|

| "Lafayette Journal and Courier," January 6, 1980, via Newspapers.com |

All families have their ups and downs. However, when you find a clan where an infanticide trial is arguably the least worst thing to happen to them, it’s safe to say you’ve found one very special household.

The Mabbitts--described by one newspaper as from “good old farmer stock”--lived just outside of Delphi, Indiana. They seemed like an ideal family. The father, Peter Mabbitt, was both wealthy and respectable. The children were all attractive, intelligent, and popular. The belle of the family was 23-year-old Luella, who, naturally, had many suitors. Her favored beau was a man ten years her senior named Amer Green, but--for what may well have been very good reasons--her father disapproved of him. So strong was Mr. Mabbitt’s dislike for Green that he was able to persuade Luella to write her lover a “Dear John” letter.

Unfortunately, Green did not take his dismissal well. On August 6, 1886, William Walker, the swain of Luella’s twin sister Ella, rode to the Mabbitt house and called Ella out for a chat. As the two were talking, Green appeared, demanding that Luella come out as well. When Ella told him her sister was asleep, Green lost his temper, snapping that if he didn’t get to see Luella, he would “tear the house apart.”

Luella--whether reluctantly or not is not recorded--went out to see Green. The two talked quietly for a few minutes, and then they walked off together. After a moment, Walker drove off, and Ella went back to the house, little guessing that this would be the last time she would ever see her sister.

When Luella failed to return that night, her family was naturally alarmed. Equally inevitably, their first thought was to hunt down Amer Green. The local police questioned both Walker and Green, but neither of them claimed to have any idea what had happened to Luella. A massive search was made of the area, without finding any trace of the missing young woman. Peter Mabbitt hired a private detective, and offered a substantial reward for any information about his daughter, but no clues emerged. It was as if Luella had simply evaporated into the air.

When Amer Green quietly slipped out of town, that only hardened local certainty that he knew exactly what had become of Luella. On August 12, a mob of the lynching variety was soon assembled around the Green home. They dragged Amer’s mother out, placed a noose around her neck, and demanded that she tell them where her son had gone. She either couldn’t or wouldn’t say. Eventually, the frustrated crowd let her go and left. As the prime suspect in the disappearance was unable to be found, police did the next best thing. They arrested Mrs. Green. William Walker was tossed into jail as well, apparently only because he had the bad luck to be on the scene the night Luella vanished.

As it turned out, Amer wasn’t the only member of his family with an alleged penchant for murder. His brother William had been accused of killing one Enos Brumbaught, and he too had fled justice. Pinkerton detectives eventually managed to track the pair down in Texas. They were arrested in July 1887 and brought back to Indiana.

In the meantime, the mystery of the whereabouts of Luella Mabbitt had finally been solved...maybe. In February 1887, a body was discovered in the Wabash River. It was so badly decomposed as to be unrecognizable, but Ella Mabbitt and her mother believed that these were Luella’s remains--largely, apparently, on the grounds that the corpse’s teeth resembled Ella’s. Peter Mabbitt, on the other hand, was unconvinced. A physician who examined the body believed the teeth were of someone much older than Luella, and, furthermore, the corpse was that of a man! The uncertainty about these remains only ensured that the Mabbitt Mystery was even more muddled than before.

Meanwhile, Amer Green, from his cell in the Carroll County jail, continued to insist that Luella was alive and well and living in Texas with a man named Samuel Payne. He refused to say any more than this, intimating that all would eventually be made clear.

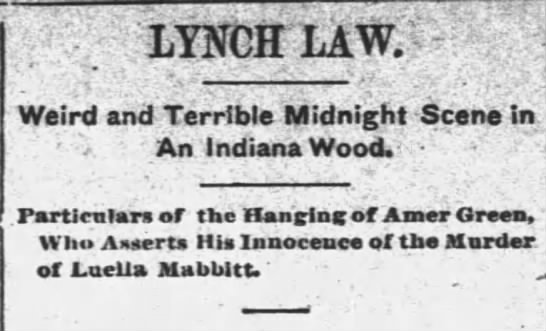

If Green truly did have evidence that Luella was still among the living, he was soon to regret keeping it to himself. Locals were convinced he was a murderer, but lacking a verified body or any other hard evidence that Green--or anybody else--had murdered Luella, it was looking increasingly unlikely that he would ever be convicted. The men of Delphi began to say that if the law could not punish Amer Green, well, they would have to do so themselves.

On the night of October 21, 1887, some two hundred men quietly marched through the streets, surrounding the county jail. They broke their way in and confronted the sheriff, demanding the keys to the prison. When he refused, some of the mob overpowered him, and the others used sledgehammers to break the locks leading to the cells. They went straight to the cell containing Amer Green. At gunpoint, he was seized and tied up. He was led outside and forced into a covered wagon. It drove off, with the bulk of the crowd following.

