Thursday, December 31, 2015

A Strange Company 2015

As I did at the close of 2014, I thought I'd do a year-end wrap-up taking a look at the top ten posts from the past year. Just to be different, it had occurred to me to make a list of my innumerable posts that proved to be about as popular as botulism at a picnic, but after some reflection I decided that might be too depressing. For me, at any rate.

I figure there's more than enough Weird in the world to keep this goofy little blog of mine going at least through 2016. I hope at least some of you will continue to be part of Strange Company's strange company, as we look at more disappearances, murders, cats, scandals, cats, ghosts, witches, kidnappings, general bad behavior, and, of course, cats.

So, on with the countdown, starting with 2015's most popular tale:

1. The Horror in Room 1046.

This is one of those murder mysteries that I'm surprised isn't more well-known. The post, incidentally, owes its relative popularity to a link on a Reddit sub. [Side note: If you want to make any blogger really, really happy, share one of their posts on Reddit. Hit-count gold, baby.]

2. Newspaper Clipping of the Day, February 25, 2015.

All hail those Ladies of the Illustrated Police News!

3. A Case For David Paulides.

The tragedy of a small boy's inexplicable disappearance from an amusement park.

4. The Witch of Ringtown.

Witchcraft, hexes, ghostly black cat familiars, and murder...in 20th century America.

5. The Great Trinity Church Hoax; or, Dix Picked For Slick Tricks.

A New York clergyman is the target of a series of increasingly deranged hoaxes.

6. The Adventures of Miss Cora Strayer, Private Detective.

I can't tell you how much fun I had with this one.

7. Newspaper Clipping of the Day, May 13, 2015.

As I said at the time, I was uneasy about posting this story of a grave-robber's dreadful end. It was so macabre, so incredibly gruesome in detail, I thought it could be too much for anyone to read. I feared it might drive all of you away for good.

So, next thing I know it's the 7th most popular post of the year. God love ya, gang.

8. A Disappearance at West Point: The Case of Richard Colvin Cox.

This vanishing of a USMA cadet is one of the strangest missing-persons cases I know.

9. Captain King and the Golden Needle.

This account of the eerie death of a British military officer in Egypt was a particular favorite of mine from the past year--it reminds me of M.R. James' more open-ended stories--so I was pleased to see it make the Top Ten. Usually, my favorite posts on this blog tend to get the fewest hits. Which probably helps explain why I'm a financially-strapped nobody and J.K. Rowling is a multigazillionaire.

But I digress.

10. The Sinister Disappearance of a Film Pioneer.

What the hell happened to Louis Le Prince?

So, there you have the best--or, at least, best-read--of Strange Company 2015. See you in 2016, and may it be a happy, prosperous, and really, really peculiar year for us all.

Wednesday, December 30, 2015

Newspaper Clipping of the Day, New Year's Eve Edition

For this New Year's post, I offer a cautionary tale about the importance of inspecting your prospective bride or groom carefully.

Very, very carefully. From the "Illustrated Police News" for March 23, 1878:

My friends, may you never, ever, have an Illustrated Police News New Year's Eve.

Very, very carefully. From the "Illustrated Police News" for March 23, 1878:

The New Year's festivities at the usually quiet and unexcitable colliery village of Croxdale have been greatly enlivened by the discovery and public exposure of a well-contrived, and cleverly carried out matrimonial hoax.

It appears that for some time a certain very grave individual has been lodging at Croxdale-terrace, and working as a hewer at Croxdale colliery. He is a man past the prime of life--in fact, a grey-haired old chap--but his stylish mode of dressing, jaunty air, and open admiration of the fair sex, have made him quite conspicuous in the neighourhood. Being a regular attender at chapel and class, a constant reader of religious literature, and a very quiet, steady, and inoffensive person, it is not surprising that many of the lonesome widows and ancient spinsters of the locality cast wistful glances at him as they passed him on the road, or sat with him in the chapel. But none of these were to his liking. He wanted a young wife, and a pretty one, but having passed the Rubicon, the girls were shy of his grey head, beard, and whiskers.

Some five weeks ago, however, fortune seemed to favour him, for a pretty young woman looked at him so earnestly one night that he was sure she had been smitten by his appearance. She was in company with a young man who worked next board to him in the pit, but that circumstance only seemed to smooth the way for an introduction to the charmer. The next morning, therefore, "Gentle Johnny," as he is designated, inquired of the young man who the fine-looking girl was that he saw in his company the preceding night. Now, it so happened that the "fine-looking girl" was the wife of the young man, but for a lark he, like Abraham, said she is my sister.

