|

| "Muskogee Phoenix," August 10, 1935, via Newspapers.com |

One of my favorite minor categories of Weird History is the Libelous Tombstone. Surprisingly often, loved ones create memorials that focus less on eulogizing the deceased, and more on settling scores and generally venting spleen.

And bloggers of my particular sort bless them for it.

Murder accusations are a favorite topic for this particular type of grave marker. A story similar to the example above was reported in the "Savannah Morning News," August 28, 1904:

A murder charge on a tombstone, made by the family of the victim, which the courts of Mississippi have not confirmed, involves the grand lodge of the Woodmen of the World of Omaha, Neb., in an embarrassing position. It has several hundred thousand members, mainly in the South and West, and is facing a situation that will become a precedent for benevolent organizations.

A summary demand on the grand lodge of the Woodmen of the World to remove a monument erected by the order from the grave of a dead member on account of a dispute over the inscription is the outgrowth of the famous Lawson-Semmes murder case.

Dr. F. G. Semmes of Hickory, a wealthy man, was indicted for the murder of T. D. Lawson, and on the filing of a habeas corpus was admitted to $12,000 bail. Eminent lawyers of Mississippi are defending him.

Lawson, as a member of the order under its constitution received a monument. The family of Lawson selected a Scriptural epitaph, which was sent to the grand lodge and approved. Morris Brothers of Memphis contracted to erect the monument. Meantime a local agent at Hickory, at. the request of the dead man’s family, had Morris Brothers change the inscription, without the sanction of the grand lodge.

The words "T. D. Lawson, kiiled by F. G. Semmes." were inscribed instead of the original approved words. As Dr. Semmes does not admit the murder and the words convict him of the deed, the matter was appealed to the grand lodge by the friends of Dr. Semmes, and this body ordered the monument-makers to remove the words and substitute the original inscription. This was done.

The Lawson family thereupon immediately demanded of the grand lodge that the monument be removed from the grave. A second and more insistent demand has now been made for its removal.

The grand lodge, under its constitution, must erect a monument for every dead member, no matter where the body is located, and will have to set up the monument somewhere. It is the first case of its kind, and on account of the numerical strength of the order in the South and all the parties involved being members it has created a sensation.For anyone interested, at his trial, Semmes admitted shooting Lawson, but claimed it was self-defense. He was acquitted. I have no idea what finally happened to Lawson's monument.

A queer case has been recently tried at Marshall, Mo. A man named Potter had a son drowned while bathing in the Blackwater, with two men named Finley and Beggs. The boy's father believed that foul play had been done, and caused a stonecutter named Tiffing to erect a tombstone over his son's grave with the inscription: "Rock of ages cleft for me, let me hide myself in thee. Drowned in the Blackwater by Philander Finley and Mort Beggs." The parties thus charged brought suit against Potter, and have recovered $800 damages.

A farmer at Allschwil, near Basle, recently lost his young wife—and also her dowry, a fairly large sum, which on her death went to her relations under the marriage settlement.

The husband was annoyed at losing the “dot” and in revenge ordered a large marble tombstone, with an inscription dwelling on the defects of his wife's character. It ended by saying that she had taken her dowry “to heaven or hell, probably the latter place.'’

Every evening a small crowd collected in the cemetery before the unusual tombstone. Eventually the family of the dead woman appealed to the communal authorities, who ordered the tombstone to be removed within a week. The family’s libel action against the husband will go on all the same.A rather curious case was heard in London in 1954. The following report comes from the "Evening Standard" of April 7:

Bessie Solomon, 27, who claims that she was libelled by an inscription on her mother's gravestone, told the High Court today about a religious ceremony at which the stone was consecrated by a rabbi.

The inscription read: “In loving memory of Rose Simmons who went to her eternal rest on October 27 1950 aged 43 deeply mourned and sadly missed by her sorrowing husband Mark son Eddie daughters Betty and Alicia.” Miss Solomon, the court have been told, is always known as Betty.

Miss Solomon, slim and dark-haired, was asked how she felt when she read the inscription. She replied “I was surprised, my brother was surprised But it was not the sort of place to have any quarrels or arguments."

Mr. Bernard Gillis, counsel for Mr. Mark Simmons, one of seven people Miss Solomon is suing, asked her: “You would not wish to do anything which would have caused your mother any feelings of distress?" Miss Solomon replied: “ Not if I could have avoided it while she was alive." "Now that she is dead does that mean you have no regard for her reputation or memory?" — "I have the same feelings about her." "You cherish her memory?" —"Yes."

Miss Solomon, who gave her address as Thurlow Place, Kensington, alleges that the inscription on the gravestone—in Golders Green Jewish Cemetery—imputes among other things that she is illegitimate.

