|

| Mary Fields, circa 1895 |

There are strong women. There are formidable ladies. There are tough cookies. There are female badasses.

And then there is “Stagecoach” Mary Fields, who was surely in a class all her own. As is the case with so many larger-than-life figures, much of Fields’ life history is murky and a good part of the rest shrouded in the fog of mythology, but there is enough reliable information to guarantee her an honored place in the hallowed pages of Strange Company.

Fields was born into slavery, possibly in Tennessee, sometime around 1832. She first appears in the historical record as a slave in the West Virginia household of a family named Warner. When she was freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, she made one vow: that no one would dominate her again. As she was over six feet tall, weighed around two hundred pounds, and could “pick up a quarter of beef like a potato,” the wise were happy to oblige her.

The newly-freed Fields took to the road. She traveled up the Mississippi River, working on the riverboats and acting as a servant for families who lived along the river. By 1870, she was again working for the Warners, this time as a paid domestic servant. When one of the Warner daughters became a nun, Fields accompanied her to the Ursuline Convent of the Sacred Heart in Toledo, Ohio. Mary became the convent’s groundskeeper.

It made for an odd mix. It is said that when one of the nuns asked if she had had a good journey, Fields replied, “I’m ready for a good cigar and a drink.” Mary’s proud nature, fiery temper and “difficult” personality brought an unaccustomed volatility to the hitherto peaceful convent.

Especially when you messed with her gardens. Mary was a passionate and skilled gardener, and when anyone interfered with her landscaping, prayers were needed. “God help anyone who walked on the lawn after Mary had cut it,” one nun later recollected.

In 1884, the convent’s head, Mother Amadeus, was sent to St. Peter’s Mission in Montana Territory, in order to establish a school for Native American girls. When Mother Amadeus came down with pneumonia a short time later, Fields, along with several nuns, went to St. Peter’s to help keep the mission going. After Mother Amadeus’ recovery, Fields decided that the wild, wild west was much more her style than the staid atmosphere of Toledo. She stayed on at the mission as a general caretaker: raising vegetables, tending chickens, hunting game birds, doing laundry, and repairing buildings. She had free room and board at the mission, but refused to accept a salary. Fields wanted to have her independence, and remaining a non-contracted worker enabled her to come and go as she pleased. In the words of Fields’ biographer Dee Garceau-Hagen, the former slave relished “the pungency of freedom.”

The locals didn’t know what to make of Fields. An Amazon-sized black woman who drank, smoked, swore, was as strong as any male, hauled freight, and readily raised hell with anyone who crossed her was a whole new experience for them. The Native Americans dubbed her “White Crow” as she was someone who “acts like a white woman but has black skin.” A white schoolgirl wrote an essay about Fields noting, more bluntly, “She drinks whiskey, and she swears, and she is a republican, which makes her a low, foul creature.”

One day in 1892, she had a row with John Mosney, one of the mission’s male hired hands. (It is surmised that he objected to taking orders from a black woman. Or maybe he walked on her lawn.) The quarrel culminated with the pair pointing rifles at each other. After that episode, the bishop decided Fields was too, well, vivid a personality for their cloistered society, and he ordered that she be banned from the mission.. He probably felt she was just too much for God. As “overbearing and troublesome” as Fields could be, the nuns at St. Peter’s had become attached to her, and felt that the eviction was horribly unfair. Fields, too, had hoped to stay at the mission for the rest of her days. However, orders from up top were orders from up top, leaving them with no choice but to obey. Fields moved to the nearby town of Cascade, where, with the help of Mother Amadeus, she opened a small restaurant.

As cantankerous as she could be, Fields was also open-handed, generous, and unconcerned about money, which guaranteed her failure as a businesswoman. She readily served meals to everyone who dropped in, blissfully unconcerned about whether or not they could pay for the food. You will not be surprised that the eatery folded in less than a year. She went on to do a series of odd jobs, becoming locally famous for her fondness for whisky and her irascibility. The town’s newspaper claimed--with a distinct air of pride--that Fields had “broken more noses than any other person in Montana.” When one man was crude--not to say suicidal--enough to hurl a racial slur in her direction, Mary sent him to the hospital with a broken head.

In 1896, she applied for a job as a mail carrier. Local postal employees were dubious about hiring a woman in her sixties until, much to their astonishment, they saw that she could hitch a team of horses faster than any man. She was only the second woman, and the first black woman, to work for the Postal Service.

In 19th century Montana, delivering the mail was not a job for the weak and timid. On her route, Fields had to face primitive (or nonexistent) roads, often harsh weather, and the occasional highwayman.

None of this fazed Fields in the least. If her stagecoach broke down, she fixed it. If the winter snows grew too heavy for the horses, she would put on snowshoes, toss the sacks of mail over her mighty shoulders, and deliver them on foot. If anyone tried to rob her, she shot them. According to one story, she once took on a pack of wolves--and won. She never missed a day. Before long, her stellar record earned her the affectionate nickname of “Stagecoach Mary.”

Our intrepid heroine--Cascade’s only black resident--became a near-folkloric figure in the area. Despite the inevitable racial prejudice she often encountered, to many people she was a source of local pride, or in the words of the town newspaper, “a sort of landmark.”

Another thing that set Fields apart is that after leaving St. Peter’s, she no longer sought the company of women, white or black. She ignored the black community institutions being formed in Montana, and there is no evidence she participated in any white churches or civic groups. Instead, her main socializing was with white men in their standard pursuits: sports events, billiard halls, and saloons. Her anomalous role in Cascade’s society only intensified her already colorful reputation, giving her a curious license enjoyed by neither black men or white women.

|

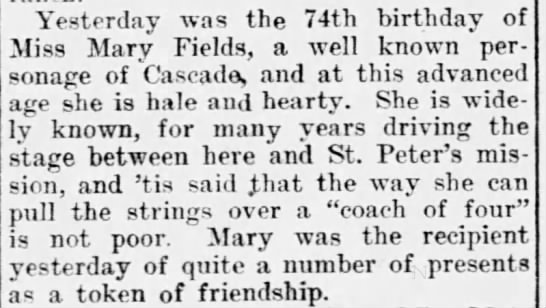

| "Great Falls Tribune," March 17, 1904. Note: as Fields did not know when she was born, every year she would pick a date that suited her fancy as her "birthday." |

Fields retired from her route in 1903, at the age of approximately 71. She occupied herself with babysitting, operating a laundry service, gardening, watching baseball games (she loved the sport,) and, of course, whisky. Mary stayed Mary to the end. According to one report, when a customer failed to pay his laundry bill, she broke his nose. She would give flowers from her garden to the home baseball team and give the umpire hell when he called against them.

|

| Fields with the Cascade baseball team, 1914. Great Falls Tribune, May 22, 1939, via Newspapers.com |

Stagecoach Mary died of heart disease in 1914. Her funeral--held, appropriately enough, at the town theater--was one of the largest the area had ever seen.

Loved this !

ReplyDeleteThank you for sharing her story.

ReplyDeleteQuite a character, all right, and probably only to be at home in frontier districts. But of all the story, I rather like the name 'Mother Amadeus' best...

ReplyDeleteI wish I could have known her.

ReplyDelete