legally establish the order in which the victims had died. The dispute was eventually settled out of court, with the Gabriels gaining control over the farm in exchange for a cash settlement to the Grubers.

The following year, the Gabriels had Hinterkaifeck demolished. While this was being done, the murder weapon--a homemade mattock belonging to Andreas Gruber himself--was discovered hidden in a false floor by the fireplace. As significant as this find originally seemed, it did absolutely nothing to help find the killer.

Police continued interviewing witness and following possible leads as late as 1985. It was all fruitless. The deaths at Hinterkaifeck seem destined to remain not merely Germany's eeriest mass murder, but its most baffling.

Friday, August 5, 2016

Weekend Link Dump

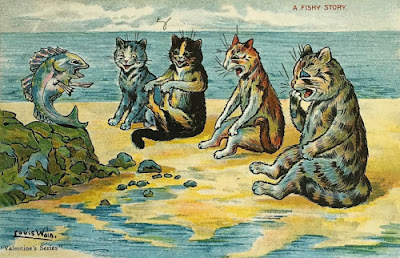

This week's Link Dump is sponsored by the Louis Wain Cats of Summer!

What the hell was the Caithness Mermaid? (Final word here.)

What the hell were the voices in Joan of Arc's head?

Watch out for those Kansas river monsters!

Watch out for those murderous ghosts!

Watch out for the Witch of Scrapfaggot Green!

The mysterious end of the last Franciscan missionary in Texas.

This week's Advice From Thomas Morris: How not to get pregnant.

This week's Advice From Thomas Morris II: Watch out for those flying jaws!

Solving the mysterious death of a 19th century scientist.

The scientist who's taking family reunions to a whole 'nother level.

A Paleolithic sculpture has recently been discovered.

The spiritualists meet Lizzie Borden. Hilarity ensues.

Why you shouldn't impersonate the king of Portugal.

The 17th century poet Anne Bradstreet.

Indonesians have interesting funerals.

The mystery of the 80 shackled skeletons.

How to be a good Georgian wife or husband.

Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness.

Those weird and wonderful witches.

Hindu temples with musical pillars.

Harriet Westbrook, who had the misfortune of marrying Percy Shelley.

Victorian life preservers.

The strange death of the "Mayor of the Fillmore."

The Great Warsaw Basilisk Hunt.

The immortal Spanish Prisoner.

The ghost armies of Souter Fell.

Anna of Denmark, art patron.

WWI "cigarette delivery dogs."

The maladies of midwives.

The Case of the Defrauded Dachshund.

What you'd wear to a Victorian fancy dress ball.

A few relatively little-known facts about France.

An 18th century clergyman looks forward to his wedding night in true 18th century fashion.

Thomas Grey runs afoul of Henry V.

The licking stones of Carlisle.

Those naughty bicycle messenger boys.

Hitler's Olympic village is still standing.

The kind of things you find when you go digging with Andy Mould.

A notorious 1841 murder.

The secret lives of cadavers.

The link between the Civil War and Egypt's cotton industry.

Victorian women's fondness for archery.

The bottom of the ocean is one strange place.

Mark Twain takes a famous raft trip. Or does he?

Blind people see for the first time...during near-death experiences.

You find some interesting things in old parish records.

Cats vs. ghosts.

This week in Russian Weird presents the 75-year-old reindeer carcass of Doom.

Not to mention the drunken Russian pilot and the bombing of Mecca.

And we're done for this week! See you on Monday, when we'll visit one of the creepiest crimes in German history. In the meantime, hello, Dolly:

Wednesday, August 3, 2016

Newspaper Clipping of the Day

Mystery Floods and Mystery Glass-Breaking, in the same story? Yes, please. This Canadian report comes from the "Toronto Globe" for September 9, 1880:

Wellesley, Sept. 6--A very extraordinary story having gained currency in this section of the country that Mr. George Manser, a very respectable and well-to-do farmer residing near the village of Crosshill, in the township of Wellesley, had with his family been driven out of his dwelling by the mysterious breaking of his windows and showering down of water in dry weather, your correspondent took occasion to-day to visit the place and interview Mr. Manser and his family in regard to the report in circulation. On approaching the house he noticed the windows, six in number, closed up with boards, which still further excited his curiosity and gave reason to believe that there must be some ground for the report.I was unable to find any further details, but from past experience, I'm guessing the nut remained uncracked.

