Friday, January 29, 2016

Weekend Link Dump

This week's Link Dump is pleased to be sponsored by the Knittin' Kittens!

Who the hell was the Death at Indian's Head?

What the hell is the Dare Stone?

What the hell is the Waffle Rock?

Who the hell killed Elizabeth Short?

Watch out for the monster of Lake Elsinore!

Watch out for Queen Victoria's handwriting!

Watch out for those 85-year-old jewel thieves!

Watch out for those 18th century quacks!

Watch out for the Nine of Diamonds!

South Carolina is really booming!

Schrödinger, Church cat.

Date night in 1953 San Francisco.

John Dee, his mom, and a dwarf.

In a previous Link Dump, we were introduced to a goat snuggler. Now meet the professional panda hugger.

The much-traveled Jeanne Baret.

A visit to a debtor's prison.

The plot to kill George III.

The life of a Texas revolutionary.

Elizabeth Canning and other female "liars and monsters."

This may be the ultimate "don't try this at home" story. Not that I'm betting you'd want to.

The Haunting of Bunny Hall: an eerie--and frustratingly unresolved--17th century witchcraft case.

In which a bogle is a complete failure as an alibi.

The Earl of Bridgewater, who had good taste in dinner guests.

I'm hoping this hotel has changed the sheets during its lifetime.

Isobel Gunn, who had more success as a Canadian man than as a Scottish woman.

The plastic surgeon who got sued for creating a vampire.

The Titanic's sea monster.

A "mail-order bride" comes to a very bad end.

John Collier, whose art aimed to soar to higher things.

George IV's giraffe.

"Dragging his bowels after him." Just to give you fair warning on what you'll be getting with this one.

Why doppelgangers never double your fun.

How to go riding in 18th century style.

The history of the lorgnette.

Mr. Curtiss and his acoustic chair.

Addressing authority in Early Modern Europe.

A ghost in the morgue.

The mystery of the Beaumont children.

Germany's Castle Frankenstein.

The slaves of the White House.

The Berry sisters, 18th century celebrities.

A ghost solves her own murder.

Another ghost fails to solve her own murder.

London's Sailortown.

Thomas Oliver, who was in the habit of marrying witches.

The women of the early days of ballooning.

Photographs of 19th century Glasgow.

A duel between doctors.

The curious case of the Dromedary Scrimshaw.

The rice recipe that was responsible for a nervous breakdown.

Letters to a 19th century witch.

That time a nuke crashed into Canada.

In related news, I'd love to see a Swear Like a Viking Day.

Medieval cosmetics.

One of my favorite moments in Weird New York: The Great Rocking Chair Riots.

An Italian ghost story.

A disappearance at a Japanese shrine.

The executed criminal who wrote his own elegy.

Drain a Paris canal, and you never know what you'll find.

Ghosts of the Japanese tsunami are looking for a ride.

The history of Victorian dog shows. (H/t The Pet Museum.)

Pity Houdini's ghost. No one's listening to him.

Modern British witchcraft.

What Google Earth doesn't want you to see.

The busy career of Julia Ward Howe.

An 18th century public apology.

Souls trapped in photographs.

A 10,000 year old massacre.

And with that, we come to the end of this week's Link Dump. See you on Monday, when I'll bring on another case of corpsenapping. As for our Song of the Week, I recently saw "The Martian," (a terrific film, even though I had a few quibbles about the ending,) so naturally, this has been running through my brain ever since.

Wednesday, January 27, 2016

Newspaper Clipping of the Day

This memorable example of "gallows humor" appeared in the "Sacramento Union," March 9, 1922:

NEW YORK, March 9.—The grim humor of a wireless operator, who laughed at death and flashed striking bits of wit into the ether as his ship, the Norwegian steamer Grontoft, wallowed and slowly sank during a mid-Atlantic hurricane last Thursday, was recorded on the radio log of the Danish steam Estonia, arriving here today. Each detail of the ship’s plight, each call for aid, was supplemented by the jesting comment of the radio man, whose identity is still unknown. He talked as If he were going on a lark in port, instead of to the bottom of the sea. His last message, a disjointed one, was a series of witticisms —with death as the butt of the joke. The Estonia, herself hard hit in the 110-mile gale, made a valiant, but unsuccessful, effort to reach the Grontoft, which first sent out calls for aid at 10 o’clock last Thursday morning, reporting her position as about 700 miles east of Cape Race. The Estonia at that time was 48 miles west of the disabled Norwegian and steaming in an opposite direction. Captain Hans Jorgenson ordered his ship about and she steamed slowly toward the Grontoft, Meanwhile radio Operator Hansen engaged the operator of the Grontoft in conversation. The latter sent out first the following—stereotyped irony of the seas: “God pity the poor sailors on a night like this.” Then followed a series of “Ha, ha,” “and say,” he continued, “the old man thinks this calm will be over by nightfall. We sure need some breeze.”

An hour later an urgent call for aid was sent out by the Grontoft and her operator jested again. “Well, the steward is making sandwiches for the lifeboats. Looks like we are going on a picnic.’’ Again a half hour later he sent: “The old wagon has a list like a rundown heel. This is no weather for a fellow to be out in without an umbrella.” “Hold on,” returned the Estonia’s wireless, “we’ll be alongside soon.” The Grontoft did not reply until 40 minutes later. Then: "We are sinking stern first. The boats are smashed. Can’t hold out any longer. The skipper dictated that—he ought to know —where did I put my hat—sorry we can't wait for you, pressing business elsewhere." The Estonia’s operator quoted in reply these lines: “What dam of lances brought thee forth to jest at dawn with Death?" But there was no answer. Six hours after picking up the first call from the Grontoft, the Estonia reached her reported position, and though she cruised about for four hours, failed to find even a trace of wreckage. The Grontoft, from Galveston, New Orleans and Norfolk, was en route for Esbjerg. She had a crew of thirty.

It was later reported that the operator who "jested at dawn with Death" was a 26-year-old Norwegian named John Frantzen. His fiancee had been waiting in Esbjerg to meet him.

There was another eerie story associated with the ill-fated radio operator. Before its last voyage, the Grontoft crew went to the Norwegian consul in New Orleans to complain about the inedible food in their ship's mess. As the men were leaving, Frantzen drew a picture of the Grontoft on the walls of the corridor outside the consul's office. Underneath the sketch he wrote, "We wish you a happy voyage to Hell--if not this summer, then next year."

Rest in peace, John Frantzen. You had style.

Monday, January 25, 2016

The Case of the Kidnapped Corpse [Part One]

|

| Alexander Stewart |

Everyone, of course, has heard of kidnapping people for ransom. Most are also aware of the historical practice of stealing dead bodies from their graves for the purpose of selling them to medical colleges as anatomical subjects. Heinous as such actions are, they are relatively "normal" crimes.

It's when the acts are combined, and you see dead bodies being kidnapped, that things really get weird.

America's most notorious case of corpsenapping was probably that of millionaire department store mogul Alexander Turney Stewart. The tycoon died on April 10, 1876 at his New York mansion. Stewart was given an appropriately lavish funeral, after which he was buried in a marble vault at the church of St. Mark's-in-the-Bouwerie. There his remains were left--or so everyone fondly imagined--to rest in peace until his more permanent crypt in Long Island could be completed.

All was quiet until the morning of November 7, 1878, when Frank Parker, St. Mark's assistant sexton, arrived at the church, only to be greeted by a nightmarish sight: a large hole had been dug over the Stewart vault. Parker saw that ghouls had battered through the merchant prince's coffin and made off with his bones. Also missing were the coffin's silver name-plate, its knobs and handles, and a patch of the coffin's velvet lining.

Everyone was naturally stunned. Who could have committed such a gruesome act, and why? Stewart's executor, Henry Hilton, posted a $25,000 reward for the body's recovery, but received no replies. The crime remained an unsolved mystery until January 1879, when Stewart's widow, Cornelia, received a letter posted from Canada. The writer, who used the presumed pen name "Henry G. Romaine," offered her the return of her husband's corpse--in exchange for $200,000.

