|

| The Western Spirit, October 11, 1912, via Newspapers.com |

When you think of bleak, mysterious murders with a Gothic hue, a small town in early 20th century Kansas is not the first thing that springs to mind. Neither is a postmaster, for that matter.

Well, think again.

We do not know very much about the life of George McElheny of Louisburg, Kansas (population 500,) because there wasn’t very much to say. He was the town’s postmaster, which suggests he was a man of some local standing and respectability. He gave the impression of being a classic “ordinary citizen”; someone who quietly lives their life without distinguishing themselves in either a positive or negative fashion.

On the evening of October 5, 1912, the 32-year-old McElheny, along with his wife Maude and their two young children, Victor and Winifred, attended a band concert. After they returned home, George went to the kitchen of their little cottage to adjust an oil lamp, while his wife went to another room to take off her wraps. All was quiet. Then, around 10 p.m., someone silently walked up to the screen door of the kitchen and shot McElheny through the screen, killing him almost instantly. The assassin then vanished into the night. Although the screams of McElheny’s wife and children sent neighbors instantly rushing to the scene, no one saw any sign of the murderer.

This was one of those murders that left authorities in an instant state of befuddlement. Literally no one had any idea why anyone would murder McElheny in such a cold, execution-style fashion. Robbery was clearly not the motive, and the dead man was a churchgoing, friendly sort with no enemies. His marriage of twelve years was believed to have been a happy one.

The first thing police did was to bring in bloodhounds, in the hope they could find the killer’s trail. Three hundred men, virtually the entire male population of Louisburg, was summoned. They all stood in line to be inspected by the dogs. The hounds took little notice of any of them. The dogs followed a trail which led to a circuitous route for a half-mile to the train depot. The dogs refused to go any further.

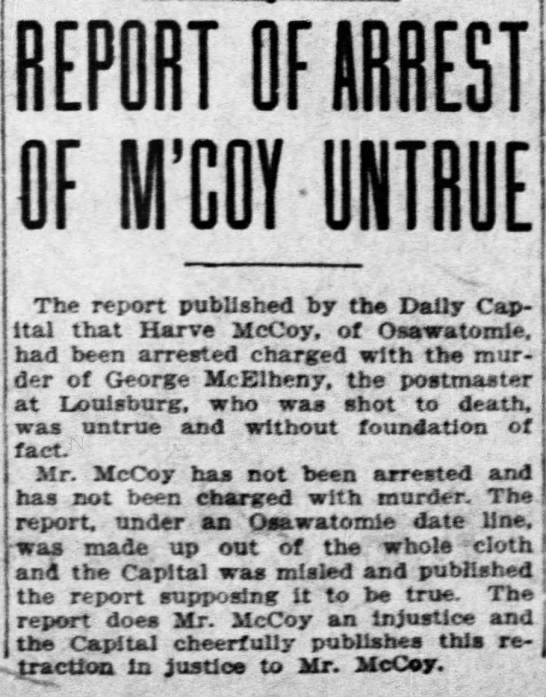

Lacking any workable clues, the press then did what it usually does in such situations: bring on the usual suspects. The first to be named was a laborer for the Missouri Pacific named Harvey McCoy, on the grounds that it was said McCoy had quarreled with McElheny over the laborer’s desire to sell bootleg whisky at the Louisburg fair. (McElheny was the fair’s treasurer.) It was alleged that McCoy had recently bought a box of gun shells similar to the shell found at the murder scene. Newspapers soon reported that McCoy had been arrested and charged with the slaying.

And then, the newspapers had one of those “Oopsie!” moments which make libel lawyers throw their hats in the air and emit three cheers:

|

| Topeka Daily Capital, October 13, 1912 |

Exit Mr. McCoy from our little story. (And, yes, he sued several different newspapers and one Keith Clevenger for defamation.)

A local “citizens committee” offered a reward of $1,000 for any information leading to the arrest and conviction of this peculiarly mysterious murderer. No one came forward.

Lacking any sort of clues to follow, the story quickly died in the newspapers. On October 31, it was reported that one William Henson had bought the late McElheny’s bird dog, “considered by sportsmen as one of the best ones in this part of the country,” for $15.

It was looking as if this sporting dog would be the last word on the murder. Then, in late December, the inquest into McElheny’s death was held, and things quickly got interesting. This hearing had been held in secret, with the jury hearing from a variety of witnesses behind closed doors. This testimony apparently consisted entirely of gossip and innuendo, but it was enough to have one Charles H. Crosley accused of the murder.