The house I found to be a large one-and-a-half story hewed log building, rather old but in a very good state of repair, situated a short distance from the highway on the most elevated part of the farm. On stating the object of my visit Mr. Manser very kindly showed me through the building and gave me the following facts:

About a month or six weeks ago the glass in the windows began to break, several panes bursting out at a time. These were replaced with new ones only to meet the same fate. A careful examination was then made to ascertain the cause. It was at first supposed that the house being old and getting a little out of shape might affect the windows, but the sash was found to be quite easy and even loose in the frames. Then the family are surprised and put to flight with a shower of water, saturating their beds, their clothing, in fact everything in the house, whilst the sun in shining beautifully in the horizon, and outside all is calm and serene. Nothing daunted, Mr. Manser repairs to the village store and obtains a fresh supply of glass, and even tries the experiment of using some new sash, and utterly failing to discover the mysterious cause of either the breaking of the glass or the sudden showers of water, all taking place in broad day light. His neighbours are called in, and whilst they are endeavouring to solve the mystery, a half dozen or more panes of glass would suddenly burst, making a report similar to that of a pistol shot. Mr. Manser states that he inserted more than one hundred new lights of glass and then gave it up, and boarded up the windows, first taking out the sash and setting them aside, but on account of the continued bursts of water, they were compelled to remove all their beds, some to the wood-shed and others to the barn, leaving only those things in the house that are not so liable to be damaged by the showering process to which he has been so repeatedly subjected. He has commenced the erection of a new dwelling, hoping thereby to escape those remarkable tricks of nature, or whatever it may be, which seem to continue their operations to the old house. If these strange occurrences had taken place at night, one might suspect that Mr. Manser was the victim of some mischievous people, but occurring in the daytime in the presence of the family and other witnesses, and in fine weather, it seems very difficult of solution. Various theories have been put forward, but none of them seem sufficient to account for the double phenomena of the sudden showers of water under a good roof in fine weather, and the oft-repeated bursting out of the windows. Perhaps you or some of your scientific readers can crack the nut.

Monday, August 1, 2016

The German Princess

Some people become royal through an accident of birth. Others become royal through marriage. And some, like the heroine of today's post, gain a royal title as a result of thievery, prostitution, bigamy, and general all-purpose grifting. Meet Mary Moders, who for one brief but epic season became the toast of London as "The German Princess."

Moders was born in Canterbury, England, probably on January 11, 1642. Her father was said to be a reasonably successful musician. We know little of her early days, although her early biographer Charles Johnson stated that she was an enthusiastic reader of romances and adventure tales, a habit which inspired her to put on airs of "a Princess or a Lady of high Quality." Reality, unfortunately, intruded into these dreams. Instead of marrying, as she believed was her right, a "baron or squire, or knight of the shire," she was forced to settle for a shoemaker named Thomas Stedman.

Moders, however, remained certain she was born for bigger and better things. Before too many years had passed, she abandoned her cobbler and their two children. She made her way to Dover, where, with the fine disregard for legal niceties which characterized her whole career, she entered into another marriage, to "a Surgeon of that Town." Word having gotten around about her superfluous husband back home, she was indicted on a charge of bigamy, "but by some masterly Stroke, which she never wanted on a pressing Occasion, she was quickly acquitted."

She then went to Cologne, Germany, a city that had always appealed to her. Having somehow obtained a tidy sum of money, she took up residence in a "House of Entertainment, and lived in greater Splendour than she had ever done before." That summer, she frequented the fashionable German spas, where a rich, elderly gentleman fell in love with her. He showered her with money, expensive jewels, and finally proposed marriage. Moders accepted, but decided it was more prudent to take her money and run. She gathered together her ill-gotten gains, pausing only to scoop up her landlady's hidden hoard of cash as well, and fled to Amsterdam.

Moders returned to England in March 1663. She traveled to London, where she found lodgings in the Exchange Tavern. She told her landlords, a man and wife named King, that she was Lady Henrietta Maria de Wolway, only child of John de Wolway, a German earl and sovereign prince of the Empire. Alas, she had married a nobleman without her father's permission, causing this cruel parent to banish her from his dominions. The "melancholly Relation" of this "unfortunate German princess" so touched the hearts of her listeners that the Kings gave her all the money they had available, with the promise of more to come.

Goodbye plain Mary Moders; hello glamorous German Princess.