Johnny, therefore, began to praise her good looks and nice manners, and asked his friend if he would mind introducing him to his charming sister. With an eye to further fun the young man promised to help him in the matter, but said he must first see if she was willing to accept him as a suitor, and then he would tell him when it would be most convenient to come to the house.

That night the young man, his wife, and a few friends concocted a plot to hoax poor Johnny, and let the public know that he was already a married man living apart from his wife. Next day Johnny was informed that his attentions would be acceptable, and he could have a first interview that evening, as the old folks were to be from home for a couple of hours. At the appointed time Johnny went to the house, dressed up in his broad cloth and kid gloves, with a grand silk umbrella in his hand. He was duly introduced, and the discreet brother very considerately withdrew, and left them to arrange matters. How Johnny conducted himself during the interview is now the subject of universal conversation at Croxdale.

The "young lady" at first absolutely refused to have anything to do with him, unless he would first shave off his whiskers and beard, which he promised to do before his next visit. She then promised to meet him at a certain hour on a certain night, dressed in a white shawlet, and have a moonlight walk with her devoted admirer. From this time forth Johnny and his "lady love" met regularly, and the couple might have been seen any night on the Darlington road beyond Croxdale, walking side by side, the arm of the swain fondly encircling the waist of his adorable mistress. Johnny was not so deeply smitten, however, but that he noticed some rather strange peculiarities in the manner and behaviour of his charmer. She wore very strong boots, for instance, and walked with a firm, vigorous step, like a female Weston, but she explained that she liked to keep her feet warm, and Johnny acquiesced with the trite remark that when the feet were warm we felt warm all over. Then she grasped his hand at parting with a grip that always brought the tears to his eyes; but Johnny put this to the warmth of her feelings.

Marriage was eventually proposed and the offer accepted. The ring was to have been bought last Saturday, and the ceremony completed by special license. But, alas for Johnny's peace of mind--they took their last walk on New Year's Eve. Johnny on that night was more affectionate and pressing in his suit than ever, but "the lady" reminded him that he would have to go home with her and ask the consent of her parents to the match. Nothing loath, Johnny expressed himself perfectly willing to do so, and the twain at once proceeded to the girl's domicile for that purpose. But the evening appeared to be inauspicious, as there was quite a large party assembled. Johnny, therefore, thought the time inopportune to prefer his request for the daughter's hand.

Not so, however, "the lady," for she stood forth, and informed the company that he had proposed to marry her, and she desired them all to bear witness to the fact, for she was now going to put his love to the test. Saying which, she proceeded to divest herself of her bonnet, fall, gloves, shawlet, gown, and other female attire, and presently stood before them in the form of a strapping potter lad, known as "Queer Tommy." It would be impossible to describe the scene which ensued upon this exposure. Suffice it is to say, that the would-be bridegroom eventually made his escape from his tormentors amid much merriment.

Since the above event was made public "Johnny" has been so unmercifully chaffed that he has threatened several people with personal chastisement; he has sought the protection of the local policeman, and got the viewer to give a general notice that any one interfering with him in future will be discharged from the colliery. It should, however, be known to all men and women, whom it may concern, that he is again cultivating his hirsute appendages, and presents a very grisly appearance in his woeful devastation.

My friends, may you never, ever, have an Illustrated Police News New Year's Eve.

Monday, December 28, 2015

Publicity and Clement Passal; or, A Warning to Authors

It is hardly uncommon--particularly in our exhibitionist, social media-driven, "Look at me! Look at me!" era--to hear stories of authors resorting to unusual and outlandish publicity stunts to promote their books.

However, I defy anybody to top this one.

Clement Passal was a man well-known to the French police in the early 20th century. He was a career thief who, under his favored alias of "Marquis de Champaubert," committed various swindles. He was a determined, ambitious crook, but, alas for him, a largely unsuccessful one. His busy career earned him a prominent name in the Parisian underworld, but not much else.

The 1920s were something of a golden age of the "celebrity gangster." Criminals, if they were just bold and colorful enough, were treated like movie idols. Passal saw no reason why he should not get a piece of this action. In 1929, after serving the latest of his many prison sentences, he decided to write his memoirs. Perhaps the story of his adventures would finally make crime pay for him.

