Ella Maude “Nell” Cropsey is romantically remembered as “Beautiful Nell,” even though her surviving photos suggest someone of no more than average attractions. (A contemporary once bluntly described her as “plain.”) Whether the sobriquet was deserved or not, it illustrates how her enigmatic end has obtained a lasting legendary status in the area where she spent the last few years of her life. After all, as Poe famously wrote, “the death, then, of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.”

Nell Cropsey was born in Brooklyn, but in 1898, her family moved to Elizabeth City, North Carolina, in order to take up farming. Before long, the seventeen year old girl was courted by a young man named Jim Wilcox.

Unfortunately, we don’t know very much about Wilcox as a person. Although legend has it that Jim was considered a strange young man, that may well be apocryphal. One gets the impression that he was an ordinary, decent enough fellow who, in normal circumstances, would pass through life essentially unnoticed.

Jim and Nell’s romance did not remain a happy one. By the time they had courted for three years, trouble began to develop. Nell, it was said, began openly flirting with other men, and she frequently treated Wilcox with indifference, or even outright rudeness. Jim, according to his later story, resolved to end this increasingly acrimonious relationship.

Such was the uneasy state of affairs on the evening of November 20, 1901, when Wilcox arrived at the Cropsey home.

Nell and Jim sat in the parlor with her sister Olive (known as “Ollie,”) a visiting cousin, Carrie Cropsey, and Ollie’s beau, Roy Crawford. They spent the evening in the way all playful young people have done from time immemorial, by...uh, discussing their favorite methods of committing suicide.

Jim declared that he would choose to drown himself. “Oh, I wouldn’t,” Nell chirped. “I’d rather freeze to death.”

By about 11 p.m., Jim decided he had had enough of this cheery banter, and rose to leave. According to Ollie, as Jim was exiting, he stopped and whispered to Nell that he wanted to speak to her. Nell looked back questioningly at her sister, who nodded her assent.

Now we come to one of the many disputed points in this frustratingly murky tale. Some say that as Jim and Nell stood together on the porch, they had a loud, vehement quarrel. Others say they spoke so quietly, it was impossible to overhear what they were saying. At around 11 p.m., a neighbor named Caleb Parker drove his buggy past the Cropsey home. He later said he saw two figures standing on the sidewalk, but it was too dark to say for certain who they were.

Meanwhile, inside the house, Carrie retired for the night. Roy Crawford left immediately afterward. He claimed that both Jim and Nell were gone. At 11:45, Ollie went to the porch to call Nell to come in, but got no reply. Presuming Nell had slipped back inside and gone to bed, she went up to her sister’s room. It was empty. Puzzled, a bit concerned, but not yet really alarmed, Ollie went to bed.

Around midnight, a loud commotion broke out in the Cropsey back yard. Their dogs began barking furiously, and their pigs let out anguished squeals. Ollie heard a neighbor yelling, “Cropsey! Cropsey! Someone’s after your pigs! Get your gun!”

Ollie joined her father William in the hallway. When she told him that Nell and Jim were out there somewhere, the irritated father assumed they were the cause of the disturbance. However, when William Cropsey went out to the yard, there was not a human to be seen.

When William returned to the house, he learned that Nell was still absent. It was becoming obvious that something was wrong. Mr. Cropsey stormed over to the Wilcox home and banged on the door. When Jim’s still half-asleep father answered his knocks, William demanded to see Jim. He wanted to know where his daughter was.

Mr. Wilcox was surprised. He said that Jim had been in bed since midnight. A few moments later, young Wilcox appeared, in his night clothes and looking as sleepy as his father. When William asked what had happened to Nell, Jim seemed genuinely surprised. He insisted that he had left Nell on the Cropsey front porch around 11:15. He had not seen her since.

William went straight to the home of the Police Chief. The two men searched Cropsey’s house and grounds. They searched the yards of all the neighbors. No Nell.

The pair marched back to the Wilcox home and ordered that Jim tell them exactly what the hell had happened that evening. Jim told them that at 8 p.m., he went to the Cropseys to return Nell’s photo and an umbrella she had given him. He had not planned to stay, but Ollie had urged him to spend the evening. At 11, he asked Nell to go outside to talk. He gave her the photo and umbrella and told her that all was over between them. She began to cry. He watched helplessly for a few minutes, and, wanting to escape this uncomfortable scene, he said he had to meet a man. Nell stopped weeping long enough to snap, “Well, go on then!”

Jim left. Naturally upset by what had just happened, he walked aimlessly for a short time--maybe half an hour--encountering a friend, Leonard Owens, along the way. The two chatted for a few minutes. (Owens confirmed that this meeting took place.) Wilcox went to a bar and had a beer. And then he went home.

The Police Chief did indeed find the umbrella at the Cropsey home, but Nell’s photo was missing. He decided the best thing to do would be take Jim into custody until the mystery of the girl’s disappearance was cleared up. This proved to be no easy task. Bloodhounds followed Nell’s trail from the porch to the Cropsey summerhouse, and then to their boathouse. No further. The river was dragged, and virtually every home in and around Elizabeth City was searched. No sign of Nell was found.

