|

| “The Witches’ Cove,” Follower of Jan Mandijn |

This week’s Link Dump is sponsored by representatives of Halloween Cats United!

|

| “The Witches’ Cove,” Follower of Jan Mandijn |

This week’s Link Dump is sponsored by representatives of Halloween Cats United!

I’ve posted a number of Halloween cautionary tales on this blog, but I doubt I’ve shared a weirder one than this. From the “Cork Mercantile Chronicle,” November 22, 1802, via Newspapers.com:

The sports of Halloween have been described by the fascinating Burns, but, whether in a way to deter from indulging in them, admits of a doubt. That they have, in more than one instance, terminated lately, we have heard that they did so, in one instance, and that so late as last week we know--We give the following particulars from authority, and our informant trusts that they will prove a warning to inconsiderate youth to betake themselves to amusements more rational, and less likely to be attended with unpleasant consequences to themselves:

The ceremony of sowing hempseed on Halloween, is known to most of our readers. A young girl of the name of Mabel Carr, servant to Mr. Mathewson, type-founder, would needs have her Halloween on Monday week; and, notwithstanding the earnest remonstrances of her master, who represented the impropriety and absurdity of prying into the secrets of futurity, she would not be dissuaded from sowing her hempseed on that night. About ten o’clock she accordingly went into the foundry alone, with a light in her hand, which she placed on one of the tables while she performed her incantations. She walked through the shop several times pronouncing aloud the words used on such occasions and so anxious was she to see something, as she termed it, that having seen nothing, she gathered up the seed to sow it a second time. In the course of this second sowing, according to her own account, a tall meagre figure presented itself to her imagination! She shrieked aloud, and ran immediately into the house, all the doors being open. After relating all that she had seen, she went to bed, placing the Bible under her head! She rose on Tuesday, and went through the labours of the day in apparent good health; but in the evening appeared somewhat timid. She, however, had her supper, as usual, and went to bed, without any symptoms of fear. Next morning she was called, but did not answer; again was called, but still no answer. A daughter of Mr. Mathewson’s then rose, went to her, and found that she was very sick, and that she had been so during part of the night. Tea was ordered for her, but before it could be prepared, she was seized with a stupor; the pulse became sunk, and breathing difficult, and the hands swollen and blackish. A Medical Gentleman was instantly called. He said, it was an attack of an apoplexy which she could not survive more than ten minutes; and in rather less than that time she expired, the blood bursting from her nose, mouth, etc. The surgeon, on being informed of the transactions of Monday night, was clearly of opinion, that the impression made on her imagination by the fancied apparition was the cause of this fatal catastrophe.

We have given the particulars of this unfortunate affair so minutely, because reports, injurious to a very worthy man, have gone abroad on the subject. It has been stated that one of Mr. Mathewson’s men concealed himself in the foundery, to alarm the girl during her foolish probation. It is false. Mr. M.’s people leave off work at eight o’clock; this happened at ten; and there was not a soul within the shop but herself. It has been further stated, that she fell into a faint on the appearance of the fancied spectre, and was left to die in that situation. It will be seen, from the above authentic statement, that this is an absolute falsehood, and a most malicious one.

So, however, you celebrate Halloween this year, avoid the hempseed. Unless, of course, you want to see something.

And now that I think of it, if you read this blog, you probably do.

|

| "Cape Vincent Eagle," December 22, 1927 |

One day in the spring of 1865, a stranger arrived in a small Northern New York hamlet called Fishers Landing. He was so silent and secretive, it ironically earned him what was undoubtedly unwanted attention. Years later, a Watertown newspaper recalled that the visitor was “very reticent and refused to talk of cities he had visited or say where his home was located.” This curious traveler was no ordinary vagrant--he was well-dressed, intelligent, and was obviously what used to be called “a gentleman.” He was described as about thirty, with swarthy skin, black hair and a noticeable southern accent.

The man took a hotel room, where he holed up for some days. Then, he moved to Clayton’s Maple Island, in the middle of the St. Lawrence River. He built a crude lumber hut, which, as it turned out, would be his home for the rest of his days. He almost completely disappeared from human view, with no company except a supply of books and his violin. He only left the island to make rare visits to local farms to buy food and other basic necessities. He paid for his purchases with British gold.

One night in the fall of 1865, the area was hit by a violent storm. When it was observed that a fire had broken out on Maple Island, those on shore assumed it had been struck by lightning. Then, three or four men could be seen running around the island, presumably Good Samaritans helping Maple Island’s sole resident escape the flames.

The next morning, when some of the locals went to the island to offer assistance to the hermit, they found that something far grimmer had taken place. The hut had been burned down, and his boat and stash of gold pieces were missing. The hermit’s body was found near the shore on the opposite side of the island. He had been, in a reporter’s graphic words, “literally chopped to pieces with an ax or other sharp weapon.”

Although it was assumed that the motive for the murder was robbery, no one had any idea who committed this gruesome deed. It was said that a week before the murder, three strangers with southern accents had arrived in the area. On the day of the murder, they rented a boat. After they returned the boat late that night, they hired someone to row them to Alexander Bay. They were never seen again. If these were indeed the hermit’s killers, it does not appear that anyone even tried to have them traced. After the coroner gave the mangled remains a cursory examination and the corpse was buried on a strip of sandy beach near the burned out-hut, the investigation into this killing was essentially over. (Regarding this burial, in 1891, a local resident claimed that in 1877 “a certain Wall Street broker, now dead,” had robbed the grave of the hermit’s skull, which he had made into a tobacco box.)