Unfortunately, his book proposal failed to attract much interest. As extensive as his criminal history may have been, it was all too run-of-the-mill to make for exciting reading. It lacked that element of romance and novelty the public wanted in their scoundrels. Passal finally managed to sign a publishing contract, but--as all fledgling authors soon come to realize--he knew that something was desperately necessary to make him stand out in the bookstores.

In September 1929, Passal's mother received several weird and extremely alarming anonymous letters. These messages stated that her son was being held captive by a mysterious organization called "The Knights of Themis." These letters described in graphic detail the various tortures being inflicted on Passal. Similar letters were sent to the newspaper, "Le Matin," giving the remarkable story behind the crime. The writer stated that the "Knights" had kidnapped Passal in order to force him to reveal the hiding place of money he had made through his various swindles. The letters alleged that Passal, far from being just another mediocre petty con man, was in reality a criminal genius who had amassed a secret stash of some 15 million francs. The "Knights," "composed of the cream of society," saw itself as an extrajudicial tribunal, punishing criminals who had, in the opinion of the "Knights," gotten off too easy in the French legal system. The writer promised that other thieves would be dealt with in a similar manner. Passal himself wrote to his mother, confirming his imprisonment by the "Knights," and bidding her a touching farewell, as he was sure the group meant to kill him.

On October 3, Madame Passal was sent the worst letter of all. It informed her that Passal had been buried alive by his bloodthirsty captors. The nameless writer stated that a bad conscience compelled him to reveal this dark deed, "to have [Passal] rescued before he dies." He even included a detailed map showing precisely where the victim was buried. "Le Matin" received a letter from the "Knights" giving every lurid detail of the entombment:

"When the grave had been dug, we once more offered to spare his life if he would cease dissembling, but with no effect. We then took off his shoes, and, leaving only his shirt and trousers on him, we laid him in the coffin which we had made out of a packing case that had been used for carrying upholstery.

"He offered no resistance, and we closed the lid and placed the coffin in the grave, which we then filled in with earth. Until four o'clock in the morning we remained on watch.

"Before burying him we gave him to understand one of us would remain constantly near the spot and at the slightest sound from him would block up the pipe through which he was breathing, although not a soul was likely to pass.

"As a matter of fact, we simply abandoned him to his fate, certain that he would not escape death. We can only conclude from the attitude of the 'marquis' at the last that he was mad, letting himself be buried without showing any emotion.

"Since that is the case with him, he will not suffer. We consider our deed against the 'marquis' virtually complete, and our end attained. It is a good finish to the holidays."

Naturally, the recipients of these blood-curdling messages took them to the police. After a little persuasion--the constabulary was at first inclined to dismiss these letters as a bizarre joke--some officers were sent to the site claimed to be Passal's burial place. They were unsettled to find an area of freshly-dug earth, with a tube sticking up among it. They began to dig, and before long unearthed a crudely-built coffin. And, yes, Clement Passal was inside it.

Unfortunately, they were too late. It was clear from the agonized expression on Passal's face, and the contorted position of his body, that he had died a horrifying death from asphyxiation. A number of chocolate bars were found in the coffin, indicating that whoever buried Passal expected him to be alive for some time. However, the breathing tube placed in the coffin had not provided him with an adequate supply of air.

The police investigation into Passal's dreadful death soon led them to a friend of his, an ex-convict named Henri Boulogne who was now, significantly, working as a grave-digger. After a lengthy interrogation, the whole story came out. In mid-September, Passal had enlisted him in a little scheme he had devised. His aim was "to attract public attention to himself in order that he might then be able to publish sensational memoirs."

Passal typed out a number of letters, which were to be posted to various people. He and Boulogne built a coffin. On September 30, he spent eight hours in the box, as a test of whether he could safely stay in it for a prolonged period of time. The next evening, he led his accomplice to a spot in the wood at Verneuil. A large grave was dug. Passal got into the coffin, which Boulogne then closed and buried.

Boulogne stayed by the grave for some fifteen minutes, to make sure that Passal was able to breathe. After the "victim" reassured him via the tube that he "was quite all right," Boulogne returned to Paris and, as he had been directed, sent off the letters.