It never pays to be the last known person to see someone who has mysteriously vanished. It rapidly became the near-universal opinion that Jim Wilcox, in some still-unknown way, was responsible for Nell’s disappearance. He was formally charged with abduction, but until Nell--or her body--reappeared, the case remained at a standstill.

Jim was repeatedly questioned, but he stuck to his initial story. Meanwhile, the usual number of “sightings” poured in. People came forward claiming to have seen Nell all over North Carolina.

On December 24, William Cropsy received an anonymous letter postmarked Utica, NY. The author claimed to know what had happened to Nell. According to this writer, Jim Wilcox left Nell crying on the porch. She stood there for some time, until she heard the family dogs barking. When she went to the back yard to investigate, she found a man she knew stealing a pig. When she threatened to tell her father, the man knocked her out with a stick, carried her to the river, dumped her in a boat, and rowed away with her. The writer had no idea if she was alive or dead at that point. This man was named in the letter, but his identity was never publicly revealed.

This informant went on to say that her body would be found at a certain point in the river. He/She even included a helpful diagram of the spot. It was 150 yards from the Cropsey boathouse. Very oddly, Cropsey seems to have ignored the letter, not even bothering to tell the police.

His indifference became even stranger when five days later, fishermen found Nell’s body in the exact place indicated by the anonymous writer. Presuming she had died on the night she was last seen, it was noted that her corpse was unusually well-preserved. It was also considered strange that the site where she was found had been repeatedly searched.

When word swept through the town that Nell had finally been found, the police had a very hard time saving Jim Wilcox from a date with a lynch mob. It took surrounding the jail with the State Guard for the would-be assassins to finally disperse.

Once the public decides someone is a murderer, it is easy for them to find “proof” of the charge. Evidence began mounting pointing to Wilcox’s guilt, but unfortunately, a lot of it was of questionable veracity, and all of it circumstantial. It began to be said that, in fact, Nell had been the one to break off their romance. It was claimed that, a few days before Nell vanished, Jim had tried to get her to go sailing with him (cue ominous music) but Nell was afraid to be on a boat with him, and declined. He then took Carrie Cropsey and another of Nell’s sisters out on his boat. Just before the trio returned to the house, it was claimed that Jim, as a “joke,” suggested wrapping one of the girls in a blanket and carrying her into the house, as if she were dead.

The coroner came to the somewhat mystifying conclusion that Nell had died as the result of “being stricken a blow on the left temple and by being drowned in the Pasquotank river.” However, no water was found in her lungs. Medical experts never did agree if she died from being hit on her head or from drowning. The blow, it was determined, had been caused by a padded instrument, like a blackjack.

The authorities decided that all of this was enough to justify putting Wilcox on trial for murder. It was a very hard job to get twelve men willing to say they had not already made up their minds about the defendant’s guilt. Meanwhile, the same unknown person who had written to William Cropsey sent another letter to Jim Wilcox’s father. This informant continued to insist that Jim was innocent, giving the same account of Nell’s death given in the previous letter. The alleged real murderer was, according to the newspapers, “familiar to all Elizabeth City people.”

|

| "The North Carolinian," February 5, 1903, via Newspapers.com |

The prosecution argued that Wilcox was the only one to have the means and opportunity to kill the girl. As for motive, they claimed that Wilcox wanted to dump Nell, but feared the resulting scandal. They described Nell as a “happy, healthy girl” who had no reason to kill herself. They produced medical witnesses who testified that Nell was already dead when she entered the river. In response, all the defense could do was insist that Wilcox had no idea how Nell had died, and they suggested that, distraught at being jilted, she had drowned herself. Wilcox himself did not take the stand.

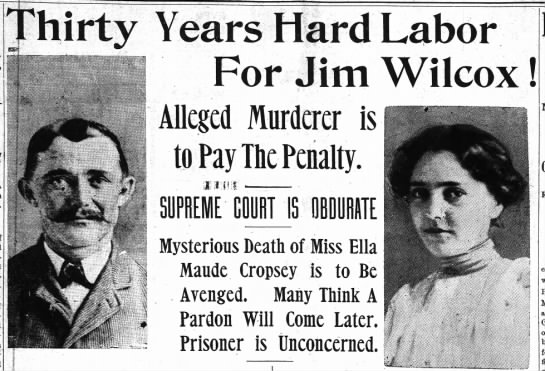

While the jury deliberated, there were numerous reports that if Wilcox was found not guilty, he would be kidnapped from jail and lynched. It was even suggested that the jurors themselves would be in grave danger if they did not return the approved verdict. To no one’s real surprise, the jury voted for a conviction, and Wilcox was sentenced to death. However, his lawyers, citing the extreme prejudice against their client in Elizabeth City, were able to win him a new trial in another county. Wilcox was again found guilty, but this time merely for second-degree murder. His life was spared, but he faced a long prison term. As he was heading to the penitentiary, Wilcox told a policeman, “There is a little fire smoldering in Elizabeth City which might break out in three months, or it may be three years, but it will break out sooner or later, when the truth will be known which would then relieve me of the burden of somebody else’s sin.”

|

| "The Tar Heel," June 12, 1903 |

Wilcox was in the state prison until December 20, 1920, when the Governor, Thomas Bickett, granted him a pardon. As three earlier attempts to pardon Wilcox had failed, Bickett’s change of heart remains a mystery. Roland Beasley, a long-time North Carolina newspaper man, stated that Wilcox had told the Governor something which convinced Bickett of his innocence. Beasley said that before Wilcox was pardoned, Bickett told him that there was an explanation of Nell’s death which would exonerate Wilcox. The Governor added that he was going to talk to the prisoner in person, and “If he says what I think he probably will say, I expect to pardon him.” Unfortunately, it was unrecorded why Bickett came to believe Wilcox was not guilty.

