|

| "New York Daily News," September 20, 1959, via Newspapers.com |

Q: What do you get when you mix auto theft, disappearances, amnesia, murder, and far too many tattoos?

A: One of the crazier true crime cases I’ve encountered.

At the center of our weird little saga is James Eugene Harrison of Indian River City, Florida. He was the owner of a successful window sash plant, happily married, a father of two young children. A perfect example of a solid middle-class citizen.

On October 7, 1958, the 32-year-old drove to Cocoa Beach, about fifteen miles away, to conduct some routine business. And promptly disappeared. When he failed to return home that night, his wife Jeanne immediately knew something was very wrong, and she phoned police. However, their investigation found no trace of Harrison.

No clues emerged regarding Harrison’s disappearance until a week later, when police in Jacksonville, about 150 miles from Indian River, found his abandoned station wagon. It had been sitting there since the morning after Harrison had last been seen. Ominously, the front seat was saturated with blood. “Somebody was murdered in that car,” a Jacksonville officer concluded. When the blood was found to match Harrison’s Type O, the natural conclusion was that the “Somebody” was the missing man. It was presumed that Harrison had been unlucky enough to pick up a hitchhiker who robbed and murdered him, then buried him in some obscure place and ditched the car. However, the only fingerprints found in the car were Harrison’s.

Poor Jeanne Harrison was naturally distraught, and at a loss what to do next. As she had no idea how to run her husband’s business, she felt she had no choice but to liquidate everything, and she and her children went to live with James’ mother in Miami. To support her children, she took a job as a receptionist while waiting in an agonizing limbo, not knowing if her husband was alive or dead.

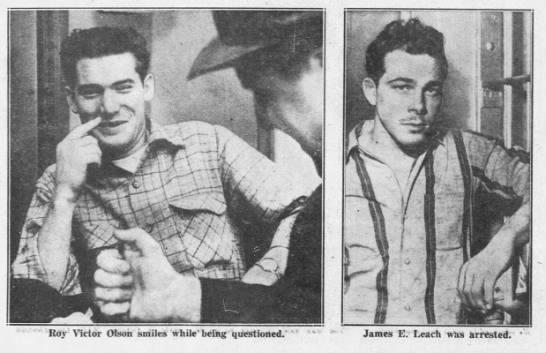

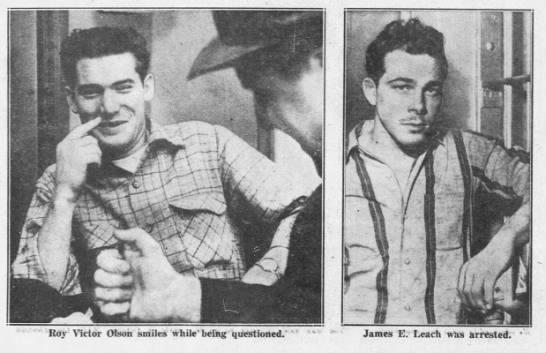

On January 18, 1959, Mrs. Harrison finally received news about James. Unfortunately, it was the worst news imaginable. A Californian named Roy Victor Olson, who had just been convicted of the murder of television announcer Ogden Miles, confessed to killing James Harrison, as well. According to Olson, before stabbing Miles he had murdered a Seattle man named John Weiler. After the Miles murder, Olson fled to Florida, where he fell in with a young Kentuckian, James Leach. The pair spent several days hitchhiking together.

Olson went on to say that on October 7, 1958, he and Leach were walking along Highway 90, between Lake City and Jacksonville, when they were picked up by a man in a station wagon. He seemed like someone who would have money on him, so when the driver stopped to stretch his legs for a few moments, the pair attacked him.

“I stabbed him while Leach stood by with a rock in his hand,” Olson told his interrogators. “We robbed him of $500. We took a shovel we found in his car, dug a grave, and put him in with his business cards. We filled it in, then drove up to Jacksonville and left the car. His name was Harrison.” Olson did not know Leach’s current whereabouts but said he shouldn’t be hard to find. “He’s just about the most tattooed fellow in the country.”

Under further questioning, Olson added more details. He and Leach covered their victim’s body with two bags of “something” they found in the car--”I think it was lime.” He described minutely the wooded area south of Jacksonville where they buried Harrison. Olson concluded with, “Well, that’s that. I wonder how many more I’ve killed?” He was, in the words of Jacksonville officer Roy Sands, “the coolest killer I’ve seen in 17 years of police work.”

Everything the police found corroborated Olson’s horrifying story. Harrison had bought two bags of fertilizer just before he disappeared. He did indeed carry a shovel in the car identical to the one described by Olson. Two fertilizer bags were found in the area where Olson said the body was buried. To wrap up this murder case, all that was needed was to find the body...and, of course, James Leach.

|

| "New York Daily News," September 20, 1959 |

The FBI issued a warrant for the tattooed Kentuckian. Florida Governor Leroy Collins sent extradition papers to California to bring Olson back to the state. On January 23, Leach was apprehended in Knoxville, Tennessee, and his captors quickly noted that Olson had not been exaggerating about his cohort’s body art. Leach had “The Kentucky Kid” tattooed on his right leg. “Six months I lived and lost,” was on his right arm. His chest sported a panther and the word “Crime.” His left shoulder read, “Born to raise Hell.” The left arm was adorned with “Born to lose,” and “Death.” His left leg featured a skull wearing a top hat.

