Monday, June 1, 2015

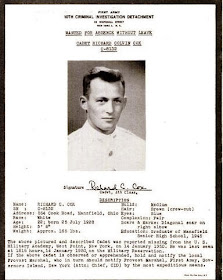

A Disappearance at West Point: The Case of Richard Colvin Cox

It is a curious fact that many of history’s most bizarre mysteries center around people who had appeared to be the most “normal,” or even “ideal” figures imaginable.

An outstanding example is Richard Colvin Cox. The 21-year-old West Point cadet was handsome, highly intelligent, ambitious, well-liked, hard-working and clean-living. After a fine two-year Army career, where he was stationed in Germany, he achieved his life’s great dream when he secured an appointment in the Military Academy. He was very much in love with his fiancée, a pretty girl from his hometown of Mansfield, Ohio, and appeared to have sterling future ahead of him. In short, he seemed to be the last person in the world to have his life engulfed by The Weird.

But that was exactly what happened.

Cox’s Golden-Boy existence began to tarnish on January 7, 1950. The cadet who was Charge of Quarters in Cox’s company received a phone call from a man asking if “Dick Cox” was there. The caller left a message: “Just tell him George called--he'll know who I am. We knew each other in Germany.” (Unfortunately, the cadet who took the call could only be “fairly certain” the man gave his name as “George.”) When Cox was told of this phone call, he claimed to have no idea who the man could be. However, when “George” came to see him later that evening, he recognized him at once. The two men seemed happy to see each other, and they left together. It was presumed they were headed for the Hotel Thayer, the one dining establishment open to cadets other than the mess hall. Instead, they sat in “George’s” car, drinking whisky.

When Cox returned to his room an hour and a half later, he was drunk, which was very much out of character for him. He was so inebriated he immediately fell asleep at his desk. When the 10:30 tattoo sounded, his two roommates were startled to see Cox suddenly spring to his feet and run into the hallway, shouting something peculiar. The two roommates thought it sounded like “Alice!” but it has also been speculated that he was crying “Alles kaput,” German for “All is ended.” We will never know for sure what Cox was saying, or what this unguarded heart-cry could have meant.

Cox quickly pulled himself together somewhat. He returned to the room, and, ignoring his roommates’ questions, fell on his bed and went instantly back to sleep. The next morning, he told his roommates something about his experiences the previous night. He claimed that his visitor, whose name he never mentioned, had been part of his outfit in Germany. Cox described him as “a morbid guy,” who liked to talk about all the killing he had done in the army. Cox added that “this guy” had also impregnated a German girl, and then murdered her. Despite his expressed disgust with his acquaintance, he had another meeting with the stranger that afternoon.

The following week seemed perfectly normal. Cox’s grades remained high, and his behavior impeccable. Then, on January 14, despite the fact that he had expressed hope that “he wouldn’t have to see that fellow again,” Cox was seen talking with “George” near his barracks. Soon afterwards, he told a friend that he would be having dinner with his mysterious acquaintance, although he did not appear to relish the idea. His fellow cadet later said that Cox seemed to think of seeing “George” as an unpleasant duty, but one that, for whatever reason, he could not avoid. A little after six p.m., Cox left his room to see “George.”

That was the last indisputable sighting of Richard Colvin Cox. Although he had signed out, no one reported seeing him leave the barracks. There is no record of him dining at the Thayer that night, or anywhere else for that matter. He simply vanished.

When Cox failed to return the next morning, the police and C.I.D. were called in. The search for the cadet became the biggest manhunt in West Point’s history. And it was all in vain. Although the case has spawned much fanciful theorizing, no one has ever determined what became of this young man whose promising life ended so quickly and bizarrely.

“George” has also remained a phantom. Rigorous investigation never found a clue indicating who he was, or where he went. Although it is generally assumed that he was behind Cox’s disappearance, it is a complete mystery how or why he would spirit off the cadet.

As can be imagined, the usual wild theories floated around. Did the cadet flee in fear for his life as a result of his testimony in a court-martial? Was he somehow involved in the murder he claimed "George" had committed? Was he kidnapped by the Soviets in retaliation for his counter-espionage activities in Germany?

Most speculation about Cox's fate focuses on his earlier military career, where he had been part of an Intelligence Unit. 1950 was the height of the Cold War, and it has been suggested that Cox was involved in some sort of espionage program that led to him being enlisted as a secret agent by the CIA. While this is probably the most plausible (least implausible?) theory, no real evidence for it has been found.

In their book about the case, "Oblivion," Marshall Jacobs and Harry Mailhafer presented a claim from a retired CIA official that Cox was given a new name by the intelligence community, and spent the Cold War smuggling scientists connected to Russia's nuclear program across the Iron Curtain. Allegedly, Cox died of cancer some time in the 1990s, his true identity still a secret. These authors believed that Cox was likely gay. (A theory however, based mainly on thin rumor.) They argue that this secret--which would have jeopardized his career--inspired the cadet to stage his own disappearance. (For what it's worth, Cox's family rejects this entire scenario, insisting that he would have found a way to contact his mother, to whom he had been very close. Mrs. Cox died in 1986, still tormented by the puzzle of her son's disappearance.) It is impossible to say if Jacobs' and Mailhafer's source--who offered no proof whatsoever for all this--was credible. Their theory also fails to satisfactorily explain why it was necessary for Cox to "disappear" and take on a new persona to his very grave.

Jacobs and Mailhafer also mentioned a curious link to the case. They learned of a suspect in an 1985 murder named Robert W. Frisbee. Many years earlier, Frisbee, under the name of Robert Dion, had been stationed at Fort Knox at the same time as Cox. It was probable that the two had known each other. Frisbee/Dion--who had once been involved in making phony IDs--was said to resemble descriptions of "George." This was all intriguing, but as no one was ever able to conclusively tie Frisbee to "George," and Cox's disappearance, it all proved to be just another brick wall.

There are at least two reports of someone allegedly seeing Cox after he disappeared. In 1954, Ernest Shotwell, who had known Cox in the army, told the FBI that two years earlier, he had run into Cox at a bus station in Washington D.C. The two men spoke briefly, with Cox mentioning that he was on his way to Germany. Shotwell said his old friend was clearly displeased to see him. Cox was agitated and curt, and after a few minutes, abruptly broke off the conversation and stalked off. Shotwell said he had not spoken of this encounter before because he had not known at the time that Cox was a missing person case.

Another reported encounter with the vanished cadet supposedly took place in a Florida bar in 1960. An undercover FBI contact made the acquaintance of a "R.C. Mansfield," who eventually admitted that his real name was "Richard Cox." When this FBI agent later learned of the Cox mystery, he tried to set up another meeting with "Mansfield," but he never heard from the man again. While these reports are considered plausible, they still don't answer the question of why Cox vanished.

Or, to take the simplest theory, did the sinister "George"--for who knows what personal reasons--murder the young cadet and hide the body somewhere in the woods around West Point or deep in the Hudson?

Richard Cox will likely always remain one of America’s classic enigmatic disappearing acts.

Another case with too many clues but none pointing in the same direction. Jacobs and Mailhafer seem to be the type of authors who like to present theories as solutions.

ReplyDeleteFirst of all to Undine, great blog! I've bookmarked it, I love strange history.

DeleteSecondly, I think if I've spent eight years obsessively researching something only to come up equally empty-handed as other before me, I'd also start presenting theories as solutions. For my own sanity. LOL

The quote under the picture was not by Poe.

ReplyDeleteIt's from his "Marginalia," "Southern Literary Messenger," June 1849.

Delete