In the years following the hermit’s death, people have had a great deal of fun speculating about who this man was and why he was killed. According to some reports, his murderers had slashed his chest with three crosses in the shape of a triangle. This was known to be the symbol of the Knights of the Golden Circle, a pro-Southern, pro-secession secret society. That led to the theory that the murder of the hermit was some sort of assassination carried out by the Knights. Many people found it plausible that this reclusive southern gentleman was somehow involved with that ever-popular inspiration for wild legends, the Lincoln Assassination. In 1896, the “Watertown Re-Union” pointed out that Jake Thompson, a Toronto-based agent for the Confederacy, had paid John Surratt $100,000 in English gold to help assassinate Lincoln, Grant, Sherman, and other Union leaders. Surratt was accompanied by John A. Payne, brother of Lewis Payne, who would later be hanged for his attempted assassination of William Henry Seward. John Payne was said to be the treasurer of the Knights of the Golden Circle.

Some authorities came to believe that the hermit may well have been John Payne. According to this scenario, it was Payne who was actually given the $100,000 which was meant to be divided up among the would-be assassins. Instead, Payne fled with the gold and hid himself on Maple Island, hoping to remain invisible until the coast was clear. Unfortunately for him, his former co-conspirators succeeded in tracking him down, whereupon they took their bloody revenge.

For what it’s worth, this story was corroborated years later by one Robert McAdam. As he was on his deathbed, he confided to a friend that he had been another member of the secret society to which Payne belonged. McAdam and Payne had been part of the plot to kill Lincoln. McAdam was supposed to get a share in the gold Payne had received. After Payne betrayed them, he had been one of the three men who had killed him. After all, by running off with the gold, Payne had broken his oath of loyalty to the Knights, which, according to the rules of the society, meant death.

In 1914, the daughter of a now-dead woman named Jenny Hickey shared her mother’s story. Hickey had been a dairy maid at one of the farms which sold food to the hermit. She was often assigned to deliver these goods to the hermit’s island hut. As the man was handsome and personable, she enjoyed making these visits.

Understandably, Jenny became very curious about why such a charming and cultured man chose such a lonely, sparse existence. When she questioned him, he was reluctant to share anything about himself, but she was able to learn that he had fought for the Confederacy under Stonewall Jackson and Lee. He showed her a book of Confederate war songs, revealing that he was the author of one of them, the “Death of Jackson.” The songwriter was listed as “John A. Payne.” The hermit begged Hickey to never reveal his identity, as it could well cost him his life. A few days later, Hickey’s sailor fiance returned home after a long voyage, and they were soon married. She never returned to the farm, and never saw the hermit again.

However, local historian A.E. Keech dismissed all the Payne stories as “pure fiction.” Keech also refuted the allegations that the hermit’s body had been found mutilated with crosses. According to him, after the fire on the island, the hermit merely vanished forever. He believed the mysterious man was really another southerner, Godfrey J. Hyams. During the Civil War, Hyams was first assistant to Toronto’s chief Confederate commissioner. In 1864, he learned of the Confederate plot to burn down New York City, and tipped off the Federal authorities. As a reward for this bit of double-dealing, he was paid $100,000 in cash, after which he wisely fled town. On his way to Halifax, he realized he was being followed, so he changed his route and sought an obscure hiding place, which he found on Maple Island. As with the Payne theory, the Keech scenario has him murdered by the men he had betrayed, with his body either spirited away or lying on the bottom of the river.

Was the hermit a former Confederate who paid the ultimate price for disloyalty to his friends? Or, more prosaically, was he just some ordinary uninteresting citizen with, for whatever reason, a strong taste for solitude? (To be frank, I lean toward the latter.) In either case, the tale of the Hermit of Maple Island provides New York’s Thousand Islands region with its most colorful legend.

|

| "The Witches' Cove," Follower of Jan Mandijn |

It's Friday morning!

Are you ready for Saturday night?

Watch out for those deadly clouds!

A brief history of California social novels.

The black cat train.

Mayans had remarkably sophisticated water-filtration systems.

What we know--and, more often, don't know--about Viking children.

Science, I've found, is always unsettled.

A tour of British graveyards.

The strange death of John Edwards.

Jane Rebecca Yorke, the last person to be convicted in Britain for witchcraft.

A horse-saving blacksmith cat.

The murder of Carrie Brown, which was at one time attributed to Jack the Ripper.

Raise your hand if you didn't need science to tell you that animals are capable of grief.

The name "Selina Cordelia St. Charles" belongs in a romance novel, and you could say that such was the case.

1942: the year when it looked like America would lose the war.

Greg Fleniken ranks high in the ranks of really, really unlucky deaths.

Another reason why I find Teddy Roosevelt really obnoxious.

In search of Eliza Armstrong.

Some legendary female ghosts.

The mystery of the levitating priest.

In 16th century Milan, it didn't pay to be an insatiate Countess.

I feel better about never achieving my childhood goal to become an archaeologist when I realize how much time they spend around ancient poo.

Can't decide what horror film to watch this Halloween? Just consult your astrological sign.

Funeral men as messengers of death.

A ghost and the Franklin Expedition.

The ambush of the liner SS Persia.

Remembering artist Rosa Bonheur.

Well, this is one way to avoid being executed.

A real wicked stepmother.

The murder of Andy the Goose.

Why you wouldn't have wanted to work for Marconi Systems.

A particularly bizarre murder.

Why French royals used to smell like crap. Literally.

Nazca has a cat!

The medieval life of Matilda Marshal.

The colonial legacy of the Mayflower.

A palm print caught a murderer...or did it?

In and out of the Eagle: the world of 19th century London entertainment.

When Woodrow Wilson caught the Spanish Flu.

3,000 year old ball games.

Tales from an 18th century highwayman.

Photos and eyewitness accounts of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

The weird world of animal adaptations.

The ongoing controversy over the lost Roanoke colony.

The significance of ancient cow DNA.

How to plan your next Ghost Cat road trip.

The ever-popular 50 Berkeley Square.

One for the Weird Wills file.

The lore surrounding ringing rocks.

A dream leads to a murder.

