|

| "Boston Globe," August 19, 1905, via Newspapers.com |

The true-crime writer F. Tennyson Jesse suggested that not only are some people "born murderers," others are "born murderees." It is when these two types of people happen to find each other that you get A Situation.

It is an interesting theory, but one that tends to fall apart once you study murder cases. For example, it is hard to find a more unlikely "murderee" than seventeen-year-old Mattie Hackett of Readfield, Maine.

August 17, 1905, was a typical day for Mattie and her family. After her father, Levi, finished his work on the family farm, he joined his wife and six children for dinner. After the meal, Levi went to the barn to do some final chores, and Mattie began washing the dishes. The rest of the family went to call on some neighbors, leaving the girl alone in the house. Mattie was a pretty girl, but in bad health--in fact, the very next day she was scheduled to be operated on for appendicitis.

|

| "Boston Globe," August 19, 1905 |

As Levi Hackett came out of the barn, he was approached by a stocky, shabbily-dressed young man, obviously a tramp. The man introduced himself as Alfred Johnson of Caribou, Maine. He stated that he had just been released from a jail term for vagrancy, and he asked if he could have a meal and a place to sleep overnight before he returned to his home. Levi replied that his house was full, but the ex-jailbird could sleep in the barn.

The pair walked to the kitchen window, and Levi asked his daughter to get the stranger something to eat. She cheerfully agreed. While the girl began assembling a meal, Levi and the tramp returned to the barn. Just a few minutes later, they heard the sounds of muffled voices coming from the road adjoining the barn. Johnson started to go to see what the commotion was about, but Levi stopped him. It was only some of the children quarreling, he shrugged.

As the two left the barn a short time later, they heard something considerably more ominous: from down the road, they heard a woman scream--in an odd, high-pitched way--"Oh, you dirty nasty thing!"

Alarmed by the cry, Levi rushed into his kitchen. Mattie was not there. As he stood in the doorway, wondering what on earth to do next, he heard even worse sounds: an anguished cry for help, followed by strange gurgling noises.

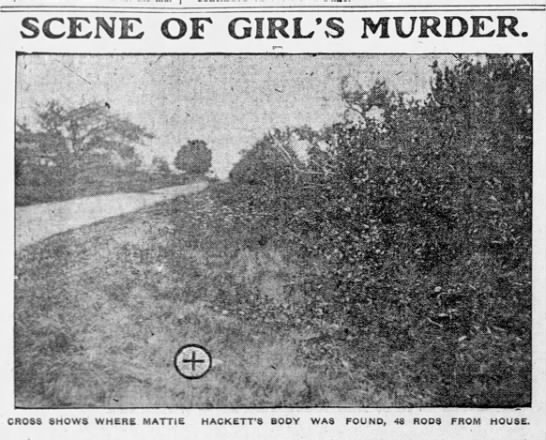

These cries seemed to come from down the road, around a little bend. Hackett dashed in that direction, leaving the confused Johnson standing in the yard. Not far from his home was a ditch, at one end of a culvert. It was here that Levi found his daughter. She was alive, but unconscious. Blood was flowing from a cut on her forehead. Hackett's yells for help soon summoned the rest of his family, along with a half-dozen startled neighbors, and they carried the stricken girl into the house.

At first, everyone assumed that the sickly Mattie had merely fainted, injuring her face as she fell. Her parents loosened her clothing, rubbed her hands and feet, and even threw cold water in her face to revive her. Despite their desperate efforts, her breathing was clearly becoming more and more labored. As Levi picked the girl up to carry her to bed, her head fell forward. It was only then that they saw that a cord had been tied around Mattie's neck, embedded tightly enough in her flesh so that it was nearly invisible. Tragically, by the time the family was able to remove the cord, Mattie was dead. Her parents were forever haunted by the thought that if they had only seen the cord sooner, they could have saved their daughter.

|

| "Boston Globe," August 19, 1905 |

Mattie Hackett had been murdered, and in an unusually strange and inexplicable way. Someone had lured the girl outside, led her a short way down the road, and strangled her. But who? And why?

The initial assumption was that the crime was committed by the "usual suspects" of the era: vagrants like Johnson and his ilk. Readfield organized posses who searched the area for suspicious tramps, but no likely candidates could be found. Johnson himself was held in prison for months as a material witness, but he finally had to be released when it became clear that he had nothing to offer the investigation.

In any case, it soon became increasingly obvious that Mattie almost certainly was killed by someone she knew. She would hardly have willingly left with a stranger. And if she had been forcibly removed from the kitchen, surely her father nearby would have heard the commotion. Also, the kitchen showed no sign that any struggle had taken place there.

Within a few days of Mattie's death, law enforcement developed a new theory, one that they never really relinquished: a woman had been responsible for the crime. One particular woman, in fact: Elsie Raymond, the 21-year-old wife of a local hostler. The scenario put together by investigators was this: Elsie's husband Bert had been paying warmer attentions to the attractive Mattie than was proper for a married man. The heavily-pregnant Mrs. Raymond became increasingly maddened by jealousy. On the fatal evening, Bert rode to the Hackett home and called Mattie out for a short talk. Elsie had followed her husband, and, finding him with her perceived rival, went into a rage so violent that she cried, "Oh, you dirty, nasty thing," grabbed a cord and throttled the girl.

|

| "Boston Globe," August 21, 1905 |

Investigators were not without evidence to support this lurid outline. On the day of Mattie's death, the Raymonds had been overheard quarreling. A woman who boarded with them testified that Elsie had left the house early in the evening, and did not return until after midnight, when she was crying and clearly deeply shaken. Someone else claimed that Elsie had once told her, "If Mattie Hackett ever crosses my path, I will kill her." Yet another witness stated that shortly before Mattie was attacked, she had seen Elsie moving quickly down the road in the direction of the Hackett farm.