The defendants are Mr. Mark Simmons of Westminster Court, Aberdeen Place, St John's Wood, a bookmaker with whom Miss Solomon’s mother was living at the time of her death, Mr Albert Elfes, stonemason, Plashet Road, Upton Park, Mr. J.H. Valentine, keeper of the cemetery, and four trustees of the West London Synagogue of British Jews who own the cemetery. All deny that the inscription it bears is defamatory or that it bears any of the meanings which Miss Solomon alleges.

Miss Solomon said that her parents separated when she was three. First she lived with her father, but in 1942 on returning to London after evacuation, she went to her mother, who was living with Mr Simmons. “I called him Uncle Mark" she said.

When her mother died Miss Solomon did not attend the funeral—it was not the custom for women to do so. She learned that a gravestone was being brought from Italy. She attended the consecration ceremony, her father did not.

Mr Gillis — "Which name do you say your mother would have preferred on the gravestone: Rose Simmons, by which she was known for many years, or Rose Solomon?" "Miss Solomon— As Mr Simmons was already married before the stone was set up it is hard to say."

Miss Solomon added that she was upset about the part of the inscription which referred to “husband Mark.”

Mr. Cyril Salmon QC for the trustees — "If your mother was known as Rose Simmons why are you bringing this action?" Miss Solomon—"I am trying to clear my name." "The alternative to bringing the action was to let the matter rest?"— "Yes." "Why did not you adopt that alternative?" — "Mr. Simmons is not my father."

The jury found for the defendants.

A case from Budapest was reported in the "Columbia Missourian," August 4, 1926:

The inscription upon a tombstone here has given rise to one of the most unusual lawsuits in the annals of Hungarian courts.

A few weeks ago, Julius Fall, a clerk, argued with his wife whom he accused of unfaithfulness. Mrs. Fall indignantly denied the accusation."I swear by the life of our little boy," she cried, "that I have never deceived you in our marriage."

Shortly after this scene, the 6-year-old son died suddenly. This tragedy moved Fall to petition for a divorce. The death of his son, he declared, was the reply of fate to the oath sworn by his wife. The boy's death, he insisted, proved that God was avenging his wife's alleged adultery.

Happening to pass by the cemetery one day, Mrs. Fall discovered that the tombstone on her son's grave displayed a verse, the first letter of each line spelling her middle name. Translated, the poem read: "The slumber of death wrested me from you,And your guilt stifled my blossoming life..."

Mrs. Fall promptly sued her husband for libel. The court sentenced Fall to two months' imprisonment and ordered the removal of the inscription from the tombstone.More family troubles appeared in the (Stoke-on-Trent) "Evening Sentinel" for February 22, 1980:

A court at Baltimore, Maryland, awarded £875 in damages to a woman who sued her brother for ordering this inscription on her father's tombstone: "Stanley J. Gladsky, 1895-1977, abused, robbed and starved by his beloved daughter."

The daughter, Gloria Kovatch, claimed she was libelled and held up to public scorn by the inscription, which resulted from a family dispute.Yet another legal fracas was reported in the "Muskogee Daily Phoenix" for July 26, 1923:

CHATTANOOGA July 25 — "Can a tombstone be libelous?” This is the question which the Hamilton county grand jury will be called upon to answer here.

Authorities from Walker county, Georgia, served notice that they would appear before the local inquisitorial body and ask the indictment of R.D. Baker for criminal libel as the result of erection of a tombstone near here to George Baker, his son.

The tombstone bears the inscription that the boy had been unjustly hanged at La Fayette, Georgia, for the murder of Deputy Sheriff Norton near there last summer.In order to avoid prosecution, Baker removed the offending words from the stone.

Raleigh—An old mountaineer freed in 1917 from a murder charge may soon win his lengthy battle for eradication of a libelous tombstone inscription.

Hamp Kendall, a 71-year-old native of Lenoir, served 10 years for a murder he did not commit. He was later pardoned and the State paid him about $5000 for his servitude. However, as Kendall recently told a nation-wide radio audience, the murder victim’s tombstone in a Lenoir cemetery still carries an inscription stating that the deceased was “murdered and robbed by Hamp Kendall and John Vickers Sept 25 1906.”

Vickers died shortly after his release from prison. But Kendall is still very much alive and he wants the slur erased from the tombstone.

Kendall appealed to the Governor and other officials to have the imputation removed. All his efforts were in vain, however, as State law prohibits molestation of tombstones.

Yesterday a solution to the problem came to light. A North Carolina legislator from Lenoir introduced in the Senate a bill that would make it “illegal to erect or maintain a gravestone bearing an inscription charging anyone with the commission of a crime.” If the bill is passed and enacted into law Kendall probably will have no trouble getting a new marker.

The Monument Builders of America have already offered to erect without charge a new monument over the body of Lawrence Nelson, the victim. This offer was made the day that Kendall appeared on “We the People,” a CBS coast-to-coast program. He related over the air the story of his trial imprisonment and life after servitude.Happily for Kendall, his efforts to have the inscription removed were successful.