Mrs. King had a brother, a young lawyer's clerk named John Carleton. What better match for him, the lady reasoned, than this charming foreign aristocrat? She wasted no time introducing the pair. Although the princess warned him that her stern father "would make War upon any Prince who extended his Pity to her," Carleton was soon begging her to marry him. After displaying a natural amount of reluctance to give her royal hand to "one of common Blood," she accepted him, and three weeks after they first met, they were married. The pair settled down in Durham Yard, with Carleton frequently thanking his bride for "the prodigious Honour" she had bestowed on him by consenting to become his wife. Carleton poured all his money into providing her with clothes, jewels, carriages, and servants suitable for her illustrious rank.

After about two weeks of wedded bliss, Carleton's gratitude quickly dried up when he learned that Mr. King had received an anonymous letter informing him that his princess was "a Cheat and an Impostor." The Carleton family, showing all the natural rage of people who discover that they had made first-rate fools of themselves, marched on the princess' residence, where they impounded all her clothes and jewelry, "knocked her down," and hauled her in front of magistrates. She retorted by accusing Carleton of tricking her into marriage by pretending to be a wealthy aristocrat, and initiating a bogus prosecution against her when she turned out not to be as rich as he thought.

While sitting in jail awaiting her second bigamy trial, she entertained a steady stream of visitors who were anxious to see London's newest curiosity. They found her witty, spirited, and quite magnificently unrepentant. She was regarded as something of a public heroine. In the meantime, her quondam husband, John Carleton, attempted to counter his new role as public laughingstock by publishing not one, but two pamphlets defending himself and bitterly railing against "this two-legged Monster," the "Canterbury German," a "Production of an infamous brood, dropt from an Ale-tap, and the filthy base extraction of a Dunghill...a Storehouse of untruths, an Armory of falsehoods, a Castle of Impudency, a Treasury of Vice, an Enemy to all good." "Ladyes and Gentlemen," he pleaded, "imagine what you should have thought had you been in my place and Condition; had you heard her speak thus, seen her deportment, and had accompanyed her so much as I did; and observed her probably storyes and circumstances...and to have found her so ingenious a Woman (as indeed she is, to give the Divil his Due,) and were she honest she were excellent."

His efforts to redeem his reputation did little good. Public sympathy was very clearly with the princess. London has always loved its rogues, and in the former Mary Moders, they had a superb example of the breed. Poor Mr. Carleton just came off as a humorless whiner.

Moders pled Not Guilty at her Old Bailey bigamy trial. In the courtroom, she merrily greeted her bridegroom, exclaiming "What a quarrel and noise here's for a cheat! You cheated me and I you. You told me you were a Lord and I told you I was a Princess; and I think I fitted you!" She continued to laugh at him during the course of the proceedings. "My Lord," she told the judge, "by all that I can observe of the Persons that appear against me, they may be divided into two sorts; the one of them come against me for want of Wit, the other for want of Money."

Moders continued to insist she had been born in Cologne. She admitted having been married to Carleton, but as for her first marriage, she simply said, in effect, "prove it."

The prosecution had a surprisingly hard time doing that. Stedman himself declined to make the trip to London to testify against Moders unless he was given money for the journey. There was only one living witness to her marriage, a man named Knot. His testimony was considered inadequate evidence to prove bigamy, which was then a capital offense. Accordingly, the jury returned an acquittal, a verdict which was greeted with cheers from the spectators.

After she was freed, this notorious and beguiling figure was naturally urged to pursue a career on stage. She appeared in a number of productions, generally playing "either Jilt, Coquette, or Chamber Maid, either of which was agreeable to her artful intriguing Genius." A play, "The German Princess," was written as a starring vehicle for her. Although Samuel Pepys greatly admired Moders' "wit and spirit," he dismissed the show with the words, "never was any thing so well done in earnest, worse performed in jest upon the stage." Despite this bad review, she attracted "a considerable number of Adorers," most of whom, naturally, wound up being fleeced of their money. She also supplemented her income with a long string of brazen and elaborate con jobs. Charles Johnson sighed that "It would be impossible to relate half the Tricks that she play'd, and mention half the Lodgings in which she at Times resided. Seldom did she miss carrying off a considerable Booty wheresoever she came; at best she never fail'd of something, for all was Fish that came to her Net."