Wilcox was no longer a prisoner, but it is a stretch to say he became a free man. He spent his life living as a hermit in the woods. He once explained that he knew nobody wanted him around. He became destitute, sick, despondent, and usually drunk. To the few people who would talk to him, he continued to insist he was entirely innocent of Nell’s murder. He added that he was certain that William Cropsey knew who had killed her. After fourteen years of this bleak existence, he finally had enough. In December 1934, he took a shotgun and blew off most of his head.

To this day, people in Elizabeth City ponder the riddle of Nell Cropsey’s death. Among the residents obsessed with the mystery was one William E. Dunstan. In his book “Nell Cropsey and Jim Wilcox: The Chill of Destiny,” he gathered together local recollection and gossip to put together his scenario of what actually happened on that long-ago November night.

According to this version of events, Nell had secretly been having an affair with a married neighbor, John Fearing. Her “romance” with Wilcox was merely a cover for this illicit relationship. After Jim returned Nell’s photo and umbrella, he left, leaving her standing on the porch. After Wilcox’s departure, Fearing, who had been concealing himself nearby, approached Nell. As the two passionately kissed, William Cropsey--who was known to have a violent temper--came outside. Enraged by his daughter’s unmaidenly behavior, he impulsively hit her. Unfortunately, the blow was so violent he accidentally killed her. Cropsey and Fearing were equally horrified by this sudden death, and equally anxious for a cover-up. Both their reputations would be ruined if the truth came out. With the possible aid of Ollie, Roy Crawford, and Nell’s brother Will, the girl’s body was concealed in the family icehouse until they could decide what to do with her. A plot was hatched to make Jim Wilcox the fall guy. Although there is no way to prove this is what really happened, it would explain some of the oddities surrounding Nell’s death, such as the striking lack of decomposition and the fact that she had been found at a spot which had been previously searched.

Dunstan suggests that it was this dark deed which led to the subsequent tragedies which plagued the Cropseys. Both Roy Crawford and Will Cropsey eventually committed suicide, and Ollie ended her days as a recluse, troubled, it was said, by mental instability. Nell, it seemed, haunted everyone who had been close to her.

If Dunstan’s reconstruction is at all correct, Nell Cropsey’s death was no average accident or murder, but an epic Southern Gothic tragedy.

While Dunstan's scenario would explain the suicides in the family, it seems far-fetched. Why not just leave Nell's body where it was and say that they found her like that after Wilcox had gone? And who wrote the mysterious and highly knowledgeable letters?

ReplyDeleteThe letters really bug me. From the old newspaper accounts, I got the distinct feeling authorities knew--or at least suspected--who wrote them, but for some reason, this was kept hidden. It's also pretty strange that the "real" murderer named in the letters was never publicly revealed. This is one of those odd cases where a lot of people were keeping a lot of secrets.

DeleteNot so odd. Maybe William Cropsey was an influential person of The contemparary town or had secrets about The town council etc. It was easier to blame a boy, than to reveal many other person's... To take The risk of being uncorrupted...

DeleteI do feel that Jim Willcox was most definitely the fall guy

ReplyDeleteThey were talking about suicide and Nell said that her method would be to "freeze to death". Perhaps after the bust-up with Wilcox she went to the icehouse to do just that. Wilcox guessed her intentions and came back, causing the commotion at around midnight, but he either found her already dead or was scared off before reaching her.

ReplyDeleteHer body was preserved by the cold and then whacked on the head and dumped in the river to make it look like murder. Realistically, this must have been done by her family, probably assisted by Crawford. Wilcox just kept their secret.

Their likely motive is that suicide was considered a mortal sin. They were protecting her reputation and her soul by ensuring that she would get a proper Christian burial. That also explains why Bickett pardoned Wilcox without explaining his reasons.

In this theory, the letters were fabricated as part of the cover-up. William Cropsey didn't do anything with them because he knew or suspected the truth. The authorities didn't release any names because they suspected the same, and they knew that rumours could get people lynched.

It would actually also help explain why, when a lynch mob did attempt to get at Wilcox, Nell's parents were the ones to talk the mob down, until soldiers could be sent in to guard the jail. If they had all agreed to cover up a suicide, they probably couldn't, in good conscience, allow Wilcox to be killed for something he did not do.

DeleteWow - three people connected with the disappearance committed suicide.

ReplyDelete