I have no idea how much Cornelia Stewart valued her husband when he was alive, but it's clear that she didn't think he was worth very much dead. She entered into no-nonsense negotiations with her nameless foe, (conducted largely through the personals section of the "New York Herald,") where she not only demanded proof that the bones he had were indeed those of her husband, she managed to knock down the asking price to $20,000. The grave-robber sent her the silver knobs and name-plate that had been removed from the coffin, and the deal was struck.

An envoy (variously described as Cornelia's lawyer or one of her grand-nephews) was given the dubious honor of carrying out the exchange. Late one night, he drove a buggy out to a remote spot in rural Westchester County. He was met by a masked horseman, who, after offering the piece of velvet cut from Stewart's coffin as proof of his legitimacy, handed over a bag of bones. After receiving the money in return, the miscreant vanished.

The grave-robbers were never identified. Also left unanswered was whether the bones returned to the Stewart family really belonged to the late tycoon. It has been suggested that the thieves, not wishing to keep such unpleasant relics about the house, ditched them soon after the exhumation, and, when an opportunity of making money arose, palmed off on the family the bones of some anonymous stranger. The Stewarts could have settled the matter by subjecting the bones to forensic examination, but they flatly refused to do so. Perhaps they felt that having their patriarch's corpse stolen for ransom was indignity enough. Learning that they had spent 20 grand for a ringer would have been just too much.

In any case, the Stewarts placed the remains in a fine casket and buried them in the newly-built family vault at Episcopal Cathedral of the Incarnation in Garden City. According to legend, an elaborate alarm system was set up around the coffin which would set all the cathedral bells ringing if anyone made another effort to monetize Alexander's corpse.

It has never been needed. The body has been undisturbed ever since.

Whoever it is.

[Tune in next week for another tale of purloining corpses for fun and profit!]

Friday, January 22, 2016

Weekend Link Dump

This week's Link Dump is sponsored by the Fraternal Order of Mews.

What the hell was the Cape Girardeau incident?

What the hell happened to Raoul Wallenberg?

Where the hell are these kings and queens?

Who the hell is this man?

What the hell is KIC 8462852?

Watch out for those Roman toilets!

Watch out for those cursed churches!

Watch out for those sheep-sized ghost rabbits!

Watch out for Two-Toed Tom the Demon Gator!

Watch out for Churn-Milk Peg!

Watch out for those 21st century Serbian vampires!

Watch out for those New Orleans prison ghosts!

New Jersey is really booming!

Kansas is really booming!

Bristol is really humming!

The Regency era was really itching!

The 14th century: Come for the famine, stay for the Black Plague!

Victorian cat funerals.

Why Oscar Wilde's mother was a celebrity in her own right.

Irish shape-shifting Wizard Earls can always expect a warm welcome at my blog.

The evolution of a London street, 1840-2015.

Plagues of Egypt, meet the Great Squirrel Invasion.

The mystery of the Fisher King.

A murder victim's busy afterlife.

A future First Lady has quite the road trip.

Fairy tales are even older than we thought.

The duel between the Madame and the Marquise.

Planet 9 From Outer Space.

A 1917 map of Fairyland.

A Georgian gypsy romance.

No practical joke involving frozen pig tails can possibly end well.

Did a ghost create a miscarriage of justice?

Chronicling advertisements from 250 years ago.

The birth of preserved food for sailors and soldiers.

The birth of the bluestockings.

Educating the poor in 18th and 19th century Norfolk.

The mystery of Kipling's son.

Jolly Jumbo, famed English heavyweight.

The kilt in Georgian England.

The spook lights of New Zealand.

The hermit of Buckingham Mountain.

Georgian costume jewelry.

An 1802 infanticide case.

Worst fancy-dress costume ever?

Fun with coffins!

A guide to Victorian hairstyling.

Sir John Falstaff, highwayman.

The British suffer a "shameful disaster," 1809.

Ghosts, fairies, and Arthur Conan Doyle.

Two landmarks in Arctic exploration.

Yet another not-so-perfect marriage.

Alleged messages from the Titanic.

Is privacy dead?

The Feast of Fools.

In case you are still wondering how to take off your clothes, help is just a click away.

The Irish cat and the Spanish Duke.

Christina Plum learns that karma is a bitch.

A reminder why we are grateful for anesthesia.

"Mortuary Professions for Ladies."

The custom of writing on glass.

How the tomb of Napoleon's son wound up in Canada.

The "frigidity" of Frances Howard. (My take on this superbly weird case is here.)

The hazards of Georgian vanity.

The East India Company in West Africa.

The memoir of a 19th century convict.

Insanity and a horrific 19th century family murder.

Istanbul has a cat-friendly mosque.

Supergirl is alive and living in Yorkshire.

Photographs of life in the Soviet Union, 1967.

The Dinosaur Princess of India.

The tower that memorializes an antelope.

The last of the Hobbits.

An Englishman's view of France, 1822.

A night on the town in 1937 San Francisco.

Beckett Cats! (Perhaps I shouldn't be reminding anyone of this, but a few years ago I did a similar series of Poe Cats.)

A few stories about pigs.

Is this the earliest painting of a volcanic eruption?

Rewriting the history of the early Pharaohs.

Speaking of which, were there ancient Egyptians in Ireland?

Demon skulls? Nazi briefcases? Aliens? Why, it must be time for This Week in Russian Weird!

And that closes this week's Link Dump. See you on Monday, when we'll be kicking off a two part series on kidnapped corpses. In the meantime, here's...SLIM WHITMAN! I love Slim Whitman! I love yodeling!

Because that's just how my bad self rolls.

Wednesday, January 20, 2016

Book Clipping of the Day

Most of my favorite ghost stories deal with wronged spirits getting a bit of their own back. A perfect example is this short-and-anything-but-sweet story told by that famed 17th century gossip John Aubrey in his "Miscellanies Upon Various Subjects."

Sir John Burroughes being sent envoy to the Emperor by King Charles I. did take his eldest son Caisho Burroughes along with him, and taking his journey through Italy, left his son at Florence, to learn the language; where he having an intrigue with a beautiful courtesan (mistress of the Grand Duke), their familiarity became so public, that it came to the Duke's ear, who took a resolution to have him murdered; but Caisho having had timely notice of the Duke's design, by some of the English there, immediately left the city without acquainting his mistress with it, and came to England; whereupon the Duke being disappointed of his revenge, fell upon his mistress in most reproachful language; she on the other side, resenting the sudden departure of her gallant, of whom she was most passionately enamoured, killed herself.

At the same moment that she expired, she did appear to Caisho, at his lodgings in London; Colonel Remes [a Parliament man, and did belong to the wardrobe, tempore Caroli II] was then in bed with him, who saw her as well as he; giving him an account of her resentments of his ingratitude to her, in leaving her so suddenly, and exposing her to the fury of the Duke, not omitting her own tragical exit, adding withal, that he should be slain in a duel, which accordingly happened; and thus she appeared to him frequently, even when his younger brother (who afterwards was Sir John) was in bed with him. As often as she did appear, he would cry out with great shrieking, and trembling of his body, as anguish of mind, saying, O God! here she comes, she comes, and at this rate she appeared till he was killed; she appeared to him the morning before he was killed. Some of my acquaintance have told me, that he was one of the most beautiful men in England, and very valiant, but proud and blood-thirsty.

This story was so common, that King Charles I sent for Caisho Burroughes's father, whom he examined as to the truth of the matter; who did (together with Colonel Bemes) aver the matter of fact to be true, so that the King thought it worth his while to send to Florence, to enquire at what time this unhappy lady killed herself; it was found to be the same minute that she first appeared to Caisho, being in bed with Colonel Remes. This relation I had from my worthy friend Mr. Monson, who had it from Sir John's own mouth, brother of Caisho; he had also the same account from his own father, who was intimately acquainted with old Sir John Burroughes and both his sons, and says, as often as Caisho related this, he wept bitterly.

Monday, January 18, 2016

The Tenants Harbor Mystery

In the late 19th century, one of the more insular and remote American villages was Tenants Harbor, Maine. This town on a sparsely-populated Atlantic peninsula consisted of some fifty or sixty families where the men mostly made a living as fishermen or sailors. The townsfolk were all related by blood or marriage, or both. Particularly during the long winters, the isolation of Tenants was nearly complete. Depending upon the circumstances, such a setting could evoke either Norman Rockwell-style coziness or claustrophobic Lovecraftian horror.