He said that the next evening, he returned to the burial site, but when he tried speaking to Passal, received no answer. He could think of nothing better to do after that than just go off to his home, no doubt to meditate on the strangeness of life.

As supremely weird as Boulogne's story was, he was able to convince the police that it was nothing less than the truth. Instead of facing a murder trial, Boulogne was charged merely with "Homicide by imprudence and concealment of a body"--the French equivalent of manslaughter. He received three months in prison. Felix Bachelet, another friend of Passal's who had assisted in the scheme, was fined 100 francs.

Passal's remarkable methods of drumming up publicity did indeed have its effect--albeit not quite in the way he had intended. After the whole story came out, there was a great public clamor to read the late author's manuscript. If this was how he scripted real life, so the reasoning went, what must he have put in his book? Newspapers began fighting with each other over the serial rights.

Alas, it all came to nothing. Evidently, Passal had been so involved in his book's publicity that he neglected the book itself. All that was found of his promised "Memoirs" were a few fragmentary notes. Poor Passal could have said, like Oscar Wilde, "I put all my genius into my life."

There was one appropriately ghoulish sequel to our little story. In 1930, an "American souvenir hunter" offered police £80 for Passal's now-famous coffin. The last reports I have been able to find stated that the relic was to be sold at public auction, but I cannot say who bought it or where it might be today.

If the coffin still exists, it should be put on permanent display somewhere, as an unforgettable refutation to that old show business motto, "There is no such thing as bad publicity."

Friday, December 25, 2015

Weekend Link Dump

This Christmas Day Link Dump is, of course, sponsored by the Santa Cats.

What the hell was the Ghost of the Silent Pool?

What the hell are the ghost trains?

Who the hell was Peter Bergmann?

Watch out for those Christmas puddings!

Watch out for those Christmas salad dressings!

Watch out for those Christmas dinners!

Watch out for those Christmas ghosts!

Watch out for those Christmas vampires!

Watch out for those Christmas gawgaws!

Watch out for those Christmas celebrations, full stop!

If you've been following my Twitter posts about Victorian children's books, their cookbooks will come as no great surprise.

A Ralph Thoresby Christmas.

A Richard the Lionheart Christmas.

A Napoleon Christmas.

A Georgian Christmas.

A medieval monk Christmas.

An Antarctic Christmas.

A Calcutta Christmas.

A solitary London Christmas.

A Victorian Christmas.

A Victorian Hospital Christmas.

A Broadmoor Christmas.

A World War I Christmas.

If you still want to risk your life with a Christmas pudding, here are some vintage recipes.

A Dorset Christmas ghost story.

The Shelleys and the occult.

Remembering Clara Barton.

The hazards of being an infertile queen.

The "other" humans.

Mistletoe as medicine.

An utterly characteristic Victorian Christmas poem.

The Gypsy of Cherry Street.

Victorian flirtation cards.

A nice example of medieval Karma.

Oh, just some giant insects attacking Victorian London.

The Golden Farmer comes to a bad end. (The sequel is here.)

Another example of why the most wild-eyed dystopian author could not equal North Korea.

"Revolting oven tragedy." "Illustrated Police News." I think you can guess where we're going here.

The world's oldest ham. No, no, not Nicolas Cage.

The Singing Bookbinder.

In case you're looking for a really exciting tourist destination, you can get to Hell via Ohio.

The death of J.M.W. Turner.

The life of an anchorite.

Why you probably wouldn't want your kids reading Hans Christian Anderson's diaries.

The long workhouse life of Mary Hicks.

A pony takes a balloon ride, 1828.

The early 19th century Lake District.

Bye-bye, Boleskine.

And, finally, I hope everyone enjoyed the supernatural truce!

And here is the end of the final Link Dump for 2015. See you on Monday, when we'll look at what was probably the worst book promotion idea ever. In the meantime, I wish you all a merry Christmas--or happy holidays, or whatever good-cheer formula you prefer.

Wednesday, December 23, 2015

Newspaper Clipping(s) of the Day, Christmas Edition

"'Twas the night before Christmas

And all through the blog

Not a creature was stirring

The cats slept like a log.

The post was composed

On the laptop with care

In the hope that Bad Santas

Would soon be there."