That's all for this week! Tune in on Monday, when we'll look at the lore surrounding a mysterious hermit. In the meantime, anyone else remember this one?

|

| Via Newspapers.com |

This odd little story--I suppose you could call it “poltergeist lite”--appeared in the “Pickens Sentinel,” May 14, 1891:

Bennettsville, S.C., May 1--There was a mysterious occurrence in Bennettsville a few nights ago, which has puzzled the most philosophical minds. Many theories have been advanced, yet the mystery remains unsolved. Doors and windows are barred at night; nocturnal pedestrians ambulate the streets with lighted lanterns; the cracking of a twig or the rustle of the wind causes a sudden halt and rapid pulsations of the heart.

For two months Mr. P.C. Emanuel has been living in Mr. St. P. Covington’s house in East Bennettsville. This is comparatively a newly settled place, splendid building, surrounded with sweet and luxuriant flowers, situated in one of the most desirable neighborhoods in town.

On the night in question, Mr. Emanuel and wife had just retired, but had not gone to sleep. The moon was shining brightly, everything being quiet and serene. About 11 o’clock, the report of what seemed a gun was heard at the bed chamber window. The shot was plainly heard falling in the room. Mr. Emanuel is not a timid man by any methods. He has plenty of nerve and scarcely can be frightened by ordinary means. He at once concluded that some one had accidentally shot into his room, but directly a second report, at the same place, was repeated.

Mrs. Emanuel was terribly frightened. Her husband lowered the lamp, rushed to the window, threw open the blinds, and discharged his pistol in the direction of the ground. For a minute or two all was quiet, when suddenly, in his room, near his trunk, in rapid succession, two reports of what seemed to be pistol shots, were heard. After a short interval there were two reports under the house, directly under the bedroom, and just at that moment the house shook and crockery were rattled, and a noise was heard as if glass were being ground in a mill, and simultaneously every rooster in the neighborhood commenced crowing.

Mr. Emanuel says he was sure that judgment day had arrived, and that he had no other thought but that in a short time he would be facing the Immaculate Judge. Mr. Emanuel vacated the house at once, and the place is now unoccupied, where “goblin damns” can hold high carnival. Mr. Emanuel is an honest, truthful, and intelligent citizen, and the above facts were recited to The State correspondent by him in a special interview.

|

| "Brighton Gazette," April 7, 1831, via British Newspaper Archive |

It’s often said that the duty of journalists is to “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” However, one newspaper man gave his own fun twist to this motto. While he did indeed “afflict the comfortable” to a marked degree, the only “comfort” his efforts provided was to...himself.

On April 10, 1831, a London-based former schoolmaster, druggist, and itinerant preacher named Barnard Gregory expanded his resume by launching a weekly publication called “The Satirist, or, The Censor of the Times.” And a whole lot of important people would soon be very sorry he had.

“The Satirist” billed itself as “For King, law, and people.” In some respects, it was a standard newspaper--it carried reports from Parliament, and the occasional straightforward news story. It’s true purpose, however, was to mock and defame people, institutions, and public issues Gregory had a beef with.

This proved to be an impressive list. Gregory despised lawyers (“the black sheep of the law,”) gaming houses, the church (“a mass of corruption,”) the death penalty, and--unsurprisingly--the stamp duty on newspapers. On a more personal level, “The Satirist” hurled abuse on both political reactionaries such as the Duke of Wellington, and radicals Henry “Orator” Hunt and the Chartists. Queen Victoria was treated comparatively respectfully (although the newspaper disapproved of her disinterest in English theater,) but the Prince Consort was a favorite target, largely because he was a foreigner. (Among the most unpleasant things about “The Satirist” were its extreme xenophobia and crude anti-Semitism.)

Politics, however, played a minor role in the pages of “The Satirist.” It’s true mission was to print scandalous gossip about the lascivious, and even criminal, doings of society’s highest classes. The publication loved nothing better than to expose the hypocrisy of the aristocracy and gentry, who set themselves up as a superior class, while indulging freely in behavior that would make less-favored mortals publicly disgraced or jailed. Gregory didn’t hesitate to name names and specify their acts of alleged wickedness, often neatly evading the libel laws by making his claims through clearly fictitious “letters to the editor.” Gregory would publish responses to these “correspondents” in terms such as “We cannot really reply to ‘Looker-On’ as to what the Countess of Beauchamp and William Burton are doing at Worthing. Perhaps our correspondent can inform us?”

“The Satirist” finally went too far when it suggested that the recent birth of a child to a Mr. and Mrs. Neeld came as an unpleasant surprise to the husband, who had only recently married his wife, and that this new little Neeld was directly linked to Mrs. Neeld’s “close intimacy with an officer in the Guards.” Unsurprisingly, Mr. Neeld immediately went screaming for the lawyers, bringing a suit over what the Attorney-General called “one of the most wicked and malignant libels” he had ever seen.

This opened the floodgates. Suing “The Satirist” became a popular London pastime. It was a very good time to be a lawyer specializing in defamation laws. Many members of the legal profession became fat, rich, and happy, thanks to Mr. Gregory. In 1832, he was convicted of libeling a lawyer named Deas. The following year, he was nailed for accusing a Brighton man of cheating at cards. In 1839, defaming and attempting to blackmail the wife of Tory MP Sir James Hogg earned him three months in jail. Then Gregory made the mistake of attacking Renton Nicholson, the editor of a rival publication named “The Town.”

It is never a good idea to insult a man with ready access to a printing press. Nicholson gave better than he got, publishing a long expose of Gregory which confirmed what most had suspected: “The Satirist” was merely a vehicle for blackmail. Gregory would publish defamatory stories about his victims, then hit them up for money to get him to stop. For Gregory, it was a win-win: either his target gave in and paid handsomely, or they held firm and refused, thus allowing him to continue publishing all that lovely circulation-boosting dirt. Gregory’s efforts to sue Nicholson over these articles were derailed when he was imprisoned for the Hogg affair.

Gregory was also hauled into court by the Marquess of Blandford, son and heir of the Duke of Marlborough. Blandford was, if possible, an even sleazier character than Gregory. “The Satirist” noted that the Marquess, in order to seduce a seventeen year old named Susan Lawson, had tricked her into thinking they were married. It was only when Blandford decided to marry an heiress, Lady Jane Stewart, that he bluntly informed Lawson that their “marriage” had been a hoax: the clergyman who had conducted the ceremony was merely an army officer paid off to do a bit of playacting.