If you are at all familiar with this blog, you can guess which scenario we will be discussing.

One of the loneliest spots in this lonely village was the house of Captain Luther Meservey and his wife Sarah. They lived at the far end of town, surrounded largely by open spaces. There were only two other homes in the area, and they were in no close proximity. Especially at night, it would not have been a desirable residence for anyone with sensitive nerves and an active imagination.

Sarah Meservey seems to have had neither of those qualities. The thirty-seven year-old was, from what little we know of her, a practical, capable sort well able to fall back on her own resources. She took her mariner husband's frequent long absences with equanimity. When Luther went out to sea in October of 1877, leaving his wife to face a winter alone, (the couple was childless,) there is no reason to think either faced the prospect with any particular trepidation.

Sarah's quiet life went on as usual until December 22. On that day, a neighbor woman came by her home for a short visit. That evening, Sarah walked to the village post office to collect her mail. A young girl named Clara Wall accompanied her for part of this errand.

This seemingly inconsequential act earned little Clara her own footnote role in Tenants Harbor history. Because, as it turned out, she was the last person known for sure to see Sarah Meservey alive.

After picking up her letters, Mrs. Meservey simply vanished from sight. For days, then weeks, no one in Tenants saw any sign of her. What is even stranger is the fact that no one in the village seemed to find this at all odd. There is no record of anyone expressing the slightest concern, or even curiosity, about her whereabouts. This tiny, cocooned village had one of its members--a woman well-known to all, and who made regular public appearances--suddenly drop out of sight without anyone so much as raising an eyebrow. For every student of this murder, that indifference is one of the most baffling aspects of what would prove to be an unusually weird case.

It was not until January 29 that questions began to be raised about Sarah Meservey's long absence. Albion Meservey, a cousin of Sarah's husband, went to visit the local burgomaster, Whitney Long. Albion confided to him that no one had heard anything from Mrs. Meservey for quite some time, and, well, perhaps some kind of investigation should be made.

The two men, accompanied by another Tenants resident named Frederick Hart, went to Sarah's house. The shades were drawn, and the place was ominously cold and silent. All the doors were locked, but they found a back window that could be pried open. We do not know what the men might have expected to find when they climbed into the house, but the result of their search probably exceeded even their worst fears. Nothing unusual was found until they entered a spare bedroom. That room was covered in bloodstains. The furniture was disordered. And lying on the floor, wrapped in a blanket, was the dead body of Sarah Meservey.

Her death had been a particularly violent one. Her body was covered in bruises and wounds, suggesting a desperate struggle. Her arms had been pulled behind her head and tied together with a fishing line. Then she was strangled with her own scarf. She was fully dressed and still wore her walking boots, indicating that she was assaulted immediately after her return from the post office three days before Christmas. Blood was also found around the kitchen door and in the sink, indicating that the killer had washed his/her hands there.

Found near Mrs. Meservey's body was a semi-literate note. It read, "i cam as A Womn She was out and i [waited] till she Come back, not for Mony but i kiled her." Nearby were some used matches. They were of a type not used by the Meserveys. Investigators also found a crumpled, bloody paper collar, presumably torn off the killer during the struggle. Even though nothing appeared to be missing from the house, the working hypothesis was that Sarah had interrupted a burglar, who then overpowered and killed her. The note was presumably left as a clumsy red herring.

Nearly three weeks after Sarah's body was discovered, her husband came ashore from his voyage and returned to Tenants Harbor, completely ignorant of the tragedy that had taken place during his absence. He and his wife had been a devoted couple, and when the captain learned the gruesome news, he was devastated. He had no idea who might have done such a brutal deed.

On February 19, one of the Meservey's neighbors, Mrs. Levi Hart, received a very strange letter, as poorly written as the note left by Sarah's body. It was postmarked in Philadelphia. The letter read: "i thought i would drop you A line to tell your husband to be careful how he conducted things about Tenants Harbor cause if he dont he and a good many others of the men will get A ounce ball put threw them for tell them that it is no use trying to catch this chap for he will not be caught--so be careful who you take up in st George you shall hear from me again in three months." It was signed, "D.M." Enquiries failed to reveal who might have sent the note.

Local gossip, evidently based on private reasons unknown to us, quickly fixated on one man as the likely killer of Sarah Meservey. On March 8, he was arrested. The accused was another sea captain, Nathan F. Hart, who was Sarah's nearest neighbor. Hart was described as a "pretty hard character," but other than that vague description, it is hard to say why so many were so willing to believe he was a murderer. A self-described "handwriting expert," a penmanship teacher named Alvin R. Dunton, believed items Hart had written in a log book matched the handwriting of the anonymous messages. Hart was known to use the same type of matches found near Sarah's body. Flimsy though this evidence sounds, it was enough for a Grand Jury to order that Hart stand trial for murder.

Whoever the writer of those mysterious messages may have been, he kept up his sinister correspondence after Hart was put in prison. On May 17, another Tenants resident named Mahala Sweetland was the recipient of yet another letter, this one sent from Providence, R.I. It was the longest and creepiest of them all. As a classic exercise in psychopathology, it is worth repeating in full:

Was this letter genuinely written by Sarah Meservey's killer? Or was it written by an ally of Nathan Hart, in an effort to give him an alibi? Whichever may have been the truth, it is certainly one of the most chilling messages associated with a murder case.

Nathan Hart stood trial in October 1878. A reporter in the courtroom was not impressed with the defendant, describing him as "wearing a smirk that gives [his lips] a crafty, treacherous cast that is not prepossessing." Hart calmly, stubbornly continued to insist on his innocence. His demeanor was "calm and cheerful all the time."

The prosecution's case could be summarized thusly: Mrs. Meservey's killer was skilled at tying maritime knots, and Hart was a sailor. His proximity to Sarah's house gave him the opportunity to know when she was absent. He attempted to rob her, and when she surprised him by her unexpectedly early arrival, Hart felt he had no choice but to kill her. He had no alibi for the night of the murder. He showed evidence of knowing certain details about the murder before they were publicly revealed. Before the body was found, Hart told friends he had dreamed that Sarah Meservey was strangled to death--surely a guilty conscience manifesting itself. A brother of the dead woman recalled that on the day Sarah's body was discovered, Nathan Hart told him that he, Nathan, had known "she was in there dead, all the time." The State presented several handwriting experts who asserted the anonymous letters were in the defendant's hand. Hart, they argued, wrote these letters and arranged to have them posted in various cities in an attempt to draw suspicion away from himself. A Warren Hart testified that a few months before the murder, he was "joking about women" with the defendant and his wife. Mrs. Hart jocularly mentioned an occasion when Sarah Meservey had slapped Nathan's face and pulled out his shirt bosom--presumably when he became a bit too frisky with her.

In response, the defense asserted that the handwriting "experts" were simply all wet. Their client did not write the letters. The various statements attributed to him could hardly be called proof of guilt. Hart's wife and stepdaughter testified that Nathan had been at home all day December 22. A Mr. Whitehouse stated that he saw the defendant at his house around 8:30 of the fatal night.

Alvin Dunton, who had testified for the State at the Grand Jury, now did an about-face by appearing as a defense witness. After studying all the relevant documents, he now believed that Albion Meservey had written the letters. Dunton's appearance on the stand was the unquestioned dramatic high point of the trial. A local newspaper described with unmistakable delight how "Witness here swooped down from the stand on the jury, and inundated them with a stream of eloquence concerning his theories. The sum of all was that Albion K. Meservey wrote the brown-paper note, the Philadelphia letter, and the first five pages in the Log Book No. 1. Witness bobbed from the Judge to the jury like a sewing-machine shuttle, his tongue meanwhile going with a speed that would have left even Miss Pulsifer's [a local court stenographer] facile pen behind, we fancy, had an attempt been made to report him. While Mr. Dunton was thus disporting himself, the audience relapsed into social enjoyment, and the courtroom was like an evening party...Finally, Mr. Montgomery told counsel for State to cross-examine. But witness said he hadn't got through with his testimony..."

It was quickly becoming clear that Alvin Dunton was what every truly great murder case needs: a colorful crank.