These good times could not last forever. Before too long, she was back in Newgate, charged with stealing a silver tankard. She was found guilty and sentenced to death. However, her uncanny good fortune in courts of law held out enough for the sentence to be commuted to being transported to Jamaica.

She remained abroad for two years, after which she pushed her luck by returning to England and passing herself off as a rich heiress. In this role, she married a "very Wealthy Apothecary at Westminster, whom she robb'd of above £300 and then left him."

This was her last great triumph. In late 1672, she was brought down by an accident of fate. A Southwark brewer named Freeman was robbed of £200. He enlisted a Mr. Lowman, Keeper of the Marshalsea Prison, to help him find the thief, who he suspected was a man named Lancaster who was often found in New Spring Gardens. While Lowman and his assistants were searching that area, "they spied a Gentlewoman walking in the two-pair of Stairs Room." Lowman quickly recognized her as that renowned fraud, the German Princess, who was, the law thought, safely in the West Indies. He immediately arrested her for violating her sentence of transportation.

Moders' trial in January 1673 was short, albeit not sweet. In response to being asked why she returned to England so soon, she could only make "trifling Evasions to gain Time," which managed to stretch the proceedings out for several days. Lacking any other form of defense, she finally "pleaded her Belly." After a "Jury of Matrons" determined that she was not pregnant, our Princess knew her last card had been played. She faced the inevitable death sentence "with a great deal of Intrepidity."

While awaiting her hanging, she entertained an "abundance of Visitors," and expressed fervent--and, who knows? possibly sincere--regret for her long, highly criminal past. Moders went to the scaffold on January 22 with all the élan one would expect from such an energetic and engaging adventuress. On the last day of her life, we are told "she seemed more Gay and Brisk than ever before." In a charmingly weird gesture, she went to Tyburn with a picture of John Carleton pinned to her sleeve. It is not recorded whether she did this out of sentiment or a desire that he symbolically share her fate.

Londoners wrote many eulogies, pamphlets and ballads celebrating their lost Princess, the "Crafty Whore of Canterbury," but considering the humor she consistently brought to her deviltries, she would probably have most appreciated the epitaph suggested for her by some anonymous "merry Wag":

The German Princess here, against her will,

Lies underneath, and yet, oh strange! lies still.

Friday, July 29, 2016

Weekend Link Dump

This week's Link Dump is sponsored by the Feline Symphony Orchestra!

What the hell was the Canton Church Apparition?

Watch out for the Nevada Triangle!

Watch out for those phantom postmen!

Watch out for those cursed lakes!

Watch out for that undertaker ice!

If you happen to be a mermaid, watch out for Caithness!

A 50-year-old murder still haunts one New Jersey city.

A history of bloodletting.

Poe the Time Traveler!

A duel between 18th century royals.

A clandestine marriage made by an 18th century royal.

England's first umbrella.

More proof that we really know little about human history.

How the 19th century beat the heat.

The words that are eating themselves.

A Latvian fortress complex.

A murder mystery at Lamb's Gap.

An 1843 ghost riot.

Police raid a Victorian cross-dressing ball.

The Zines of Renaissance England.

The legendary ghost of Benjie Gear.

18th century lighting.

18th century women's cricket teams.

The downside of being a Roman emperor.

Encountering the Fairy Hunters.

This week's Advice From Thomas Morris: What not to do with an umbrella.

A forgotten martyr of WWI.

The power of community memory.

Traveling tips from the early 19th century.

A restored Victorian house in Oregon.

Leaves that are relics of a king's death.

Cows in the Oxford English Dictionary.

The family scandal of Constantine the Great.

18th century lotteries.

Lady Alice and Sir Tom of the NYPD.

A crime writer who might also be a murderer.

The wedding of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon.

Political snowball atrocities.

Murderous Ohio.

The Ottoman siege of Belgrade.

Using mermaids to cure cancer.

A tribute to wasps.

A notorious early 19th century murder.

A Civil War killer rabbit.

The last woman to be hanged in Newfoundland.

The death of Napoleon's son.

The real "English patient."

The weird disappearance of a New Mexico girl.

A modern-day literary hoax.

The mermaids of Congo.

And, finally, this week in Russian Weird: Siberia's not just sinking, it's bouncing.

So there it is for this week. See you on Monday, when we'll be looking at a very unusual princess. In the meantime, let's hear the Flying Burrito Brothers:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)