Mr. Justice Denman, who was given the unappetizing role of presiding over the suit, made it clear he was equally disgusted with both defendant and plaintiff. If there was a judicial way to make both sides lose, he would have found it. When giving his judgment, he commented that if Blandford alone had been injured by “The Satirist,” he would have found against him, because, well, the creep deserved it. However, these published revelations also wounded Blandford’s innocent wife and children, not to mention the teenage girl who had been so cruelly deceived. By way of warning “those who are disposed to traffick in character in this way that they cannot be allowed to do so with impunity,” the judge found against Gregory.

Even this debacle was topped by Gregory’s protracted legal battle with Charles, Duke of Brunswick, known, not without reason, as the "Mad Duke." At least, he had been Duke of Brunswick until 1830, when his subjects, fed up with his eccentric and heavy-handed rule, launched a successful insurrection against him. Although the ex-duke made spasmodic efforts to reclaim his position, no one in Europe was inclined to help him, so he contented himself with a life of making a public spectacle of himself. He became notorious for his foppish dress, his squalid romantic affairs, and his obsession with chess. Many strange stories were told about this strange man. After his death in 1873, “Appleton’s Journal” reported that he “lived in a great, gloomy house at the North End, and inspired a sort of dread whenever he appeared...There was a prevailing notion that he had some time done something horrible, but no two gossipers agreed on what it was. Men, almost as dark and strange as himself, were said to be seen going in and out of his house after nightfall; but no result that a curious public could ever discover ever came out of these secret conclaves.” Brunswick was just as addicted to litigation as Gregory: he was known to have sued a washerwoman over seven francs.

In short, he and the publisher of “The Satirist” were just made for each other. In almost no time, the ex-duke took pride of place in the newspaper’s shooting gallery. Gregory gleefully detailed Brunswick’s “unkindly and undignified” habits, his dissolute activities, and his predilection for welshing on debts. By 1843, matters had reached the point where the pair had no less than three simultaneous lawsuits against each other. Originally, Brunswick was merely charging Gregory with libel. Then, “The Satirist” implicated the duke in the then-notorious murder of a prostitute named Eliza Grinwood.

Rather unwisely, Gregory took this precise moment to launch a career as a Shakespearean actor. (You may not be surprised to learn that “The Satirist” gave him rave reviews.) In February 1843, he appeared as Hamlet at Covent Garden. To no one’s surprise, his vast number of enemies saw their splendid chance for revenge. On opening night, the minute Gregory appeared on stage, the audience began to riot. The demonstration was so noisy and violent the producers had no choice but to abort the performance.

Gregory was convinced that Brunswick was responsible. “The Satirist” accused the duke of hiring “the filth of St. Giles” to attack “a man whose great weight of offence is SPEAKING THE TRUTH, AND EXPOSING THE VICES AND CRIMES OF SOCIETY.” However, the editorial declared, Gregory would rise above “the petty machinations of a ‘super-annuated’ twaddler, who appeared to derive gratification from his own intemperance of folly, and the spleen of vindictive feeling.” And, naturally, he sued Brunswick for that opening-night debacle.

The judge overseeing that suit agreed that the theater audience behaved disgracefully. On the other hand, in order to prevail, Gregory had to prove that Brunswick had orchestrated the riot, which was a whole other issue. Brunswick produced many witnesses who testified that he was far from the only Londoner who hated Barnard Gregory, and none of them needed any inducement to teach him a lesson. Public sentiment about the theater demonstration was echoed by Charles Dickens, who commented to John Forster that “I begin to have hopes of the regeneration of mankind after the reception of Gregory last night.” It was later claimed that the judge himself praised those who had disrupted Gregory’s performance as showing “public spirit.” Whether this story is apocryphal or not, the jury shared in that sentiment. Brunswick was acquitted.

Round Two in the Gregory/Brunswick legal fight was the duke’s libel suit regarding “The Satirist’s” allegations regarding the Grimwood murder. This could hardly be called a battle at all. On day one, Gregory’s lawyers told the court he had withdrawn his “not guilty” plea. While Gregory denied naming the duke as the murderer, he acknowledged that what he had printed was meant to damage Brunswick’s reputation.

For this indiscretion, Gregory received a year in Newgate. (“The Satirist” responded to the verdict by printing a curious editorial arguing that while Gregory’s allegations against Brunswick may have been, according to “the late odious and detestable Law of Libel,” legally libelous, that did not necessarily make them untruthful.)

At the time of his imprisonment, Gregory had no less than eleven other libel suits pending against him. After his release, the publisher, pleading ill-health, managed to get them deferred for several years. “Whom,” his newspaper thundered, “do they hope to crush? A man once of great talent and indomitable energy, but now enfeebled, borne down, emaciated by prison fare, prison discipline, prison constraints, and prison cruelties!” In the meantime, yet another Brunswick-related lawsuit bubbled up, over “The Satirist” hinting that the duke and convicted murderer Thomas Hocker had indulged in “certain practices which cannot be named.” The jury--perhaps unconvinced of the falsity of these allegations--gave the verdict to the duke, but awarded him damages of just one farthing.

In 1845, Gregory tried reviving his Shakespearean career, only to meet heckling and howling audiences wherever he went. (This was arguably an injustice, as the few impartial observers felt he had genuine acting ability.) Gregory responded with a pamphlet arguing that he was being punished for sins of the past: he claimed his publishing days ended when he was imprisoned in 1843, so denying him the chance to follow a career on the stage was nothing less than persecution by “the moral refuse of the metropolis.” Whatever else he may have been, Gregory was a fighter. Despite these setbacks, he made a well-received appearance as Richard III at the Strand Theatre (the audience may have seen it as typecasting,) and wrote two successful plays.