Nathan Hart himself then took the stand. He reiterated that he had been at home all the evening Sarah Meservey was murdered. He stated that his dream about Mrs. Meservey had taken place after her body was discovered. He denied that he had urged that her house be searched. He did not write the anonymous letters, and he did not know who had. He had nothing whatsoever to do with Mrs. Meservey's death.

On paper, at least, the evidence both for and against the defendant's guilt appears irritatingly skimpy. However, this did not prevent the jury from returning a verdict of "Guilty of murder in the first degree." The judge sentenced him to life imprisonment. Hart maintained his stoic demeanor until that night, when it came time to transport him to the State Prison. He then collapsed into tears, moaning, "Neighbors, don't think of me as a murderer."

From a legal standpoint--not to mention in the opinion of most onlookers, apparently--the case was satisfactorily closed. However, there was one man, at least, who had only begun to fight. Alvin Dunton launched what was to be a remarkable battle as Nathan Hart's Caped Crusader, his champion, his knight in shining armor.

Two weeks after Hart's conviction, Dunton fired the first shot in his campaign. He wrote a letter to the "Camden Herald," making his case that Albion Meservey, not the convicted man, had written the anonymous letters. He had, Dunton asserted, been "deceived" into telling the Grand Jury that the missives were sent by Hart. He claimed the log book that had been used to compare the handwriting of Hart with the letters had been deliberately tampered with. Dunton stated that he had been tricked into believing certain items in the log book had been written by Hart, when they really were the work of Albion Meservey.

That same newspaper carried a rebuttal by Albion Meservey. While he naturally vigorously denied Dunton's charges against him, he also stated that he believed Nathan Hart was innocent. Albion and his wife followed this up by bringing a libel suit against Dunton. In fact, the inability of anyone on this earth or above it to shut the mouth of Alvin Dunton meant that Albion rather got into the habit of suing the Professor of Penmanship. Meservey was awarded not one, but two judgments against Dunton in 1879. The following year, the two adversaries again met in court, due to the Professor's insistence on telling the world that Meservey was the real killer. Dunton's defense was simply to say that what is true could not be libelous. This jury also found for the plaintiff. However, it does not seem that Meservey was ever able to collect any of the financial judgments made against his adversary.

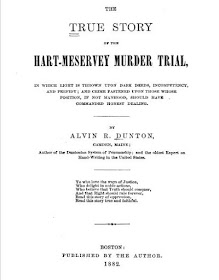

Dunton was, if nothing else, a fighter. His legal defeats merely inspired him to put his case against Albion Meservey into a book. His "The True Story of the Hart-Meservey Murder Trial"--all three hundred pages of it--was self-published in 1882. Dunton painted a picture of a grand conspiracy that makes the various theories about the JFK assassination look like so much child's play. In Dunton's mind, virtually everyone in New England--from Clara Wall to the jurors to the judge to the prosecution's handwriting experts were banded together in a deliberate attempt to frame poor, innocent Nathan Hart for a crime committed by the dastardly Albion Meservey. Dunton showered personal insults on virtually everyone connected with the case. Lines such as "Sly Merrill, do you know where you were when all the anonymous letters were mailed?" and "Staples [the County Attorney,] do you know any sin in the catalogue of crimes that you are not guilty of?" filled the pages. One juror was described as "a stool-pigeon, a courthouse bummer, a priest, quack and pettifogger all combined in one." He even made disparaging remarks about the personal character of the murder victim, Sarah Meservey.

As crime historian Edmund Pearson remarked bemusedly, "I wonder if anyone ever succeeded in comprising so much actionable matter between one pair of covers." It is now an extremely rare book, for the simple reason that, as the "St. Paul Globe" noted in 1901, "For twenty years certain parties have been engaged so sedulously in destroying the books that it is scarcely ever that one is turned up."

Alvin Dunton, however, was fated to be one of the untold millions who spend great energy on causes that were doomed to fail. Five years into his sentence, Hart died of "malignant jaundice," aged only fifty-four. Among the mourners at his funeral were both Alvin Dunton and Albion Meservey.

Garrulous crackpot though he may have been, could Dunton have been on the right track? Was Nathan Hart, as he and his wife never ceased to assert, innocent of all wrongdoing? Or, did Hart kill Sarah Meservey, with someone close to him--possibly Albion Meservey--writing the anonymous letters in an effort to exculpate him? Or was Hart, as the jury in his case ruled, the man responsible for both the murder and the letters?

We will never know for sure.

If you are at all familiar with this blog, you can guess which scenario we will be discussing.

One of the loneliest spots in this lonely village was the house of Captain Luther Meservey and his wife Sarah. They lived at the far end of town, surrounded largely by open spaces. There were only two other homes in the area, and they were in no close proximity. Especially at night, it would not have been a desirable residence for anyone with sensitive nerves and an active imagination.

Sarah Meservey seems to have had neither of those qualities. The thirty-seven year-old was, from what little we know of her, a practical, capable sort well able to fall back on her own resources. She took her mariner husband's frequent long absences with equanimity. When Luther went out to sea in October of 1877, leaving his wife to face a winter alone, (the couple was childless,) there is no reason to think either faced the prospect with any particular trepidation.

Sarah's quiet life went on as usual until December 22. On that day, a neighbor woman came by her home for a short visit. That evening, Sarah walked to the village post office to collect her mail. A young girl named Clara Wall accompanied her for part of this errand.

This seemingly inconsequential act earned little Clara her own footnote role in Tenants Harbor history. Because, as it turned out, she was the last person known for sure to see Sarah Meservey alive.

After picking up her letters, Mrs. Meservey simply vanished from sight. For days, then weeks, no one in Tenants saw any sign of her. What is even stranger is the fact that no one in the village seemed to find this at all odd. There is no record of anyone expressing the slightest concern, or even curiosity, about her whereabouts. This tiny, cocooned village had one of its members--a woman well-known to all, and who made regular public appearances--suddenly drop out of sight without anyone so much as raising an eyebrow. For every student of this murder, that indifference is one of the most baffling aspects of what would prove to be an unusually weird case.

It was not until January 29 that questions began to be raised about Sarah Meservey's long absence. Albion Meservey, a cousin of Sarah's husband, went to visit the local burgomaster, Whitney Long. Albion confided to him that no one had heard anything from Mrs. Meservey for quite some time, and, well, perhaps some kind of investigation should be made.

The two men, accompanied by another Tenants resident named Frederick Hart, went to Sarah's house. The shades were drawn, and the place was ominously cold and silent. All the doors were locked, but they found a back window that could be pried open. We do not know what the men might have expected to find when they climbed into the house, but the result of their search probably exceeded even their worst fears. Nothing unusual was found until they entered a spare bedroom. That room was covered in bloodstains. The furniture was disordered. And lying on the floor, wrapped in a blanket, was the dead body of Sarah Meservey.

Her death had been a particularly violent one. Her body was covered in bruises and wounds, suggesting a desperate struggle. Her arms had been pulled behind her head and tied together with a fishing line. Then she was strangled with her own scarf. She was fully dressed and still wore her walking boots, indicating that she was assaulted immediately after her return from the post office three days before Christmas. Blood was also found around the kitchen door and in the sink, indicating that the killer had washed his/her hands there.

Found near Mrs. Meservey's body was a semi-literate note. It read, "i cam as A Womn She was out and i [waited] till she Come back, not for Mony but i kiled her." Nearby were some used matches. They were of a type not used by the Meserveys. Investigators also found a crumpled, bloody paper collar, presumably torn off the killer during the struggle. Even though nothing appeared to be missing from the house, the working hypothesis was that Sarah had interrupted a burglar, who then overpowered and killed her. The note was presumably left as a clumsy red herring.

Nearly three weeks after Sarah's body was discovered, her husband came ashore from his voyage and returned to Tenants Harbor, completely ignorant of the tragedy that had taken place during his absence. He and his wife had been a devoted couple, and when the captain learned the gruesome news, he was devastated. He had no idea who might have done such a brutal deed.