The 60-year-old Crosley had been considered one of Louisburg’s most respected citizens. From what was reported, the case against him was laughably feeble. Several days after the murder, one person told another that Crosley had said he would “kill someone.” This alleged statement circulated through the town until, inevitably, McElheny’s name was inserted as the “someone.” Shortly after the murder, it was rumored that Crosley had a pair of shoes in no need of repair, but he had taken them to be “half-soled,” anyway. Was this to prevent the shoes being fitted into the tracks left by the murderer? (Sadly for the gossips, testimony from Crosley’s shoemaker established the innocence of Crosley’s act.)

Crosley himself issued a signed statement. It made a convincing case for his innocence:

I did not kill George V. McElheny. I had no reason to do so. He was one of my best friends. If I had sufficient reason to kill him or any other man I would have done so in daylight and there would have been no need for any detectives. I welcome arrest because I have sufficient evidence to show that I could not possibly have committed the crime. George was killed at about 9:45 o'clock in the evening. I can prove that I reached my home at 9:30 o'clock and was playing solitaire when the shot was fired. A relative of the dead man was at my house at the time and another relative talked with me over the telephone ten minutes before the murder. My house is nearly a mile from the McElheny home. Another thing, I have not owned a shotgun for more than twenty five years and I have not fired one in five years. I never have borrowed one. I have obtained denials from two persons whose statements are said to have led to this slander and gossip and I am more than willing to face any man who has anything upon which to connect me with this murder.McElheny’s relatives, including his widow, asserted their belief that Crosley had nothing to do with the murder.

The secret inquest went on. And on. And on. It was now alleged that for weeks, McElheny had lived in fear of being attacked, but by whom? And why? Nobody knew. Investigation into his professional and private life revealed no reason for anyone to want him dead.

On January 7, the inquest finally adjourned, without hearing anything the least bit useful. The jury gave the standard verdict of murder by person or persons unknown. President Wilson appointed Mrs. McElheny to succeed her late husband as postmaster. And life went on.

It looked as if the investigation into the murder was as dead as McElheny himself. Then, in April 1915, came a development absolutely no one had predicted: Maude McElheny went to the Miami county prosecutor and told a tale outdoing the most lurid dime novels of the period.

Mrs. McElheny claimed that before her husband’s death, one Roscoe Hornbaker had written to George suggesting they indulge in a spot of wife-swapping. When McElheny declined, Hornbaker “forced his attentions” on her. She was never a willing partner in the affair, but she continued to sleep with him because he threatened to tell her husband about their relations if she refused him. He also tormented her with allegations of George’s infidelity. Hornbaker told her that George was having an affair with Charles Crosley’s daughter Zelda (who worked in McElheny’s post office) and was planning to elope with her, taking George’s son Victor with them. (Maude explained that Zelda liked their son, but not their daughter.)

Hornbaker subsequently urged her to kill George by putting ground glass in his food. Once George was dead, Roscoe would murder his own spouse, and then the two of them could be together. When she refused, Hornbaker took matters into his own hands by hiring a hit man to shoot his rival. (She learned of Hornbaker’s guilt in a dream, in which her husband appeared at her bedside and named Roscoe as the man who had him killed.) She explained her long silence about all these fascinating details by saying Hornbaker had threatened to kill her as well if she told anyone.

Hornbaker, a 39-year-old mail carrier from the office where George McElheny had been postmaster, was immediately arrested. He vigorously denied every word of Maude’s story. “It is a frame-up!” he declared. He had never been intimate with Mrs. McElheny, he knew nothing about the murder, and he had no idea whatsoever why the widow would accuse an entirely innocent man. He added that he could prove he was at home with his family at the time of the murder. (As a side note, many people commented that it seemed unlikely that in a nosy and gossipy community like Louisburg, such a liaison could go unnoticed.)

The statement of Hornbaker’s wife Belle took the mystery’s weirdness quotient up by quite a few notches:

Mrs. McElheny never was in any room of my house alone with my husband. I do not think she ever was alone with him anywhere. I am sure there was no love affair between them. My husband has always been good to me, much better than most husbands and we had a perfectly happy married life. He never had an affair with that woman, of that I am sure.Hornbaker was a liked and well-respected member of the community, so his arrest came as a general shock. What was even more startling was that there was at least some corroboration for Mrs. McElheny’s scandalous story. At Hornbaker’s trial, Dr. F.J.V. Ferrel, coroner of Miami county at the time of the murder, testified that the defendant had repeatedly urged him to call off the investigation into McElheny’s death. After first denying that he had letters from Mrs. McElheny, he finally admitted that he did, and reluctantly agreed to give them to Ferrel. He then continued to pester the coroner, asking if “Maude had told anything,” and if she would “keep still.”

Why she is accusing him I don't know. But she has some motive. She came to my house on the 19th day of last March and talked with me in a friendly manner for a few minutes. Then she said, “Are you alone?” I said I was. “I want my letters,'' she cried.