In December 1849, “The Satirist” finally met its ignominious end when its new publisher, Martin Hansill, was convicted for helping a woman extort money from a rich businessman from Twickenham. It was said the Duke of Brunswick had persuaded the government to finally suppress the newspaper, but by this point, the publication probably needed little help to go under.

Gregory continued on his true career: litigation. He sued one Margaret Thompson over the terms of her uncle’s will. This lawsuit was happily resolved when, in March 1847, he and Thompson married. Gregory had managed to save a good deal of his ill-gotten gains, and as Thompson had money in her own right, the pair lived very comfortably. In contrast to his sordid professional career, in his personal life, Gregory had many friends, who described him as friendly, well-mannered, and highly amusing. His dinner parties were particularly popular. He seems to have lived a quiet and contented existence until his death from lung disease in 1852.

|

| "The Witches' Cove," Follower of Jan Mandijn |

The Strange Company HQ kitchen staff will be serving lunch with this week's Link Dump!

What the hell is the Upton Chamber?

The spooky lore of Lucedio Abbey.

Eva Peron's secret lobotomy.

A look at "The Consolation of Philosophy."

A look at a new biography of Longfellow.

Deciphering a 17th century codebreaker.

The WWII mystery of Shingle Street.

The lore surrounding a Texas shipwreck.

The European roots of the Headless Horseman.

An accused witch and a prison extortion racket.

Contemporary reviews of Du Maurier's "Rebecca."

Evidence of amazingly old Neanderthal cave constructions.

Analyzing when and why Americans lost their British accents.

Why mosquitoes like our blood. (Considering I've just gone through a very itchy summer, my answer is: because they are all Satan's emissaries.

Marriage announcements in the old newspapers.

For just 31 million bucks, you could've bought your very own T. Rex.

It seems that our minds are much more than our brains.

Some early black British sporting heroes.

Uncovering an early medieval cemetery in Germany.

A ghost visits a wake.

The art of the Olmecs.

Why you shouldn't shoplift from Pompeii.

Catherine of Aragon goes to war.

A new theory about the Tunguska Event.

The prelude to the battle of Hastings.

The watch cat of the Brooklyn Bridge.

The tomb of the real "Maid Marian."

Video of a dying star.

The bizarre tragedy of Blanche Monnier.

The first professional female jazz drummer.

Taking UFOs seriously.

Contemporary criticism of Plymouth Colony.

Birds show sympathy to others.

How Margaret Catchpole came to be transported to Australia.

This week in Russian Weird looks at an...unexpected coloring book.

The murder of a 14th century bishop.

California's first poet laureate.

A prehistoric journey revealed in footprints.

The position of wives in 18th century English law.

A young woman's very weird disappearance.

The season of the body snatchers.

Mary Toft, famed rabbit mom.

The Bronte Country during WWII.

So there's a guy with a jetpack flying around LAX.

The slaves who fought for the British during the American War of Independence.

The history of HMS Dido.

How a saintly king lost his shirt.

The life of a WWI nurse.

Remembering the Frost Fairs.

Custer's other "Last Stand."

That's a wrap for this week! See you on Monday, when we'll look at one of England's most scandalous newspapers. In the meantime, here's some Handel.

|

| Via Newspapers.com |

A mystical cat who loves beer, enjoys fine dramatic works, and hates the news media. You bet I’m inviting him into the hallowed halls of Strange Company HQ. The “San Francisco Chronicle,” October 13, 1899:

The Baldwin Theater possesses a very peculiar black cat who has probably received more attentions from dramatic celebrities male and female than any member of the feline tribe in the country. Selim is the name of the highly cultivated mouser, the title having been bestowed on him by some discriminating actor who was doubtless impressed by the rather Oriental tastes of the sable pet. Exactly how or when Selim became one of the properties of the theater no one can tell. All at once he sprang into notice and favor as a habitue of the greenroom and the stage and soon made himself as much a feature of the establishment as anything with four legs and a mercurial disposition can possibly be. When the Fanny Davenport combination occupied the theater recently, Selim attracted unusual attention in the greenroom, as there were several confirmed spiritualists in the company who hold the Pythagorean doctrine of the transmigration of souls.

John Thompson, who can Impose spiritual activity into any inanimate object from a doughnut to a chunk of coal, and bring a fusillade of raps out of an ordinary piece of furniture, pronounced Selim at first sight a reanimated actor.

Property Master Marcus, who was listening to Thespian Thompson’s diagnosis, suggested that possibly Selim was the shadow of some snide song and dance man.

“In sooth thou speakest well, good Marcus,” quoth the Thespian, “but we shall soon test the temper of his former dramatic ability,” and forthwith Mr. Thompson hurled at the defenseless cat a chunk of Shakesperian blank verse that would have staggered Joe McAullife if it hit him anywhere within the scope of his intellectuality. Instead of rolling over and dying instantly, the wonderful cat faced the poetic avalanche as calmly as a duck would an April shower, and when Mr. Thompson, at the end of his declamation, fell exhausted and perspiring over the prompter’s table, Selim was as calm as Eve.

“My life upon it,” exclaimed Mr. Thompson as soon as he could collect the remnants of his breath, “Selim was a legitimate actor.”

Selim, who was listening gravely, was plainly seen by Mr. Bouvier to nod his head approvingly, and in the general discussion that followed in the greenroom the conclusions were reached that Selim was certainly the spirit of some eminent actor who once strode the Baldwin stage.

Morris Peyser thought that Selim’s appreciation of tragedy indicated that he might be the ghost of the talented William E. Sheridan, but Master Mechanic Abrahams was ready to make affidavits that the weird feline was none other than Frank Evan Rae, the Beau Brummel of the melodramatic stage.

“Why, one day when Margaret Mather put a pink ribbon round her neck, I saw him go up to the mirror and tie it into an elaborate bow with his forepaws,” said Mr. Abrahams.