On February 19, one of the Meservey's neighbors, Mrs. Levi Hart, received a very strange letter, as poorly written as the note left by Sarah's body. It was postmarked in Philadelphia. The letter read: "i thought i would drop you A line to tell your husband to be careful how he conducted things about Tenants Harbor cause if he dont he and a good many others of the men will get A ounce ball put threw them for tell them that it is no use trying to catch this chap for he will not be caught--so be careful who you take up in st George you shall hear from me again in three months." It was signed, "D.M." Enquiries failed to reveal who might have sent the note.

Local gossip, evidently based on private reasons unknown to us, quickly fixated on one man as the likely killer of Sarah Meservey. On March 8, he was arrested. The accused was another sea captain, Nathan F. Hart, who was Sarah's nearest neighbor. Hart was described as a "pretty hard character," but other than that vague description, it is hard to say why so many were so willing to believe he was a murderer. A self-described "handwriting expert," a penmanship teacher named Alvin R. Dunton, believed items Hart had written in a log book matched the handwriting of the anonymous messages. Hart was known to use the same type of matches found near Sarah's body. Flimsy though this evidence sounds, it was enough for a Grand Jury to order that Hart stand trial for murder.

Whoever the writer of those mysterious messages may have been, he kept up his sinister correspondence after Hart was put in prison. On May 17, another Tenants resident named Mahala Sweetland was the recipient of yet another letter, this one sent from Providence, R.I. It was the longest and creepiest of them all. As a classic exercise in psychopathology, it is worth repeating in full:

Take time and read this before you give it up.

Sarah Meservey murder

Mrs. Sweetland. As you ar a woman that i knew would stand reading this letter i used to live in St. George once and knew a good many people--i haven't been there much for 20 years but i had a reason to visit there last winter as as you no doubt [illegible] I intended to wright to Chas sums or deacon long levi Hart of some of them men that I never liked but as i wanted all to know the truth i thought you would be a good one for that. i shall wright more this time than i did before as i think it will be my last or at least for 10 ys— and as a man of my word i will wright another as the last one dicnt satisfy the people—i think this will satisfy them that they haven’t got the man with in there reach that did the deed —and i am going to tell them some of what i have done and of what i am going to do—i am 1 of the hardest hearted of human men of the human white race living and if god lets me live 10 years longer i will be satisfied to die then—i am a man from 25 to 75 years old once i was a good man when i had a father and a mother but they have both been taken from me one was murdered and the other almOst the same it turned my prays for that i was used to praying for i had good Christian folks but it turned my prays to revengefull ones so i started out went to sea and from then ilearned to swear, steal and to kill—i have been Capt and Mate and i have done some ofl hard things but i am bout done goine to sea now ——all i want is revenge on people that has harmed me and is going to i dont blame people for wanting to get me if they can but they have got to work don’t forget that friends—now i will will tell you why i happened a longe St George last winter— long time Ago I was stopping in St. G. and iwcnt with S. Meservey a little and not knowing muteh A bout her i tried some of my natrouls Cappers on her and the result was a slap in the face and told to get or she would take the shirt bosom from me and i got but i told her that she would see the time that i would do as i liked and that is why I have waited this only to see if she had ever told any body A thing A bout it but i think i am pretty safe on that part And you gave me good time to make every other thing safe by letting her lay in the house so long ——i went to the house to fulfill my promise to get her money to kill her and set the house on fire but i had more work to do than iexpected—was in a schooner at the time i happened there in some part of [illegible] At dusk and at 7 o’clock i met her face to face in her Cook room and before she had time to scream i give her a gentel tap on the starboard brow and she fell to the floor senseless i tied her hand and legs picked her, up and laid her on the bed in the room you found her—then i lit the lamp turned it low locked the door put the Curtains down to kill the light and inafew minets she came to her cencis i asked her if she remembered me and remembered what i once wanted and she fetched a scream and i cought her by the throat but she schreamed so hard that i had to strike her in the head again and then she fainted then i laid her as i wanted to and accomplished my desire She had on double clothing and with some trouble i buttoned them up up again she soon came to a gain and then what little blood and swolcn face she had she count scream but could whisper She asked me for some water the first thing and i found her some water bathed her face cleared her throat so she could talk quite plain but she was pretty smart for she was feeling me on her strength i then asked her for her money and she said i will give you all will you let me live and of course I told her yes She told me where it was where no persons would think of looking it was in a place in the house that was fastened up so that it had to be opened with an ax So i left her on the bed to go find the place all as she had explained it to me but let me say threw my carelessness i left her on the bed with her hands tied before her and while looking after something to pry open the place for there wasent an ax or any other tool in the house i herd a noise up in the cook room i went up her loose and out standing up tring to open the door i will say here she must chawed the line in too and had more strength than i suposed she could have but i caught her dragged her back into the room shut the door and there is where the squabble commenced i undertook to tie her again but she was to strong She fought like a tiger she would Break the cod line as fast as i would get it on her hands then we was in the dark and i would keep her under me of course she would take to screaming and if all the people hant been deaf or bout dead they would have herd her 1-2 mile iwonld then threaten to shoot her if she didn’t stop but she seemed to know my mind for i didn’t entend to kill her till i got the money so that didnt scare her eny and i had to haul all the clothes of the bed to pile over her head to kill her voice for i never saw sutch a voice in my life but I counkqued her at last but I dont think I should if in a noughts the things that came of that had happened to be her cloud i tried to choke her with the cod line but i count for as fast as i would get it round her neck she would get her hands between her neck and line and break it and i count make her give up eny how itried—i told her once if she didnt stop her nois that i would stab her to the hart and if she had eny thing to say or to leve behind she had better say it She told me where there was some more money if i Would let her live She said it was luther's money and where it was but if i only got what she told she had i would leve until he had and she called me by name and says kiss luther for me and lay me on my bed in the room next to the road so i told her i would send him a kiss that i took from her bloody lips So tell him here is the kiss (*) but to lay her on the bed that she desired to be laid on I count for she was gaining strength all the time and i knew that she would scream so they would hear her eny body that past by—but if one 6 or 12 had come to helped her i should have showed them good play before they would have captured me for I had what i knocked her down with —1 ounce ball , shooter 2—7 shorts pistols and a dirk knife but it was getting late and i had to be getting a board so not to rais suspicion where i was gone to for i expected to hear from my works by the next day so she was growing stronger all the time so i got hold of her cloud and concluded to choke her to deth instid of stabbing her i had to stop her nois but i was as long as 1-2 hour before i could get it round her neck and then i didnt get it altogether round her neck but i got it so at last that i got a couple of turns a round her neck and arms and i got one square pull and one square knought a gain you bet and she didnt breathe more than two times and i got up i had no matches nor could i find eny and i was a nasty mess my coat vest and shirts was soked in blood by her hands hanging around me and my pants was wet threw to my skin draws and all —and i had cut my overshoes all to peaces on a looking glass that was setting i one part of the room and ihad lost my gloves and hat but it was 11 o’clock and i had to be going i got up felt around the room for bout 10 minutes then i went out washed myself some and took the stick from of the top of the cookroom window went out and got as fast as i could get with out hat gloves or Eny thing but before the next morning i had got all washed up burnt up my bloody clothes got the buttons sunk them in 18 fathoms of water and had 3 hours good sound sleep but i expected to hear it out cry of my work and that i why i left that not saying that i went there as a woman for i thought that you mite think that it was the rawley woman the old lady but things went on smoothly nothing was mistrusted of me doing eny thing for i looked out and not let her scratch or bite me and i never lost a teaspoon ful of blood and i never see so much blood come from eny body in my life and and i have put the dirk knife to more than 1 persons hart i should think there was a large buckett ful and all from her hed from 1 scar on the starboard brow and the rest out of her mouth and noes—well as soon as we got in i left as i herd nothing of the a fair and i got for St George as soon as i could get there after my hat and money i stopped one night to make sure nothing had been suspected and the 15 night from the time i first entered i went to the house at 11 o’clock went into the barn and got the ax and pried the window open it was sweled down hard i went in lit the lamp that i set on the table and went into the room where she was found my things went down and got my $1100.00 that was nicely packed in a little box went back where she was give her a kick in the ribs and told her i had got all i wanted of her and if she wanted eny thing more i was ready to give it to her i gave her a sweet smile and left her went out of the window Concluded not to burn the house and what other little money there was in the house—the first i herd of her being found or to find out mutch was to Bristol abroad of the schooner levie hart that a jones fellow told me all he knew about it the next i herd they had 2 or 3 boys up for trial well let me tell you if a pretty large boy had undertaken to done what i did you would have found him, where you found her if she aint taken care of him and came and told you her self for i would rather take my chance with levi hart or Steve hart open handed than to fight one like her again but i guess i wont tell you eny thing more about her unless you want to know very bad and if you do offer a handsome reward and i will tell you and i will get the money and you will never find me dont forget that fools if the State County or town has got millions of $ to spend on my case let them start for i am willing to die after i fixe a dozen or so as i want and intend to—livie hart for one in less than 1826-1-4 days this is his destiny i shall be in St George -—if i can i shall steal his horse and gig and if i cant i can furnish one my self i have been in Philadelphia i have been in New York in portland Boston and other places where there has been St Georgers—and found out what the people intend to do with me—i shall tie him heels upward so his bed will smell dust drive at a moderate rate once round the squair hitch the horse to a tree leave him for somebody to find in the morning and to those who wants to out me in peaces i shall find them out and cut their tongue out and let them live as long as they will and so i say to all the folks in St George who helps and beleves Condemns a innocent person for i know when you have the rong one for i personally and god only knows who did that deed of murder do there is Capt John bickmores property i long to get to work there and i went up to the New house and had a mind to set it on fire but i thought it would be insured on so they wont lose much but dont forget they have a maiden daughter and a good many others that some of these days will pay the det all the det they owe for all i want to get is three more men like my self or like what you think hart is for if he can do what you suppose he has done for i herd he went into the house and looked at her and helped take her out of the house in the middle of a crowd—if he can do that he is one of the men i want for i could do that as easy as i can wink i herd if they got the wright man they was a going to put him in the toom with her i could have staid there one month and come out fat—So i say to all that they better make up to that man all that he loses and more to give him as good a schooner as you have got—for the rong you have done to him—And to you Mrs Sweatland for your daughter’s safety show this letter to his wife before you give it up—then Copy it if you want to and send this to head qrs—for i sepose they will want to preserve it for a while the last time i was in philadelphia i stood as near the man that offered 500 and 1000 dollars reward for knowledge of that letter—that i could have put my knife to his hart without stepping once but l dient want as little a sum as that nor him as long as he doesnt try to harm me —-and for sending that letter to philadelphia and to a man i think that knows for his interest not mine has and will hold his tongue but i will tell you as a man of my i dient send it from St George and i would give you this in short hand or enything if i had thought that you could have found it out—for i thought that you would make as bad mistake as the expert did when he pronounced my writing som body’s else he would find some difference between this and the other and my log books if he could see them i live in the state of New York if you would like to know and i have had some of as smart ditectives on my truck as there was in New York City and had them along side of me and talked of the affair and bit my lips till the blood come from them to keep from laughing at the prospect of getting me—well i have been three hours wrighting to you and more i will mail it this day and the present hour— So i say in closing dont forget that i am a man of my word i sepose you would like for me to give you a little course wrighting in let you know that i wrought the other so i will wright levi hart.