Our annual parade of Yuletide mayhem kicks off with this cautionary tale from the "Illustrated Police News (January 1, 1876):

On Monday night last, or, more properly speaking, early on Tuesday morning, very serious consequences resulted from practical joking. A Christmas gathering of happy folks, both young and old, took place at Tatchet House, Derbyshire, the residence of a wealthy gentleman, named Johnson. It would appear that some private theatricals were about to take place in the course of the week, and a Mr. Brounger, who had brought with him all the necessary materials to personate a dragon, dressed himself in his scaley habiliments, after his companions had retired to bed, and sought their bed-room for the purpose of having, what he called, "a lark." Unfortunately he made a mistake in the room, and entered the apartment occupied by one of the maid-servants and Mr. Johnson's children. The effect can be readily imagined. Two of the children were so frightened that for some time their lives were despaired of; and, indeed, it is very questionable if they ever recover from the terrible effects of the sudden fright. The maid-servant herself is seriously unwell in consequence. This incident, it is to be hoped, will act as a warning to hilarious young gentlemen who are fond of practical jokes.

They were a sensitive lot in the days of old. Here is a similar tale from the "Cambridge Press," December 4, 1875:

As Christmas approaches, it may be well to call attention to the terrible consequences which, according to the "Indianapolis Journal," ensued the other day in that city from an hour's amusement in telling ghost stories. A number of young ladies, patients of the Surgical Institute, were assembled in one of the rooms of the establishment, at a late hour in the evening, and whiled away their time by relating to each other stories of apparitions, hobgoblins, ghosts &c. Either intentionally or by accident the gas was suddenly turned off, and, in the climax of a vivid story, one of the young ladies imprudently threw her shawl over the head of a trembling companion seated next to her. There was a little rustle and a short stifled scream. When a light was obtained the melancholy fact was revealed that the poor girl was mad. She has remained so ever since, and very slight hopes are entertained of her recovery. Considerable risk, indeed, attends the reading aloud of the average Christmas ghost story. Strong must be the nerve of any one who can bear unmoved the first few lines of one of these thrilling narratives knowing that he is expected to sit through the remainder. If not stricken with idiocy at the beginning of the tale, he generally becomes more or less stupefied before the climax is reached, and his distressing condition has become patent to all.

You know, there's nothing like receiving a Christmas gift that has a heartfelt message behind it. From "Granite" magazine, February 1, 1899:

Chattanooga, Tenn.--Grimm Brothers, saloon-keepers, received a tombstone as a Christmas gift. The donor was Mrs. A.E. Riordan, a widow. Her husband had been a confirmed drunkard, and, shortly before his death, Mrs. Riordan warned the saloon-keepers if they sold him whiskey she would prosecute them. On the day Riordan died, it was alleged he bought whiskey at the Grimm saloon. Mrs. Riordan entered suit, and obtained a judgment for $2,500, but up to this time has been unable to collect the money. While evading payment of the judgment, the Grimms erected a tombstone over Riordan's grave. The slab was returned by the widow.

Ah, Christmas in Denmark. The "Free-Lance Star," December 12, 1951:

Copenhagen, Denmark, Dec. 12--Police Commissioner B. Hebo, of the town of Esbjerg decreed that Santa Claus will be arrested on sight.

The reason, said Commissioner Hebo, is that criminals hide behind a Santa Claus beard to commit their crimes and he's not going to have any of them in Esbjerg.

Note to self: Avoid spending the holidays in Minnesota. The "Alta California," December 29, 1866:

St. Paul, Minn., December 28th.--On Christmas Day, at New Ulm, three men were playing cards, when one of them, named Spinner, was stabbed so badly that he soon bled to death. The others were arrested by the Sheriff, and while on their way to the magistrate they were handcuffed and rescued by a drunken mob and hanged. While hanging, the bodies received a number of cuts from knives.

Note to self: Avoid spending the holidays in California. The "Los Angeles Herald," December 26, 1898:

Angels Camp, Dec. 27--The Bariciolo mine, three miles from Sheep Ranch, was the scene of a lively gun fight on Sunday night. As a result a man named Nelson is dead and Thomas Martin is seriously wounded and in a precarious condition. The tragedy was the result of a brawl after a Christmas dinner and no arrests have yet been made.