Whatever the former status of Selim may have been, his future in cat life at least is assured, for his position in the theater is as well defined as that of Manager Hayman himself. Selim is the stock pet and any spare affection which the actresses have to bestow goes to him. Fanny Davenport during her recent engagement never tired of caressing Selim and the cat’s gallantry toward her was tireless. He met the actress every evening at the stage entrance and greeted her with a cordial purr and after receiving the expected caress, trotted after her to the door of her dressing-room where he left her with a respectful “meaow.” While the star was on the stage Selim stood on the first entrance watching her with evident interest and wagging his tail cheerfully whenever the auditorium echoed with appreciative applause.

The fourth act of “La Tosca,” where Scarpia presses his unwelcome attentions on the heroine, affected Selim in an unusual manner, but his emotions have so far overcome his regard for stage etiquette as to lead him to dash from the wings on the stage and aid the actress in her struggles with the athletic Scarpia.

That Selim is a cat of the most extraordinary kind was shown by his conquest of Frank Willard, Miss Davenport’s stage manager. When the Davenport combination occupied the theater Assistant Treasurer Peyster called Willard’s attention to the fact that Selim was regarded as something supernatural. Mr. Willard, who is quite a connoisseur in cats and a skeptic of the strongest type, smiled at the story, but before two days he was a firmer believer than anybody in the superstition about Selim. The phenomenal intelligence of the stage pet so impressed Mr. Willard that Selim got more privileges than were granted to the most favored bipeds of the company. The unheard of liberty of sitting on the prompt table during rehearsals was allowed Selim, and in the fourth act he was permitted to occupy the first entrance without drawing forth the vigorous reprimand that such a crime calls forth when a human biped is the offender.

Miss Davenport at the close of her recent engagement presented Selim with an expensive jeweled collar in presence of the full company.

The only person around the Baldwin Theater who discredits the superstition that Selim is the reincarnation of some actor’s spirit is Forrest Seabury, who will have it that the wonderful cat is some departed scene-painter. Whenever Selim is not engaged downstairs he wanders up to the paint frame and sits for hours at a time watching the pictorial work with an interest that is altogether unfeline.

Selim’s almost insane antipathy to the attaches of snide dramatic sheets shows, however, that artist Seabury is wrong and that the wonderful cat is imbued with the soul of a true actor.

Selim knows every offensive scribbler by sight, and when he catches a glimpse of them behind the scenes flies into an ungovernable rage. His form swells to gigantic proportions, his sleek back becomes corrugated, and the bristles on his inflamed tail stand out like spikes on a telegraph pole. His eyes blaze with fury and his whole aspect denotes the progress of a regular whirlwind of passion. If the intruders ask for an interview with the star who may be playing, Selim’s rage finds expression in whines and howls which Charley, the doorkeeper, interprets into such words as “blackmail,” “scurrility,” etc. It is evident that whatever branch of the dramatic art Selim followed in his former life, he learned to hate the newspaper scribes cordially, and when he displays his feelings toward them most of them are inclined to beat a hasty retreat.

Though apparently well advanced in years Selim has all the true Thespian’s admiration of the opposite sex, and his four-footed female admirers are numerous; whenever he wants to show his partiality toward some sleek dame of his tribe he introduces her behind the scenes, and during the Davenport engagement appeared to be so beset with applications for free passes that Doorkeeper Charley had to repress the crowd with a club. In every other respect but his blind infatuation for the other sex Selim is a most exemplary cat, and though he can chew tobacco like a forty-niner and drink beer he never carries these habits to excess. His gallantry, however, occasionally scandalizes the staid members of the company, but Manager Haymond overlooks all Selim’s moral obliquities, believing that he is a mascot of the most pronounced type. Doorkeeper Charley has orders to keep Selim supplied with delicate cutlets of liver when the ordinary forage of the theater, such as rats, mice, and cockroaches runs low. Another of the doorkeeper’s duties is to groom Selim once a week, but the post of tonsorial manipulator of the cat’s whiskers is a sinecure, as the ladies of the ballet are constantly titivating Selim and bestowing their affections on him in a way that would drive the bald-headed holders of front seats wild with envy.

The latest rumor round the Baldwin Theater about Selim is that Mr. Bouvier, who is quite a playwright, is constructing a drama with Selim as one of the leading characters. Selim is the pet of the heroine, who is restrained by hard-hearted parents from visiting her unfortunate lover, who is incarcerated in the fourth story of a Bush street boarding-house for non-payment of dues. Selim, to please his fond mistress, defies a ferocious bull-terrier in the backyard of the hashery, and scaling to the bedroom of the imprisoned lover with a clothesline wound round his tail, sets the captive free. In the last scene the happily wedded pair are shown by the domestic hearth, surrounded by thirteen beautiful children, while Selim grown old and gray, but still as joyous and talented as ever, sits on the window-sill and sings “Auld Lang Syne.”

It is thought that this will cap the climax in the way of pure and emotional domestic dramas.

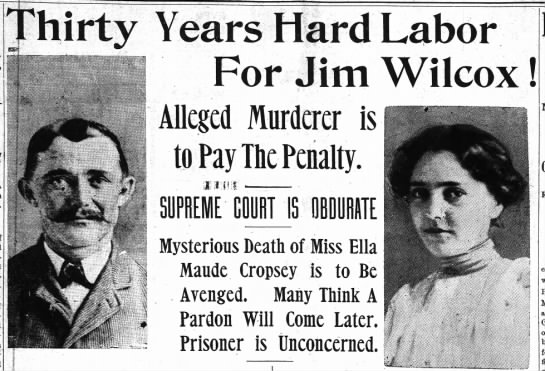

Ella Maude “Nell” Cropsey is romantically remembered as “Beautiful Nell,” even though her surviving photos suggest someone of no more than average attractions. (A contemporary once bluntly described her as “plain.”) Whether the sobriquet was deserved or not, it illustrates how her enigmatic end has obtained a lasting legendary status in the area where she spent the last few years of her life. After all, as Poe famously wrote, “the death, then, of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.”

Nell Cropsey was born in Brooklyn, but in 1898, her family moved to Elizabeth City, North Carolina, in order to take up farming. Before long, the seventeen year old girl was courted by a young man named Jim Wilcox.