Was this letter genuinely written by Sarah Meservey's killer? Or was it written by an ally of Nathan Hart, in an effort to give him an alibi? Whichever may have been the truth, it is certainly one of the most chilling messages associated with a murder case.

Nathan Hart stood trial in October 1878. A reporter in the courtroom was not impressed with the defendant, describing him as "wearing a smirk that gives [his lips] a crafty, treacherous cast that is not prepossessing." Hart calmly, stubbornly continued to insist on his innocence. His demeanor was "calm and cheerful all the time."

The prosecution's case could be summarized thusly: Mrs. Meservey's killer was skilled at tying maritime knots, and Hart was a sailor. His proximity to Sarah's house gave him the opportunity to know when she was absent. He attempted to rob her, and when she surprised him by her unexpectedly early arrival, Hart felt he had no choice but to kill her. He had no alibi for the night of the murder. He showed evidence of knowing certain details about the murder before they were publicly revealed. Before the body was found, Hart told friends he had dreamed that Sarah Meservey was strangled to death--surely a guilty conscience manifesting itself. A brother of the dead woman recalled that on the day Sarah's body was discovered, Nathan Hart told him that he, Nathan, had known "she was in there dead, all the time." The State presented several handwriting experts who asserted the anonymous letters were in the defendant's hand. Hart, they argued, wrote these letters and arranged to have them posted in various cities in an attempt to draw suspicion away from himself. A Warren Hart testified that a few months before the murder, he was "joking about women" with the defendant and his wife. Mrs. Hart jocularly mentioned an occasion when Sarah Meservey had slapped Nathan's face and pulled out his shirt bosom--presumably when he became a bit too frisky with her.

In response, the defense asserted that the handwriting "experts" were simply all wet. Their client did not write the letters. The various statements attributed to him could hardly be called proof of guilt. Hart's wife and stepdaughter testified that Nathan had been at home all day December 22. A Mr. Whitehouse stated that he saw the defendant at his house around 8:30 of the fatal night.

Alvin Dunton, who had testified for the State at the Grand Jury, now did an about-face by appearing as a defense witness. After studying all the relevant documents, he now believed that Albion Meservey had written the letters. Dunton's appearance on the stand was the unquestioned dramatic high point of the trial. A local newspaper described with unmistakable delight how "Witness here swooped down from the stand on the jury, and inundated them with a stream of eloquence concerning his theories. The sum of all was that Albion K. Meservey wrote the brown-paper note, the Philadelphia letter, and the first five pages in the Log Book No. 1. Witness bobbed from the Judge to the jury like a sewing-machine shuttle, his tongue meanwhile going with a speed that would have left even Miss Pulsifer's [a local court stenographer] facile pen behind, we fancy, had an attempt been made to report him. While Mr. Dunton was thus disporting himself, the audience relapsed into social enjoyment, and the courtroom was like an evening party...Finally, Mr. Montgomery told counsel for State to cross-examine. But witness said he hadn't got through with his testimony..."

It was quickly becoming clear that Alvin Dunton was what every truly great murder case needs: a colorful crank.

Nathan Hart himself then took the stand. He reiterated that he had been at home all the evening Sarah Meservey was murdered. He stated that his dream about Mrs. Meservey had taken place after her body was discovered. He denied that he had urged that her house be searched. He did not write the anonymous letters, and he did not know who had. He had nothing whatsoever to do with Mrs. Meservey's death.

On paper, at least, the evidence both for and against the defendant's guilt appears irritatingly skimpy. However, this did not prevent the jury from returning a verdict of "Guilty of murder in the first degree." The judge sentenced him to life imprisonment. Hart maintained his stoic demeanor until that night, when it came time to transport him to the State Prison. He then collapsed into tears, moaning, "Neighbors, don't think of me as a murderer."

From a legal standpoint--not to mention in the opinion of most onlookers, apparently--the case was satisfactorily closed. However, there was one man, at least, who had only begun to fight. Alvin Dunton launched what was to be a remarkable battle as Nathan Hart's Caped Crusader, his champion, his knight in shining armor.

Two weeks after Hart's conviction, Dunton fired the first shot in his campaign. He wrote a letter to the "Camden Herald," making his case that Albion Meservey, not the convicted man, had written the anonymous letters. He had, Dunton asserted, been "deceived" into telling the Grand Jury that the missives were sent by Hart. He claimed the log book that had been used to compare the handwriting of Hart with the letters had been deliberately tampered with. Dunton stated that he had been tricked into believing certain items in the log book had been written by Hart, when they really were the work of Albion Meservey.

That same newspaper carried a rebuttal by Albion Meservey. While he naturally vigorously denied Dunton's charges against him, he also stated that he believed Nathan Hart was innocent. Albion and his wife followed this up by bringing a libel suit against Dunton. In fact, the inability of anyone on this earth or above it to shut the mouth of Alvin Dunton meant that Albion rather got into the habit of suing the Professor of Penmanship. Meservey was awarded not one, but two judgments against Dunton in 1879. The following year, the two adversaries again met in court, due to the Professor's insistence on telling the world that Meservey was the real killer. Dunton's defense was simply to say that what is true could not be libelous. This jury also found for the plaintiff. However, it does not seem that Meservey was ever able to collect any of the financial judgments made against his adversary.