The wagon drove to the woods of Walnut Grove, about eight miles away. It was soon joined by a large caravan of carriages, wagons, and men on horseback. Green was taken out of the wagon and ordered to confess his guilt.

Green maintained the stolid calm of a man who knows he’s doomed. He quietly maintained that Luella was in Fort Worth. When asked why, if this was the case, she didn’t come home and resolve the mystery, he replied, “She would if I had the time to send for her.” He claimed that Luella had been desperate to leave her home for some time, and on the night she vanished, he had merely assisted in her desire to run away.

Among the crowd was Peter Mabbitt. He stepped forward and begged Green to tell the truth. What had he done with Luella?

“I loved her better than my own life,” Green retorted. “That is the reason I went away with her. I loved her better than you did and all the times she has been away I have cared for her.”

His words were not enough to convince a mob bent on murder. A rope was tied around a branch of a walnut tree and the other end wrapped around Green’s neck as he stood in the wagon seat. The wagon lurched forward, leaving the condemned man dangling in the air.

When it was clear that Green was dead, the crowd soon dispersed, leaving the body hanging in the tree. Before the coroner took charge of it the next day, thousands of people came to gawk at the grotesque sight. Someone took a photograph of the hanging corpse, which was--I kid you not--turned into a postcard. (Copies can be found online, but I strongly urge you not to try to find them.) The men responsible for Green’s lynching were never punished. To this day, Green’s ghost is said to haunt the grove where he died.

|

| "Jackson County Banner," October 27, 1887, via Newspapers.com |

Green’s death was not the end of the mystery. Detectives went to Fort Worth in an effort to track down this elusive “Samuel Payne.” Somewhat to their surprise, they found a Mrs. Orr, who claimed to have lived next door to Payne and a woman who said she was his wife. “Mrs. Payne” was a pretty woman in her early twenties, who told Mrs. Orr that she was originally from Indiana. Unfortunately, the couple had since left town for parts unknown. If this was, as Amer Green insisted with literally his dying breath, Luella Mabbitt, she was never heard from again.

This was not the end of the Mabbitt family tragedies. In 1890, Luella’s 17 year old sister Minnie became pregnant. Upon hearing of the news, the baby’s father, one Charles Spilter, promptly washed his hands of her. Not knowing where else to turn, Minnie sought the help of her brothers, Oris and Mont. They helped her check into an Indianapolis hotel under the name of “Mrs. Minnie Jones,” where she gave birth to a daughter she named “Merle.”

Soon after this, the body of a baby girl was discovered in Eagle Creek. A coroner determined that she had died of strangulation soon after birth. Two women from the hotel where Minnie had stayed identified the baby as Merle. A buggy weight that had been used to weigh down the tiny corpse was determined to have come from the livery stable where Mont Mabbitt worked. It was also learned that on the night Minnie checked out of her hotel, Mont took out one of the stable’s buggies. Minnie, Mont, and Oris were all arrested.

Minnie soon confessed all. She stated that she had believed her brothers would place her baby in an orphanage. She last saw the child when her brothers drove her in the direction of Eagle Creek. Mont took Merle from her and left their carriage. Oris and Minnie drove off for a while, and when they returned, Mont was waiting for them...alone. The three then returned to the city. “No one told me the baby was dead,” said Minnie. “But I knew it was.”

During her trial, the beautiful young Minnie won everyone’s sympathy. It was universally believed that she was but a helpless child, completely under the control of her brothers. She was acquitted of murder, much to the approval of those in the courtroom. Eventually, Oris and Mont--who both argued that they had never intended to murder the baby--were also set free.

In the legal sense, this was the end of the Mabbitt saga. The lingering question of just what, exactly, became of Luella Mabbitt was never resolved. For many years after that fateful night in August 1886, there were periodic “sightings” of the supposedly murdered woman. In February 1916, her sister Ella told a reporter, “For all I know, my sister may have not been murdered and may be living today.”

If such was the case, Amer Green must rank as one of the unluckiest men in Indiana history.

The jury in the baby-killing trial must have been immensely incredulous to believe the men's story about not intending to kill the child. They're the ones who should have suffered the lynch law. Where's an outraged mob when you need one?

ReplyDeleteThat one shocked me,too. I get the impression that the court was inclined to let them off because they were merely "protecting their sister's honor." And if that meant baby-killing, well, okay.

DeleteLet's not forget that one family was attractive, popular, upright, etc. while the other had a less savory reputation. Optics have always had their influence.

ReplyDelete