Unfortunately, we don’t know very much about Wilcox as a person. Although legend has it that Jim was considered a strange young man, that may well be apocryphal. One gets the impression that he was an ordinary, decent enough fellow who, in normal circumstances, would pass through life essentially unnoticed.

Jim and Nell’s romance did not remain a happy one. By the time they had courted for three years, trouble began to develop. Nell, it was said, began openly flirting with other men, and she frequently treated Wilcox with indifference, or even outright rudeness. Jim, according to his later story, resolved to end this increasingly acrimonious relationship.

Such was the uneasy state of affairs on the evening of November 20, 1901, when Wilcox arrived at the Cropsey home.

Nell and Jim sat in the parlor with her sister Olive (known as “Ollie,”) a visiting cousin, Carrie Cropsey, and Ollie’s beau, Roy Crawford. They spent the evening in the way all playful young people have done from time immemorial, by...uh, discussing their favorite methods of committing suicide.

Jim declared that he would choose to drown himself. “Oh, I wouldn’t,” Nell chirped. “I’d rather freeze to death.”

By about 11 p.m., Jim decided he had had enough of this cheery banter, and rose to leave. According to Ollie, as Jim was exiting, he stopped and whispered to Nell that he wanted to speak to her. Nell looked back questioningly at her sister, who nodded her assent.

Now we come to one of the many disputed points in this frustratingly murky tale. Some say that as Jim and Nell stood together on the porch, they had a loud, vehement quarrel. Others say they spoke so quietly, it was impossible to overhear what they were saying. At around 11 p.m., a neighbor named Caleb Parker drove his buggy past the Cropsey home. He later said he saw two figures standing on the sidewalk, but it was too dark to say for certain who they were.

Meanwhile, inside the house, Carrie retired for the night. Roy Crawford left immediately afterward. He claimed that both Jim and Nell were gone. At 11:45, Ollie went to the porch to call Nell to come in, but got no reply. Presuming Nell had slipped back inside and gone to bed, she went up to her sister’s room. It was empty. Puzzled, a bit concerned, but not yet really alarmed, Ollie went to bed.

Around midnight, a loud commotion broke out in the Cropsey back yard. Their dogs began barking furiously, and their pigs let out anguished squeals. Ollie heard a neighbor yelling, “Cropsey! Cropsey! Someone’s after your pigs! Get your gun!”

Ollie joined her father William in the hallway. When she told him that Nell and Jim were out there somewhere, the irritated father assumed they were the cause of the disturbance. However, when William Cropsey went out to the yard, there was not a human to be seen.

When William returned to the house, he learned that Nell was still absent. It was becoming obvious that something was wrong. Mr. Cropsey stormed over to the Wilcox home and banged on the door. When Jim’s still half-asleep father answered his knocks, William demanded to see Jim. He wanted to know where his daughter was.

Mr. Wilcox was surprised. He said that Jim had been in bed since midnight. A few moments later, young Wilcox appeared, in his night clothes and looking as sleepy as his father. When William asked what had happened to Nell, Jim seemed genuinely surprised. He insisted that he had left Nell on the Cropsey front porch around 11:15. He had not seen her since.

William went straight to the home of the Police Chief. The two men searched Cropsey’s house and grounds. They searched the yards of all the neighbors. No Nell.

The pair marched back to the Wilcox home and ordered that Jim tell them exactly what the hell had happened that evening. Jim told them that at 8 p.m., he went to the Cropseys to return Nell’s photo and an umbrella she had given him. He had not planned to stay, but Ollie had urged him to spend the evening. At 11, he asked Nell to go outside to talk. He gave her the photo and umbrella and told her that all was over between them. She began to cry. He watched helplessly for a few minutes, and, wanting to escape this uncomfortable scene, he said he had to meet a man. Nell stopped weeping long enough to snap, “Well, go on then!”

Jim left. Naturally upset by what had just happened, he walked aimlessly for a short time--maybe half an hour--encountering a friend, Leonard Owens, along the way. The two chatted for a few minutes. (Owens confirmed that this meeting took place.) Wilcox went to a bar and had a beer. And then he went home.

The Police Chief did indeed find the umbrella at the Cropsey home, but Nell’s photo was missing. He decided the best thing to do would be take Jim into custody until the mystery of the girl’s disappearance was cleared up. This proved to be no easy task. Bloodhounds followed Nell’s trail from the porch to the Cropsey summerhouse, and then to their boathouse. No further. The river was dragged, and virtually every home in and around Elizabeth City was searched. No sign of Nell was found.

It never pays to be the last known person to see someone who has mysteriously vanished. It rapidly became the near-universal opinion that Jim Wilcox, in some still-unknown way, was responsible for Nell’s disappearance. He was formally charged with abduction, but until Nell--or her body--reappeared, the case remained at a standstill.

Jim was repeatedly questioned, but he stuck to his initial story. Meanwhile, the usual number of “sightings” poured in. People came forward claiming to have seen Nell all over North Carolina.

On December 24, William Cropsy received an anonymous letter postmarked Utica, NY. The author claimed to know what had happened to Nell. According to this writer, Jim Wilcox left Nell crying on the porch. She stood there for some time, until she heard the family dogs barking. When she went to the back yard to investigate, she found a man she knew stealing a pig. When she threatened to tell her father, the man knocked her out with a stick, carried her to the river, dumped her in a boat, and rowed away with her. The writer had no idea if she was alive or dead at that point. This man was named in the letter, but his identity was never publicly revealed.

This informant went on to say that her body would be found at a certain point in the river. He/She even included a helpful diagram of the spot. It was 150 yards from the Cropsey boathouse. Very oddly, Cropsey seems to have ignored the letter, not even bothering to tell the police.

His indifference became even stranger when five days later, fishermen found Nell’s body in the exact place indicated by the anonymous writer. Presuming she had died on the night she was last seen, it was noted that her corpse was unusually well-preserved. It was also considered strange that the site where she was found had been repeatedly searched.