Dunton was, if nothing else, a fighter. His legal defeats merely inspired him to put his case against Albion Meservey into a book. His "The True Story of the Hart-Meservey Murder Trial"--all three hundred pages of it--was self-published in 1882. Dunton painted a picture of a grand conspiracy that makes the various theories about the JFK assassination look like so much child's play. In Dunton's mind, virtually everyone in New England--from Clara Wall to the jurors to the judge to the prosecution's handwriting experts were banded together in a deliberate attempt to frame poor, innocent Nathan Hart for a crime committed by the dastardly Albion Meservey. Dunton showered personal insults on virtually everyone connected with the case. Lines such as "Sly Merrill, do you know where you were when all the anonymous letters were mailed?" and "Staples [the County Attorney,] do you know any sin in the catalogue of crimes that you are not guilty of?" filled the pages. One juror was described as "a stool-pigeon, a courthouse bummer, a priest, quack and pettifogger all combined in one." He even made disparaging remarks about the personal character of the murder victim, Sarah Meservey.

As crime historian Edmund Pearson remarked bemusedly, "I wonder if anyone ever succeeded in comprising so much actionable matter between one pair of covers." It is now an extremely rare book, for the simple reason that, as the "St. Paul Globe" noted in 1901, "For twenty years certain parties have been engaged so sedulously in destroying the books that it is scarcely ever that one is turned up."

Alvin Dunton, however, was fated to be one of the untold millions who spend great energy on causes that were doomed to fail. Five years into his sentence, Hart died of "malignant jaundice," aged only fifty-four. Among the mourners at his funeral were both Alvin Dunton and Albion Meservey.

Garrulous crackpot though he may have been, could Dunton have been on the right track? Was Nathan Hart, as he and his wife never ceased to assert, innocent of all wrongdoing? Or, did Hart kill Sarah Meservey, with someone close to him--possibly Albion Meservey--writing the anonymous letters in an effort to exculpate him? Or was Hart, as the jury in his case ruled, the man responsible for both the murder and the letters?

We will never know for sure.

Friday, January 15, 2016

Weekend Link Dump

This week's Link Dump is sponsored by the International Federation of Cowboy Cats.

Who the hell owns Antarctica?

What the hell is buried under Antarctica's ice?

Who the hell was El Mariachi? And who killed him?

Watch out for those terrorist squirrels!

Watch out for those diabolical rabbits!

Watch out for those rose petals!

Watch out for Dyatlov Pass!

The murder cottage of Joe the Quilter.

This is one old medical cure I can get behind.

The dangers of mispronouncing "Newfoundland."

The colorful career of Nellie Bly.

That time Ambrose Bierce denounced the waltz.

Ghostly estate planning.

A frozen ghost.

An unusual ancient prosthetic leg.

When you come across the phrase "amateur anatomist," you know the good times are about to roll.

Annette Kellerman, Australian mermaid.

"Know I died happy": a message from beyond the grave.

The online lynch mobs are now turning their attention to cartoon characters.

More pushing-back human history.

Some Newcastle eccentrics.

Bookstore chat.

Some facts about the Four Georges.

Some people have a heart of stone. Others have a heart of gold. At least one woman had a heart of soap.

Nikita Khrushchev visits America. Hilarity ensues.

The tragic case of the Boy in the Bubble.

Jack Graham, aerial mass murderer.

The last will of Louis XVI.

A fairytale castle in Belgium.

They've confirmed the site where the Salem witches were executed.

My new ambition in life is to be a professional goat snuggler.

I wouldn't mind driving a touring bee van, either.

The "world's most remarkable globe."

A look at hospital ghosts.

A servant murders her mistress.

The history of Plough Monday.

The history of "love suicides."

19th century fortune telling.

Quote of the week: "As I look around now, I don’t see much except for squirrels."

Dr. Slade, a medium with a very curious history.

If you're in the mood for some really creepy recordings, here you go. Warning, though: Once heard, that 9/11 call from the Twin Towers can't ever be unheard.

The evolution of nursing.

18th century bedding.

18th century traffic jams.

I've never cared for Hemingway's writing. Turns out he was an even worse spy.

Dr. Beach is wondering why there aren't more cellphone videos of levitating saints, and, frankly, so am I.

The history of the influential Marylebone Free Library.

If you're at all familiar with the Victorians, you won't be surprised that their exercise machines were scary as hell.

There are no longer any living survivors of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

"Britain's Pompeii."

"A very melancholy circumstance," 1800.

The problem with medieval dwarfs.

The Temple and the French Revolution.

José Félix Trespalacios, Governor of Texas.

Charles Macquarie's tough times in early Australia.

The duel that turned into comic opera.

19th century pet rabbits.

And, finally, this week in Russian Weird: Yeah, sure, blame it all on the reindeer.

This week in Russian Weird, Part Two: Were they behind the assassination of Franz Ferdinand?

That's it for this week. Tune in on Monday, when--as was decided by an impromptu poll I took on my Facebook page--we'll be going down that popular path of mysterious murders. (Have no fear, you fans of kidnapped corpses; that'll be coming soon.) In the meantime, take it away, Gram and Emmylou:

Wednesday, January 13, 2016

Newspaper Clipping of the Day

This tale of Windy City Witchcraft appeared in the "Chicago Tribune" for February 24, 1919:

Witches, brooms, incense, burnt salt, a lamb's heart with new pins stuck in it and burnt, rusty nails, plots, threats, a will, a priest, a dead man, a dead woman, and three live women. These are all mixed up in a strange story that a reporter for the Tribune tried to unravel yesterday.

Today, William L. Sehlke, 5033 South Loomis street, a masseur, says he will go to the Stockyards police court and ask for warrants for Mrs. Mary Vogel, 50 years old, a nurse living near Fifty-second street and Princeton avenue, who he says practiced witchcraft, and Miss Augusta Wilke, 21 years old, 5022 South Loomis street, an assistant forewoman in the plant of Armour & Co., and his sister-in-law, whom he and his wife term an understudy for Mrs. Vogel.

Sehlke says he wants to have them put under peace bonds, as he fears they may harm him and his family. A lot of talk has started through the neighborhood following the death on Feb. 2 of Mrs. Mary Sleeth, 22 years old, 5009 Bishop street, wife of Victor Sleeth, an assistant superintendent for Armour &Co.

Mrs. Sleeth died of consumption and was a sister of Mrs. Martha Sehlke, wife of Sehlke, and Augusta Wilke. According to Sehlke and his wife, Mrs. Vogel was called to attend Mrs. Sleeth by Miss Wilke, and while Mrs. Vogel was ostensibly nursing the sick woman for a month she was "practicing witchery" over her.

She was ordered out of the house by the Rev. Father Phillips of the Franciscan Fathers of St. Augustine's church, Fifty-first and Laflin streets.

"Yes, I went over to the Sleeth home and found Mrs. Vogel there,"said Father Phillips yesterday. "She was burning salt in the oven and had some incense burning in the rooms. She was making motions with her hands, and I told her to get out, and she did."

Sehlke and his wife told the reporter an amazing story.

"My sister, Augusta, who is a forewoman over Mrs. Vogel, called Mrs. Vogel to attend my sister," Mrs. Sehlke said. "Mary would tell me of all the doings when the two were not around. She said Mrs. Vogel claimed I was a witch and was poisoning Mary for the benefit of two other women, Mrs. George F. Hellman, 3531 West Sixty-fifth place, and Mrs. Marian Sleeth, a widow and sister-in-law of Sleeth. Mrs. Hellman and Mrs. Sleeth were also supposed to be witches.

"Mrs. Vogel was burning salt and incense. She got a lamb's heart and put some new pins in it and burned it. This was to find out which of us 'witches' would be around that day and to cast a spell over the one that would come. On Jan. 23 I went over to the home of Mrs. Sleeth and found I had been locked out.

"They got my sister to make some kind of a will leaving about $1,200 insurance to her parents, two sisters, and her daughter Esther, 7 months old.

"Two weeks ago my brother-in-law, William Wilke, 2507 West Forty-seventh street, was sent over here by them," said Sehlke. "He died last Wednesday.