In addition, there was what was probably the most intriguing clue in the entire case. Mattie had been living with an aunt in nearby Bartlett, while she worked in a five and ten cent store in that town. However, in recent days she had returned home, due to her poor health. Two of the girls she worked with told investigators that Mattie told them she was afraid of a man in Readfield, and for that reason was reluctant to return home. She went on to say that this man had once courted her, but she decided she didn't care for him, and gave him up. Her former lover married another girl, but Mattie still feared him. She never claimed that this man had threatened her, and she never specified the reason for her unease. Most unfortunately, she also never gave his name. Was this "mystery man" Bert Raymond?

However, there was much in favor of Mrs. Raymond's innocence. For one thing, it seemed unlikely that a woman three weeks away from giving birth could have covered two miles of steep, rocky road in the twenty minutes between the time she was last seen at her home and Mattie's murder. For another, it was soon established that all of Bert's known "attentions" to Mattie consisted of once taking her and her sister Nettie home from work. Most importantly, the footprints found around the site where Mattie was attacked were of size seven shoes. Mrs. Raymond's size was four and a half.

Despite the weakness of the case against Mrs. Raymond, she remained law enforcement's only suspect, and they were determined to pursue charges. However, not one, but two grand juries were assembled to hear the case against Elsie, and both refused to return an indictment. The Raymonds stood the cloud of suspicion over their heads for a year, after which, sick of the gossip which continued to hound them, they moved to a neighboring town.

Time went on, and it looked like the murder of Mattie Hackett would be destined to become a forgotten cold case. Then, in March 1912--almost seven years after the girl's death--County Attorney Joseph Williamson stunned everyone by obtaining an indictment of Elsie Raymond. He had been convinced from the beginning that Mrs. Raymond was a murderer, and he felt he could finally prove it. Her trial was set for the following November.

|

| "Boston Globe," April 7, 1912 |

The state's case against Elsie was one of the most curious in legal history: in essence, they argued that Mrs. Raymond's advanced state of pregnancy had made her crazed enough to turn savage garroter. The prosecution evidence consisted almost solely of various medical experts testifying that women about to become mothers often developed a derangement of the mind, which quickly disappeared after giving birth. (This must have made the husbands of pregnant women throughout Maine very uneasy.) They offered to accept a plea of "not guilty by reason of temporary insanity."

The defense scornfully rejected any such thing. Their client was completely innocent, they declared, and they would accept only an acquittal. They pointed to the exculpatory footprint evidence. They pointed to the fact that witnesses could not swear that a veiled woman they claimed to have seen rushing toward the Hackett farm that August night in 1905 was indeed Elsie Raymond. Additionally, if the Raymonds were at the death scene, how did they leave? The dying Mattie was found only a few minutes after she was strangled, but no one saw either of the Raymonds anywhere in the vicinity.

The defense argued that not only could they prove their client's innocence, they believed they had found the real murderers. They put on the stand a half-dozen witnesses claiming that in 1906, an army deserter named William Hurd had told them he had witnessed a gang of his fellow tramps murder Mattie Hackett. He subsequently committed suicide, without ever revealing the names of the guilty parties.

Alfred Johnson also took the stand, telling a story substantially different from his earlier accounts. He now claimed that when he was in the barn with Levi Hackett, he heard a man's voice say, "Can't you come down tonight," with a woman replying, "No, I can't come down tonight." The voices moved further down the road. Soon afterward, he heard two women talking, followed by the cry of "You dirty, nasty thing," and a choked-off scream.

Alas for the prosecution, before this--to put it most charitably--imaginative testimony could even be completed, the jury announced they had heard quite enough to return an acquittal. Mrs. Raymond was freed.

It was an extremely popular verdict, one which allowed the Raymonds to live the rest of their lives in peace. However, it did absolutely nothing to solve a puzzle which seems fated to forever remain a mystery: Who killed Mattie Hackett?

I have to agree that Mrs Raymond was a very unlikely suspect. A heavily pregnant woman 'rushing' about and strangling a rival? And the theory was that Mr Raymond was present? He never gave any indication that he saw anything untoward, nor, apparently, was he questioned about it. And though it may seem sexist, garrotting isn't a common form by which a woman commits murder, especially a woman weeks away from giving birth. The old chestnut about a tramp being the killer seems more probable than Mrs Raymond's involvement.

ReplyDeleteI suspect that William Hurd was telling the truth. It’s too much of a coincidence that Johnson, who is a stranger to the family and the area, just happens to turn up immediately before a violent crime is committed. He was probably trying to get a place to sleep inside the house so that he could let his accomplices in during the night to ransack the place. Failing that, he could still distract the farmer for a few minutes while they dashed into the house to grab whatever they could. If Levi Hackett had gone with Johnson to investigate the “muffled voices coming from the road” he would probably have walked into an ambush.

ReplyDeleteMattie Hackett knew that her father had offered Johnson a meal so she may have been lured out of the house on some pretext by a member of the gang claiming to be a friend of Johnson who had also been offered help. Alternatively, she may simply have been taken by surprise and overpowered, and only managed to call for help when she was already out on the road. In either case, they killed her to silence her once the alarm was raised. There wasn’t enough evidence to charge Johnson with anything, but his role seems quite obvious and it explains why he changed his story to implicate Elsie Raymond.