When word swept through the town that Nell had finally been found, the police had a very hard time saving Jim Wilcox from a date with a lynch mob. It took surrounding the jail with the State Guard for the would-be assassins to finally disperse.

Once the public decides someone is a murderer, it is easy for them to find “proof” of the charge. Evidence began mounting pointing to Wilcox’s guilt, but unfortunately, a lot of it was of questionable veracity, and all of it circumstantial. It began to be said that, in fact, Nell had been the one to break off their romance. It was claimed that, a few days before Nell vanished, Jim had tried to get her to go sailing with him (cue ominous music) but Nell was afraid to be on a boat with him, and declined. He then took Carrie Cropsey and another of Nell’s sisters out on his boat. Just before the trio returned to the house, it was claimed that Jim, as a “joke,” suggested wrapping one of the girls in a blanket and carrying her into the house, as if she were dead.

The coroner came to the somewhat mystifying conclusion that Nell had died as the result of “being stricken a blow on the left temple and by being drowned in the Pasquotank river.” However, no water was found in her lungs. Medical experts never did agree if she died from being hit on her head or from drowning. The blow, it was determined, had been caused by a padded instrument, like a blackjack.

The authorities decided that all of this was enough to justify putting Wilcox on trial for murder. It was a very hard job to get twelve men willing to say they had not already made up their minds about the defendant’s guilt. Meanwhile, the same unknown person who had written to William Cropsey sent another letter to Jim Wilcox’s father. This informant continued to insist that Jim was innocent, giving the same account of Nell’s death given in the previous letter. The alleged real murderer was, according to the newspapers, “familiar to all Elizabeth City people.”

|

| "The North Carolinian," February 5, 1903, via Newspapers.com |

The prosecution argued that Wilcox was the only one to have the means and opportunity to kill the girl. As for motive, they claimed that Wilcox wanted to dump Nell, but feared the resulting scandal. They described Nell as a “happy, healthy girl” who had no reason to kill herself. They produced medical witnesses who testified that Nell was already dead when she entered the river. In response, all the defense could do was insist that Wilcox had no idea how Nell had died, and they suggested that, distraught at being jilted, she had drowned herself. Wilcox himself did not take the stand.

While the jury deliberated, there were numerous reports that if Wilcox was found not guilty, he would be kidnapped from jail and lynched. It was even suggested that the jurors themselves would be in grave danger if they did not return the approved verdict. To no one’s real surprise, the jury voted for a conviction, and Wilcox was sentenced to death. However, his lawyers, citing the extreme prejudice against their client in Elizabeth City, were able to win him a new trial in another county. Wilcox was again found guilty, but this time merely for second-degree murder. His life was spared, but he faced a long prison term. As he was heading to the penitentiary, Wilcox told a policeman, “There is a little fire smoldering in Elizabeth City which might break out in three months, or it may be three years, but it will break out sooner or later, when the truth will be known which would then relieve me of the burden of somebody else’s sin.”

|

| "The Tar Heel," June 12, 1903 |

Wilcox was in the state prison until December 20, 1920, when the Governor, Thomas Bickett, granted him a pardon. As three earlier attempts to pardon Wilcox had failed, Bickett’s change of heart remains a mystery. Roland Beasley, a long-time North Carolina newspaper man, stated that Wilcox had told the Governor something which convinced Bickett of his innocence. Beasley said that before Wilcox was pardoned, Bickett told him that there was an explanation of Nell’s death which would exonerate Wilcox. The Governor added that he was going to talk to the prisoner in person, and “If he says what I think he probably will say, I expect to pardon him.” Unfortunately, it was unrecorded why Bickett came to believe Wilcox was not guilty.

Wilcox was no longer a prisoner, but it is a stretch to say he became a free man. He spent his life living as a hermit in the woods. He once explained that he knew nobody wanted him around. He became destitute, sick, despondent, and usually drunk. To the few people who would talk to him, he continued to insist he was entirely innocent of Nell’s murder. He added that he was certain that William Cropsey knew who had killed her. After fourteen years of this bleak existence, he finally had enough. In December 1934, he took a shotgun and blew off most of his head.

To this day, people in Elizabeth City ponder the riddle of Nell Cropsey’s death. Among the residents obsessed with the mystery was one William E. Dunstan. In his book “Nell Cropsey and Jim Wilcox: The Chill of Destiny,” he gathered together local recollection and gossip to put together his scenario of what actually happened on that long-ago November night.

According to this version of events, Nell had secretly been having an affair with a married neighbor, John Fearing. Her “romance” with Wilcox was merely a cover for this illicit relationship. After Jim returned Nell’s photo and umbrella, he left, leaving her standing on the porch. After Wilcox’s departure, Fearing, who had been concealing himself nearby, approached Nell. As the two passionately kissed, William Cropsey--who was known to have a violent temper--came outside. Enraged by his daughter’s unmaidenly behavior, he impulsively hit her. Unfortunately, the blow was so violent he accidentally killed her. Cropsey and Fearing were equally horrified by this sudden death, and equally anxious for a cover-up. Both their reputations would be ruined if the truth came out. With the possible aid of Ollie, Roy Crawford, and Nell’s brother Will, the girl’s body was concealed in the family icehouse until they could decide what to do with her. A plot was hatched to make Jim Wilcox the fall guy. Although there is no way to prove this is what really happened, it would explain some of the oddities surrounding Nell’s death, such as the striking lack of decomposition and the fact that she had been found at a spot which had been previously searched.

Dunstan suggests that it was this dark deed which led to the subsequent tragedies which plagued the Cropseys. Both Roy Crawford and Will Cropsey eventually committed suicide, and Ollie ended her days as a recluse, troubled, it was said, by mental instability. Nell, it seemed, haunted everyone who had been close to her.

If Dunstan’s reconstruction is at all correct, Nell Cropsey’s death was no average accident or murder, but an epic Southern Gothic tragedy.