"I think that woman has slandered us enough, and I am afraid she and Augusta will come over here and start something. I am going to get out warrants for them."

Nobody would answer the bell at the Wilke home last night. Efforts to locate Mrs. Vogel were made in vain.

I haven't been able to find any more about this diabolical feud, which is a great pity. It sounds like this crowd could've supplied me with years' worth of blog material.

Monday, January 11, 2016

The Awful Greatness of the Cherry Sisters

"Bravery is its own reward."

~Reputed motto of the Cherry family

In 1896, New York stage impresario Oscar Hammerstein (grandfather of the famous librettist) was in serious financial trouble. He was deeply in debt, thanks to putting on several unsuccessful operas in a row.

It occurred to the producer that since his efforts to present the public with the best entertainment had been a colossal flop, why not try giving them the worst? This was a brainstorm that led to a memorable episode in the history of American entertainment. He hired a hitherto little-known vaudeville act, the Cherry Sisters.

The five siblings--Ella, Elizabeth, Addie, Effie, and Jessie--were raised on a small, ramshackle farm in Iowa. By the mid-1880s, both their parents were dead, and their only surviving brother, Nathan, had abandoned the farm for parts unknown, leaving the girls alone in the world. They spent a few years managing the farm, but then their ambitions became a good deal loftier. The girls always had a fondness for skits and recitations, and in 1893, the siblings, who ranged in age from 29 to 21, decided the stage would be their new career.

They rented an opera house in Marion, Iowa. The sisters handled every aspect of the production, right down to designing and distributing handbills advertising the show. The show was entirely characteristic of their later, more famous performances. They appeared on stage with their hair colored an eye-catching yellow--courtesy of some spare paint they had handy. Effie sang a solo. Jessie played the harmonica. Ella donned blackface and sang a comic ballad.

It is not clear whether the good citizens of Marion had a well-developed sense of humor, or they were extraordinarily starved for entertainment, but in either case, the sisters were a great hit. Their performances were sellouts. They followed this triumph with a stint at Greene's Opera House in Cedar Rapids.

This more cosmopolitan audience was not as enthused as the hometown folks. The "Cedar Rapids Gazette" summarized the evening with more honesty than tact: "Such unlimited gall as was exhibited last night at Greene's Opera House is past the understanding of ordinary mortals. They are no doubt respectable girls and probably educated in some few things, but their knowledge of the stage is worse than none at all...if some indefinable act of modesty could not have warned them that they were acting the parts of monkeys, it does seem like the overshoes thrown at them would have conveyed the idea in a more substantial manner...But nothing could drive them away and no combination of yells, whistles, barks and howls could subdue them. They couldn't sing, speak or act. They simply were awful. When one of them would appear on the stage, the commercial travelers around the orchestra rail would start to sing, the orchestra would play and the entire audience constituted the chorus. At one minute the scene was like the incurable ward in an insane asylum, the next like a Methodist camp meeting. Cigars, cigarets, rubbers, everything was thrown at them, yet they stood there, awkwardly bowing their acknowledgments and singing on."

Whatever the Cherry quartet (Ella dropped out of the group early on,) may have lacked in talent, they made up for it with courage and self-esteem. According to report, each of the ladies thought she herself was immensely talented, and the negative audience reaction was the fault of her less gifted siblings or jealous rivals. The Cherrys stormed the "Gazette" offices and insisted on a retraction to these published insult. The editors--who knew a great opportunity to have a bit of fun when they saw it--sportingly suggested the offended women write their own rebuttal.

The "retraction" composed by the sisters gives some flavor of their literary and artistic talents. It read, "The Cherry Sisters Concert That appeared in the Gazette the other evening was initily a mistake and we take it back The young ladies were refined and modist in every respict And their intertanement was as good as any that has been given in the city by home people. The noise and tumult that was raised in the house was not done as stated by the Cedar Rapids people but by a lot of toughs that came down from marion with the intention of creating a disturbance."

The Cherry sisters still felt the wrong done against them had not been avenged. Addie filed a libel complaint against Fred Davis, editor of the "Gazette." The newspaper cheerfully suggested the trial take place during the aggrieved sisters' upcoming show. The popular suspicion that both sides in the dispute were staging a mutually advantageous publicity stunt was probably not unfounded.

The "trial" took place in March 1893. It was, without doubt, one of the most raucous tribunals on record. The audience was delirious with joy at the utter ridiculousness of it all. They shouted, whistled, blew horns, tooted kazoos. Before long, the Cherry Sisters could not be heard at all above the uproar, which considering their talents was possibly just as well.

With such popular support, the sisters naturally won their case. The erring Davis was ordered to manage the Cherry farm while the sisters were on the road. But that was not all. It seemed the court wanted to impose a life sentence. "We further find that when the said Cherry Sisters shall return from their triumphal tour, the said Davis shall submit himself to the choice of the said sisters, beginning with the eldest, and the first one who will consent to such an alliance to that one shall be then and there joined in the holy bonds of matrimony." (In truth, none of the sisters ever married, or, as far as is known, had anything remotely approaching a romantic relationship.)

The Sisters next appeared at Davenport's Burtis Opera House. Their reputation had preceded them. The local paper printed a notice warning their fans that guns were to be left at the theater door, and that all rocks larger than two inches in diameter were forbidden. After the performance, the same paper enthused that it had been an "unutterably rank show."

When the sisters took the stage in Dubuque a few months later, the audience reaction blossomed from mere rowdyism into anarchy. At first, their fans settled for hurling the usual vegetables and tin cans at them. But then, someone took the unusual step of spraying the sisters with a fire extinguisher, forcing them to flee backstage. One of the Cherry ladies--history is unclear about which one it was--retaliated by marching back in front of the audience sporting a shotgun. It was looking very much like the sisters would encore with a body count, until she was forced offstage again by a "volley of turnips." Attempts were made to restore order until someone threw a wash boiler onstage, causing a general retreat.

It is a very special theatrical act indeed that can inspire a full-scale riot.

The sisters filed a lawsuit against the city of Dubuque for failing to provide adequate security. This suit failed, but it little mattered. The Cherry women were quickly obtaining a sort of semi-legendary status.

The Cherry Sisters spent more months touring the midwest, and then traveled to New York for their grand appearance at Hammerstein's theater. It is safe to say the audience had never seen anything quite like it. To quote the "New York Times": "It was a little after 10 o'clock when three lank figures and one short and thick walked awkwardly to the centre of the stage. They were all dressed in shapeless red gowns, made by themselves most surely, and the fat sister carried a bass drum. They stood quietly for a moment, apparently seeing nothing and wondering what the jeering laughter they heard could mean...None of them had shown a sign of nervousness, nor a trace of ability for their chosen work."

The ladies opened the show by belting out their unforgettable theme song:

"Cherries ripe boom-de-ay!They performed Irish ballads, more songs of their own unmistakable composition, and a God-knows-what called "Corn Juice." Jessie beat her drum. Their enthusiasm was matched only by their utter absence of anything approaching musical talent. One critic noted that "A locksmith with a strong rasping file could earn ready wages taking the kinks out of Lizzie's voice."

Cherries red boom-de-ay!

The Cherry sisters

Have come to stay!"

The sisters followed this concert with a dramatic skit of their own invention, "The Gypsy's Warning." Addie slapped on a fake mustache in the role of the villainous suitor of Elizabeth. Effie--the gypsy--interrupted them to deliver...well, a warning.

|

| Scene from one of the Cherry Sisters' skits |

The audience could not believe what they were seeing. Once they realized that the Cherry Sisters were not a deliberate joke, they gleefully entered into the spirit of the thing, hooting, heckling, and applauding. And these audience members came back for more. They brought their friends! As had happened with Robert Coates many years before, theater-goers learned that there is nothing quite so exhilarating as watching the worst performance you will ever see in your life. True badness has an epic greatness all its own.

Although the staid "New York Times" groaned that "It is sincerely hoped that nothing like them will ever be seen again," the ladies from Iowa were the surprise theater hit of the season. For the next six weeks, they played to full houses. The audience threw so many vegetables at them that grocers were having a hard time keeping them in stock. Oscar Hammerstein's career was saved.