Note to self: Avoid spending the holidays in Alabama. The "Abilene Reporter," December 27, 1907:

Birmingham, Ala., Dec. 26--Dan Bradley, 16 years old son of a widow at Pratt City mining suburb of Birmingham, died this morning as a result of being blown up by dynamite at a Christmas party given at Mike Dugan's house Wednesday night. Bradley carried the piece of dynamite in his coat pocket. Several boys and girls were knocked down and others badly shaken by the explosion, and the house was badly wrecked.

Note to self: Never spend the holidays in Italy. From the "San Francisco Call," December 29, 1903:

Naples, Dec. 28--The people of this city and its environs have been in the habit of exploding fireworks and bombs during the Christmas season. This year, however, the police authorities forbade the use of dynamite.

The people of the village of Resina eluded the vigilance of the authorities and while the people were preparing the bombs the dynamite exploded. The result was that twelve persons were killed and many injured.

Note to self: Never spend the holidays in Kentucky. From the "San Francisco Call," December 26, 1911:

Middlesboro, Ky., Dec. 25--Edward Van Bever, nephew of Chief of Police Van Bever of Little Clear creek, near here, was blown to atoms tonight while discharging dynamite. Van Bever with a party of friends was celebrating Christmas. Thinking that the fuse attached to the stick of dynamite had been extinguished, he walked up to the dadly explosive to relight it. In a second an explosion followed, throwing him high in the air.

Note to self: Just never leave the house until after New Year's. From the "Lancashire Post," December 27, 1893:

A wedding, which was celebrated at Hazleton, in the United States, on Christmas Day, was the cause of some sensational occurrences. Ill-feeling has prevailed for a long time between the Austrians and the Poles in the town, and after the wedding ceremony an attempt was made, it was alleged, by the Austrians to blow up the Polish party by dynamite. The attempt failed, but a riot ensued, in which firearms were freely used on both sides. A dozen were shot, and many more received injuries from other weapons. It is believed that four will die.

It's striking how our ancestors believed that no Christmas festivity was complete without someone getting blown to bits. The "Lewiston Daily Sun," December 20, 1911:

Latrobe, Pa., Dec. 25--Dynamite being prepared for a Christmas celebration in a foreign miners boarding house at at New Derrick, near here, tonight exploded, killing two men and fatally injuring four others, who are dying in the hospital here.

In case you're planning to feature dynamite and firecrackers this holiday season, think again. The "Star-News, [N.C.]" December 27, 1955:

Raleigh--Three boys injured when a quantity of dynamite exploded in a car Christmas Eve, were in "fair" condition today at a hospital here.

The boys planned to use the dynamite in Christmas celebrating in rural Wake and Harnett counties.

State highway patrolmen said some of the dynamite exploded when one of the youths accidentally dropped a lighted firecracker in the back seat of the car with the dynamite.

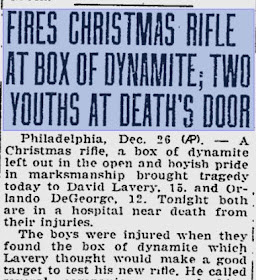

If the Darwin Awards ever opens up a special Dynamite subcategory, these young men would sweep the field. This astonishing headline comes from the "Reading Eagle," December 27, 1925:

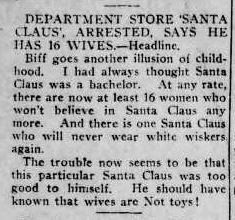

And what's Christmas without a few Bad Santas?

From the "Greenville Advocate," December 7, 1978:

Akron, Ohio--An Akron merchant has complained of being kicked and punched by a man dressed in a Santa Claus suit after he objected to the way the sidewalk Santa was soliciting contributions.

Jonathan I. Kaufman, 30, of the Cleveland Temple of Hare Krishna, is free on $1,000 bond awaiting a pretrial hearing Dec. 15 on an assault charge in the incident.

And then there's the "Palm Beach Post," December 21, 1978. They reported that Santa, otherwise known as 22-year-old Russell Meek, stole a $69 camera from his workplace at the Delray Mall. Meek told police he took the camera because the shopkeeper owed him money.

After his arrest, Meek went back to the mall to try and get his job back, but failed. The arresting officer commented, "I guess they didn't feel like being generous."

Well, this is heartwarming. The "Brandon Sun," December 20, 1923:

Newark, N.J., Dec. 20--Santa Claus was arrested in Newark in the person of Edward Weldon who solicits funds for the Salvation Army in a red suit and white whiskers in the heart of the shopping district. Weldon was arrested in the presence of a group of children on a charge of assault after he had knocked Ernest Goldberg, a crippled sandwich vendor, into the gutter.