She was sitting behind me and as I turned my head, astonished at her words, she had a revolver pointing at my head. I jumped up and caught it and threw it up. See where I bent my thimble in the scuffle. I feel sure she was going to kill me. Never did I see such a look In a human being's eyes as was in hers. I knew I was fighting for life. I tried to get her out of the door but was not strong enough and at last I got near the entrance myself and slipped out and hanged the door. I ran for my life to my neighbor, Mrs. John Rice's, and told her what had happened. Mrs. McElheny followed me out of my house and Mrs. Rico saw her.

These letters were introduced into the court record. They were described as “tangled and incoherent missives,” indicating that Maude hated and feared Hornbaker, and she repeatedly begged him to leave her alone.

Maude’s testimony was a repetition of her initial confession. The “unusually attractive” young woman was obviously extremely nervous on the stand, telling her story in a halting manner, with her eyes continually downcast.

|

| Topeka Daily Capital, April 3, 1915 |

Hornbaker’s attorney opened the defense by asking Mrs. McElheny point-blank if it wasn’t true that she herself shot her husband. He pointed out that she testified that she had been in the front yard to collect a milk delivery just seconds before the shooting. “Did you take George’s shotgun with you when you went out after that milk,” he thundered. “Did you go around to the kitchen door to shoot him, then run back and come in by the front way?”

The shaking, white-faced woman stammered out a denial.

Evidence exonerating Hornbaker for the murder was given by a Louisburg telephone operator, Edgar Hand. He testified that on the night of the murder, Mrs. McElheny phoned to tell him of the tragedy. He then called Hornbaker, who instantly answered the phone. Hand noted that Hornbaker’s home was a considerable distance from McElheny’s.

The defense continued to suggest that Maude was the real murderer. Hornbaker took the stand, still denying Maude’s story in its entirety. He stated that his reason for talking about Mrs. McElheny after the murder was that in 1912, George had given him several notes he had found hidden in his home. They were love letters Maude had written to a fellow postal service employee named Alf Moody. These letters naturally concerned George, and he asked his good friend Roscoe to put them in safe-keeping for him. (Hornbaker added that he himself had once caught Maude and Moody getting frisky in a back room of the post office.) Hornbaker claimed that following the murder, Maude learned he had the letters. When he refused her demands to give them to her, she threatened to implicate him in George’s death. As for his alibi, his wife and children testified that he was at home all the night of the murder.

After all the testimony had been heard, the judge told the jury they had two choices: return a verdict of first-degree murder, or acquit the prisoner. He advised them that circumstantial evidence was not enough for a conviction, and warned them against believing implicitly all the witnesses. As nearly the entire case against Hornbaker was circumstantial, this was believed to be very good news for the defendant.

And so it was. On June 24, 1915, after two and a half hours of deliberation, the jury delivered an acquittal. After the verdict was read, Hornbaker told the reporters that although as a result of the trial, he had lost his job and was forced to mortgage his home, he fully intended to return to Louisburg and start over. That appears to have been exactly what he did. He remained in Louisburg until his death in 1945. Maude McElheny remained Louisburg's postmaster until at least 1923. Chance encounters around town between those two must have been...awkward. Maude married two more times before she died in California in 1960.

So. If Maude McElheny was telling the truth, Roscoe Hornbaker, our humble little small-town mail carrier, was a villain who could have taught the worst of the Borgias a thing or two. If Hornbaker was telling an honest tale, Mrs. McElheny was a psycho straight out of “Fatal Attraction.” Or were there elements of truth and falsehood in both their stories?

In any case, it’s quite startling to browse the old newspapers and stumble across a small Kansas town which would be right at home on “Midsomer Murders.”

[Note: In January 1916, John Bush, a farmer living eight miles northwest of Salina, Kansas, was murdered under circumstances eerily similar to McElheny’s. One evening, as he sat at his kitchen table reading a newspaper, a gun blast fired through a window killed him instantly. Nine months later, a farmer named William Patterson, who lived about three miles from Louisburg, was slain in an identical fashion. Reading newspaper at kitchen table. Gunshot through the window. Dead. Neither killing was ever solved.

Could there be a connection between these three odd--and oddly alike--murders? Unfortunately, that question is fated to remain forever unanswered.]

Hornbaker certainly had a convincing tale to explain the letters he had and that Maude wanted back. One assumes that Alf Moody could not be found to corroborate or deny anything. From the evidence given, I would tend to believe Hornbaker over Maude, but the two subsequent murders suggest a third party, crazier than anyone called as a witness at this trial!

ReplyDeleteMoody, unsurprisingly, denied having an affair with Maude. It's anyone's guess whether he was telling the truth or not.

DeleteRoscoe Hornbaker - what a great name!

ReplyDelete