Give Mr. Leach the prize for "Suspect least likely to be overlooked in the identification parade."

The 21-year-old Leach--who had never been found guilty of anything beyond vagrancy--protested his innocence. He admitted that he had spent a few days hitchhiking with Olson, but he had no idea the man was a murderer, and he himself certainly had no role in killing anyone. “I have no idea why he implicated me in something neither of us did,” he declared.

Given what the police had uncovered, it was small wonder no one believed him.

It was then that this seemingly straightforward murder took a bizarre twist. In Phoenix, Arizona, on the same day Leach was arrested, a well-dressed, freshly-shaved man stopped a car backing out of a residential driveway, and asked the driver to take him to the police station. This driver, understandably wary of this odd request, declined, but agreed to telephone the police to come and get the man.

The Arizona man did contact police, informing them that either a robber or a lunatic was standing in his driveway. When officers arrived, they found a man, seemingly in a great state of confusion, muttering, “How did I get here? How did I get here?”

At the station house, he informed them that he was James Eugene Harrison of Indian River City, Florida. He was stunned to find that it was January 1959, not October 1958, and had no idea at all how he came to be in Arizona.

According to Harrison, “yesterday--at least I thought it was yesterday” he was driving to Cocoa Beach. When he stopped at a traffic light, a man with a gun forced his way into the back seat. This man said, “I want to go to Jacksonville. Take me there and you won’t get hurt.” When they arrived in Jacksonville, the gunman ordered him to pull into a parking lot. After that, he said, “The lights went out.” He explained that “I woke up just a little while ago...I was lying on a parkway beside a street. My clothes were dirty and this T-shirt wasn’t mine...I never wear them. My $300 was gone. So was my watch and my Masonic ring. I found I was still wearing my wedding ring and I had 67 cents in my pocket. I started walking...I thought I was in Jacksonville…”

The police, eyeing the man’s dapper appearance, felt a bit skeptical of his story. They warned Jeanne Harrison that this Phoenix oddball was almost certainly a fraud. However, as soon as she spoke to the man on the telephone, she began screaming in joy. “It’s Jim! It’s Jim!” she cried. Still unable to believe the man’s story, investigators showed her a wire photo of the mystery man. “It’s Jim!” Jeanne insisted. “I don’t care what happened as long as he’s alive.” The ecstatic woman wired her husband the money to fly home. “It will be like starting our life all over again,” she said.

|

| "Knoxville Journal," September 25, 1959, via Newspapers.com |

Law enforcement saw their nice, tidy murder case suddenly turn into an inexplicable muddle.

Somebody had left all that blood in Harrison’s car, and, judging by the quantity of it that was found, that somebody just had to be dead. But who was this person? Did Harrison kill his carjacker? Or did his assailant attack Harrison and steal his wallet and papers, only to be murdered by Olson?

As for Olson, he now repudiated his confession, claiming that he only admitted to killing Harrison in order to get “a free trip to Florida.”

As the erstwhile murder victim enjoyed the reunion with his family, authorities began compiling a long list of questions for Harrison. His whole story struck them as, in a word, fishy. They noted that Harrison bore no signs of any injuries, old or new. Police also found it odd that he had a reddish streak in his hair that appeared to be dyed. However, his family insisted that the red spot was natural, and Harrison himself maintained that he had no memory of what had happened to him.

Harrison’s return from the dead forced police to drop the murder charges against Leach. However, they continued to investigate his confession, along with the riddle of Harrison’s disappearance. During the three months when everyone assumed he had been murdered, where was the Window Sash King, and what had he been doing? No one could say. Although his photograph was published in newspapers across the country, no one came forward claiming to have seen Harrison during the period when he was missing. When asked to take a lie detector test, Harrison declined, stating that “I’ve been pushed around enough.” He and his family went into seclusion, refusing to say any more to anyone about the whole ordeal.

On February 4, a Phoenix woman who had seen one of the published photos of Harrison contacted police. She claimed that he had been her seatmate on a bus trip from Los Angeles to Phoenix. This witness said that she had chatted with him, and he seemed perfectly rational, showing no sign of distress or confusion. The man carried no luggage with him, and left the bus in Phoenix on January 23, just a few hours before Harrison went to the police.

Frustratingly enough, there the matter rested. As far as I have been able to tell, the main questions surrounding this mystery were never resolved. Police never learned how or why Harrison vanished, or where he was for those three missing months. If--as authorities continued to suspect--Harrison knew more than he was saying, the Floridian kept his secrets to himself. The identity of the person who left all that blood in his car was fated to remain equally mysterious.

Police were able to validate at least one part of Olson’s confession: he had indeed murdered a Seattle restaurateur named John Weiler. (It was said that “perverted sex acts” figured in the stabbings of both Weiler and Ogden Miles.) He was sent to Washington state long enough to be tried and convicted, after which he was transferred to California’s Folsom Prison. In the 1970s, he was paroled, only to begin serving his 75-year sentence for the Weiler murder in Washington. In the mid-1990s, Olson--who had a religious conversion in prison and claimed to be a reformed character--was released on parole. He seems to have lived a law-abiding life until his death in 2001.

In 1960, the skeleton of a man was found near the Jacksonville Expressway, in the general area where Olson claimed to have buried his victim. It was speculated that this man--who was never identified--was the victim stabbed to death in Harrison’s car, but that, of course, was impossible to prove.

All in all, this story is like trying to put together a jigsaw puzzle when you’re missing most of the pieces.