Goldberg had moved too close to the Salvation Army "chimney" maintained by Weldon, in hopes of bettering his trade, and a dispute followed.

So, kids, ever wonder where Santa gets the money for all those toys he brings you? The "Melbourne Argus," December 27, 1948:

In Texas, Mrs. Wing Lee's faith in the benign old gentleman was sadly shaken when a badit, disguised as Santa Claus, arrived early in the evening.

When she said, "Haven't you come too early, Santa Claus?" he produced a revolver and robbed her of $10. He then robbed the waiters. Four hundred diners were present.

Santa may have been under the influence at the time of the robbery. The "Canberra Times," December 12, 1959:

New York, Friday--"Santa Claus"--or one of his helpers--was taken to gaol yesterday at Mineola. Police said he was a "bit too full of Christmas 'cheer.'"

Edgar Woods, 69, was still attired in the outfit supplied by a local store when arrested at 2 a.m.

He then was happily directing traffic at a busy intersection. "Santa" Woods was charged with disorderly conduct.

But wait, there's more! The "Mohave Miner," December 19, 1994:

Birmingham, Ala.--A 69-year-old department store Santa Claus has been charged with stealing nearly $100 worth of merchandise from the store where he worked.

Police said Dave Campbell of Homewood, a longtime local radio personality, was released on $500 bond Tuesday following his weekend arrest at the Rich's department store at Brookwood Mall where he worked as a Santa Claus.

Campbell is accused of taking a calligraphy pen set, a Trivial Pursuit game and a back massager, worth a total of about $95.

The parade of sticky-fingered Santas gets even sadder. The "Brainerd Dispatch" for December 20, 1966, reported on another department store Santa who was nabbed for stealing a $1.50 bottle of cologne and a 37 cent bottle of corn and callous remover.

All in all, I'm forced to say that Commissioner Hebo had the right idea.

However, there are aspects to Christmas that are even more frightening, more dangerous than dragons, dynamite, ghost stories, or Santas with corns on their feet. The holiday season has a a dark, sinister figure bringing a message of violence and death to everyone unfortunate enough to be within reach.

No, no, I'm not talking about Krampus. I'm talking about a legendary creature who could have Krampus for lunch.

Ladies and gentlemen, meet Miss Garnet Thompson.

Monday, December 21, 2015

The Murder Chain of Auchindrayne

Because everyone loves quaint, heartwarming slices of family history from the good old days, let me introduce you to John Mure, Laird of Auchindrayne, a man with a memorable formula for handling personal issues.

Mure flourished during the time when King James VI sat uneasily on the throne of Scotland, impatiently waiting for Good Queen Bess to finally die so he could become James I of England. In Mure's district of Carrick, in Ayrshire, the Kennedys held sway. They controlled all local social and political affairs with a good deal more power than the distant, and largely despised, central government of the country. A contemporary history tells of how the current head of the Kennedy clan, Gilbert, Earl of Cassillis, (aka "The King of Carrick,") took a fancy to the rich Abbacy of Glenluce, and determined to get it into his own possession. His method of doing so involved hiring a monk to forge the necessary papers proving Cassillis' rightful ownership of the Abbey. In order to ensure the monk's silence about this unconventional transaction, Cassillis had him murdered. He then saw to it that the murderer kept quiet by having the hired assassin charged with theft, and quickly executed. John Mure, as we shall see, brought this system of evading justice to new heights of glory.

In time, the Kennedys grew bored with fighting rival clans, and took exuberantly to trying to wipe each other out. The main intra-family feud was between Sir Thomas Kennedy of Culzean and the Laird of Barganie. The dispute was ostensibly over the ownership of certain lands, but in truth, Scottish noblemen of those times needed little reason to fall violently out with each other.

Mure had married into Barganie's immediate family, so he decided to strike a blow for his in-law's cause. (He also had a personal grudge against Culzean, who had deprived him of the office of the Bailiary of Carrick.) And, naturally, he meant "strike a blow" quite literally. On New Year's Day 1597, Mure gathered together some of his followers and ambushed Culzean. Unfortunately for Mure but very luckily for Culzean, he launched his attack with more vigor than skill. Mure's prey escaped the melee unscathed.