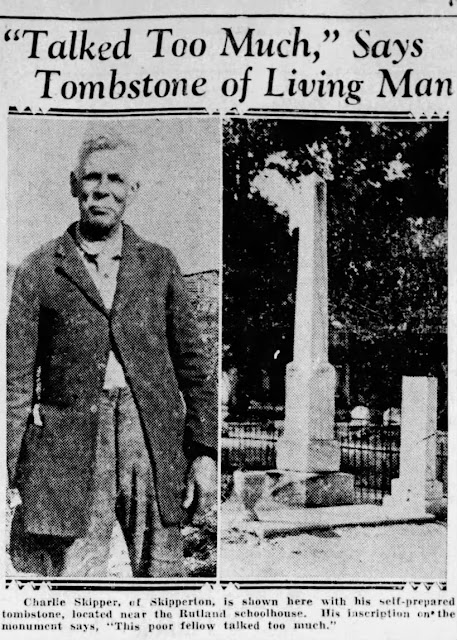

In Skipperton, a sleepy, sunny little farm settlement about 10 miles from Macon, they wonder all kinds of things about why Charlie Skipper put his own monument up in the cemetery 20 years ago with the strange epitaph “This poor fellow talked too much.”

Some say he has made a will, the reading of which after his death will solve the matter, and it has been hinted that his second marriage had something to do with it, but nobody knows and all agree that no satisfaction is to be got out of Charlie himself about it.

Anyway, in the little country cemetery behind Rutland school there it is—a big seven or eight-foot marble shaft with a broad triple base between two marble slabs with carved backs and marble vases for flowers for the tombstones of his two deceased wives.

The lot, about 50 feet square, is fenced with a picket fence the gate bearing in iron letters, Skipper. When one enters the gate one notices the queer sentiment carved on the back of Charlie Skipper's premature monument in simple slanting marble letters, “This poor fellow talked too much.”

The gravestone of his first wife, Ella L. Skipper, tells that she was born in 1862 and died in 1904, while the second wife was considerably younger and died not quite two years ago.

Coming upon Charlie Skipper at work on his truck farm one finds him to be a jolly old fellow full of sly jokes and chuckles of enjoyment. He seems so jolly, in fact, with his white hair, sturdy weathered face and white mustache, that one thinks his very drawling chuckling love of cracking a joke throws some light on the strange monument and epitaph.

“Well,” he explained quite simply, “I just thought I better put this monument up while I had the money before I wasn't able nor my children neither."

And that's all there seemed to be to it—except his reason for such a singular choice of an epitaph.

“Well they all say around here I talk too much or a mighty lot anyway,” he offered with a grin, and added, “I just thought I'd help ’em out.”

“It's been there 20 years and maybe I ain't dead yet—but mighty near it!” he insisted, shaking his head and smiling.

Mr Skipper doesn’t look by any means “mighty near it.” He's so hale and hearty and young for his 70-some years that one can hardly imagine his ever resting under the handsome marble shaft that he prepared so long ago. And the thought would seem forbidding and gloomy to anybody, but Mr Skipper who declares heartily and happily that: “No it don't makes me feel bad to have it there; it makes me feel good to know it's all ready for me when I need it!” because he seems to figure that “I ain’t got so much longer I guess.”

He maintains that he keeps as young as he is now by exercise in the form of hard work on his farm that begins at 4 o'clock in the morning and lasts until 8 at night. And though he claims to be a “mean fellow” his chief vices are chewing tobacco and smoking a cigar on Sunday. He never drinks since prohibition which is “a great thing to keep whisky away from ’em."

He and his brother George, for whose father he believes the town was named, are the last of the two Skipper boys left there. He has the following children living in Macon: Mrs. Mattie Parker, Mrs. Beulah Burke, and B.F. Skipper.

So perhaps there isn't any weird mystery in a man's preparing his own grave some 20 years before he dies. It seems to be simply that Charlie Skipper thought he'd better do it while he had the money. But one wonders if there isn't something to 'old Charlie's joke about “helping 'em out” in their contention that he “always talked too much.” He seems to be the kind of fellow who would depart this life leaving a last chuckle behind him.I like Charlie. The old boy clearly had the Strange Company spirit at its finest.

Boy, some people carry grudges beyond the grave - their own and others'...

ReplyDeleteIn another approach to tombstones, I remembered reading somewhere that after WW I the British government allowed soldier's families to provide short inscriptions for their relative's tombstones. Apparently, lists of these are online, and a few are very critical of the government policies. I can't find the details - they must be on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission site somewhere; perhaps I need an account - but I found this article

ReplyDeletehttps://inews.co.uk/news/ww1-first-world-war-somme-commonwealth-war-graves-commission-remembrance-armistice-210693

Which included “Shot at dawn, one of the first to enlist, a worthy son of his father.”

And I found some minutes in which "Just for a scrap of paper" was approved.

I have to admire those old bureaucrats for including tributes so critical of the war effort.

I've never heard of those! Yes, that's very interesting that such statements were allowed. Perhaps more than a few of those bureaucrats weren't so pro-war...

Delete