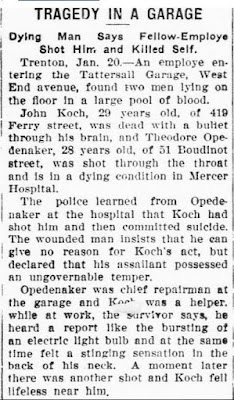

|

| Travers Twiss |

One of the few advantages to our modern world is that blackmailing has largely become obsolete. Nowadays, when someone harbors a shocking and sordid secret about their personal life, they don't quiver in fear at the thought that it may one day become public; they write a book, get millions of followers on Twitter, and make a fortune out of it.

In the Victorian era, things were very different. People were just as flawed as they are now, and everybody knew it. However, if you wished to move in any sort of polite society, you had to make a great show of gentility, no matter what you got up to in private. Yes, it may have been hypocritical, but the rigid social code did have the advantage of fostering polite behavior and public dignity.

Its disadvantage, of course, was that it was also a blackmailer's paradise. When you have a world where a well-bred man or woman's life almost literally depended on their "good reputation," they were willing to pay almost any price to keep it. One case that forced the Victorians to confront this uncomfortable truth was the Twiss case of 1872.

Sir Travers Twiss was professor of International Law at King's College, London. He was one of the most respected lawyers of his time: wealthy, accomplished, and appropriately colorless. He had one spot of romance in his stodgy life: In 1859, the fifty-year-old Sir Travers met beautiful 22-year-old Marie Van Lynseele, the daughter of a Polish General. Three years later, he married her. After the wedding, the charming new Lady Twiss was presented to the Queen, and the couple happily settled down to a quiet, comfortable life.

The pair was the model of dull respectability until one day when Sir Travers and his lady were walking in Kew Gardens. They were approached by a man whom Lady Twiss introduced as a solicitor named Alexander Chaffers. Chaffers politely congratulated her on her marriage, and nonchalantly went on his way.

Soon after this encounter, Chaffers sent Lady Twiss a bill for £46. His note said enigmatically that it was for "services rendered." She made no answer. The solicitor then sent her a second bill, upping the price for his "services" to £150. Lady Twiss, realizing that the man was not about to take "no" for an answer, showed the bill to her husband, offering the explanation that it was for legal work he had done for one of her maids. Sir Travers paid Chaffers £50, and got back a receipt.

The solicitor was not satisfied with this. He continued hounding Lady Twiss for money, and when she refused to take any more notice of him, he made a truly viperish move: He wrote to the Lord Chamberlain--the court official responsible for the Queen's guest list--with the information that the "daughter of a Polish general" was in reality a Belgian prostitute who had conned her way into an advantageous marriage.

The Lord Chamberlain figured that this letter was either a sick hoax or the key to a very distasteful Pandora's Box. Either way, he felt the best thing to do was just ignore it. However, he did tell Lord and Lady Twiss about this singular communication. They both assured him that Chaffers' letter was simply the ravings of a lunatic.

Word reached Chaffers of these slurs against his mental condition. He reacted in a way that fully confirmed their accuracy: He sued Sir Travers for slander, and marched off to the Chief Magistrate at Bow Street to make a sworn statement detailing all he knew about Lady Twiss.

And, oh, boy, that was plenty. Chaffers' deposition stated that she was, in reality, Pharsilde Vanlynseele. Under the name of "Marie Gelas," she had worked in several London brothels, where he had been a regular customer of hers. Chaffers added that she had also been Sir Travers' mistress before their marriage.

Once this story came out, Sir Travers felt he had no choice but to have Chaffers arrested for libel, thus ensuring that the whole sordid saga would get a thorough airing in the public court. In her testimony, Lady Twiss stuck to her guns, vowing that she was the genteel Marie Van Lynseele. She stated that both her parents had died when she was young, leaving her to be raised as the adopted daughter of a Felix Jastrenski. She admitted that she had once known someone called "Marie Gelas"--the woman had been her governess--but that, she said flatly, was the closest Chaffers' monstrous story came to any truth.

Chaffers' defense was that he had spoken nothing but the complete truth. He was equally insistent that this "governess" had never existed. The "lady" was Marie Gelas, former prostitute who had, in his words, "struck it rich." Knowing what he knew about her, he saw nothing wrong with trying to profit from his information.

Chaffers freely admitted to being a blackmailer. The trouble was, in 1872 that wasn't illegal. The only way the law could make him pay was if he was guilty of libel.

But was he?

|

| "Illustrated Police News," 1872 |

Lady Twiss made a brave show of trying to prove she was who she claimed to be. Various witnesses were brought in to back her up--including a former maid who swore that Chaffers had tried to bribe her into lying about her mistress. M. Jastrenski himself appeared in court to assert that she had been his virtuous foster-daughter. Things were going well for the Twiss camp. The judge made no secret of his disgust for the defendant, and the public and press were equally full of chivalrous zeal for her cause.

And then came a Twiss twist that no one seems to have expected. Eight days into the trial, the lady suddenly caved. She fled London, leaving her lawyer to explain to the court that she wished to drop the case. The judge had no choice but to let Chaffers go. He did, however, tell the defendant that he would forever be "an object of contempt to all honest and well-thinking men." I doubt Chaffers cared. Men of his caliber tend to wear such words as a good-conduct medal.

English high society had seen the last of Lord and Lady Twiss. She vanished somewhere on the Continent, and permanently disappeared from history. Her subsequent career is unknown. The palace retroactively struck her name from the Queen's previous guest lists. As for Sir Travers, he resigned all his official posts, and retired into what remained of his shattered private life until his death in 1897. He apparently never set eyes on his wife again.

So, what was the truth about Lady Twiss? It has been suggested that perhaps she was indeed innocent of any deception, but realizing that she and her husband were socially ruined, no matter what the truth may have been, she suffered a breakdown of some sort and blindly fled. However, her behavior does seem to make it virtually certain that Alexander Chaffers may have been a rotten skunk, but he was not a liar. The assumption is that she had bribed all her witnesses to back up her claim, until she finally lost her nerve and did a runner.

Whoever or whatever Lady Twiss may have been, her sad experience led to a major change in the law. In 1873, a statute was passed making it illegal to "demand money with menaces." Although the law did little to stem the practice of blackmail, the victims now had at least an outside chance of seeing their persecutors face criminal charges.

As for the villain of the piece, Chaffers' success in evading justice in the Twiss case seems to have given him a taste for bizarre litigation. He went on to file a number of wholly frivolous, but irritating, suits against various members of high society, until he made legal history for a second time. His lawsuit mania directly led to the Vexatious Actions Act of 1896. That legislation empowered law officers to apply to the High Court to have a person declared "a habitually vexatious litigant." If a judge agreed, an order could be issued banning the litigant from initiating any legal proceedings without obtaining permission from the Court. It is some small satisfaction to note that Chaffers' crimes did not ultimately pay. He died in a workhouse.

However, I doubt this was much consolation to Sir Travers and his wife.