Well, one can't start new feuds until you end the old ones. Neutral forces managed to patch up a truce of sorts between Mure and Culzean, with this burial of the hatchet cemented by a marriage between Culzean's daughter Helen Kennedy and Mure's eldest son James. All was peace, love, and flowers.

Anyone with even the slightest familiarity with Scottish history can guess how long this lasted. The trouble was reignited when Barganie died and his son, Gilbert Kennedy, took over as head of that branch of the family. Mure convinced the new Laird of Barganie that he, Gilbert, was the rightful head of the Kennedy clan. As a result, the new Laird hatched numerous attempts against Cassillis' life. In December 1601, Cassillis--apparently more angered by some breach of family etiquette of Barganie's than by these murder plots--launched his own surprise attack on Barganie and Mure. This battle left Barganie dead, and Mure severely injured by "ane verie dangeous schot in the theigh." After he recuperated, Mure attempted "daylie ambushes" against Cassillis, but these efforts proved maddeningly ineffective. Frustrated by his failure to kill Cassillis, Mure resolved to gain a consolation prize in the death of Culzean. Peace treaty or not, Mure still held a grudge.

In May 1608, Culzean set out on a business trip to Edinburgh. A "puir schollar" named William Dalrymple was sent to give Mure a message suggesting that Mure meet Culzean along the way near the town of Duppill and let him know if there were any errands he should do in the capital on Mure's behalf.

Now, although Culzean had not taken part in Cassillis' attack on Barganie, Mure suspected he had been privy to this murder. He had long meditated the proper revenge for his relative's death, and saw this as the perfect opportunity. He told Dalrymple to tell Culzean that he, Mure, had not been at home to receive this message. He then let one of Barganie's brothers know where Culzean could be found off his guard and defenseless.

The result of this kindly hint was that Culzean never made it to Edinburgh alive.

Culzean's actual murderers were outlawed, but although everyone suspected Mure was behind the killing, they lacked the direct evidence to charge him with the crime. The only thing that could tie Mure to Culzean's death was if William Dalrymple ever decided to talk. Naturally, Mure was anxious to ensure Dalrymple's mouth was shut forever.

Mure kidnapped the young "schollar" and packed him off to fight in the wars then raging in the Netherlands. He saw this as the perfect way to ensure Dalrymple did not make old bones, without the hazard of killing the young man himself.

Alas, Dalrymple proved to be a better--or luckier--soldier than Mure had expected. In September 1607, he returned to Scotland, alive, well, and with blackmail on his mind. Messy though it might be, Mure decided there was nothing for it but to kill the troublesome fellow himself. Mure cagily let Dalrymple believe he was willing to negotiate a cash settlement, and arranged a secret meeting with him on the beach of Girvan. He took with him a couple of his sons, as well as a James Bannatyne. Dalrymple really should not have been surprised when this meeting ended early, with his murder.

Mure and his assistants tried burying the young man in the sands, but the tide was coming in. It proved impossible to dig a body-sized hole without it immediately filling up with seawater. Finally, in exasperation, they simply flung the body into the waves and prayed the currents would carry it to sea where it would disappear forever.

Mure was an enthusiastic murderer, but, again, he proved to have little talent for the job. A week later, Dalrymple's body was washed ashore. It was soon identified, and Mure's known efforts to keep the young man out of the country quickly made him the prime suspect in the death. The corpse "bled" in the presence of Mure's six-year-old granddaughter, which was seen as indisputable proof of his guilt.

Mure's kinsmen saw nothing wrong with slaughtering each other in open hand-to-hand combat, but this cowardly and brutal murder of a defenseless youth disgusted them. It was considered to be bad sport.

Mure decided that the only way to save his reputation as an honorable upstanding citizen was to commit a more socially respectable murder. He and his men attempted to assassinate Hew Kennedy of Garriehorn, an adherent of Cassillis. Although his enemy survived the assault, it was enough to have Mure proclaimed an outlaw. While Mure was on the lam, he let it be known that he was perfectly willing to stand trial for the murder of Dalrymple if he was given a pardon for the attack on Garriehorn.

King James often showed a curious notion of justice, but this was too much even for him. Mure's offer was rejected. Mure was finally caught and hauled to Edinburgh, where he was imprisoned in the Tolbooth.

Once again, Mure and his son decided that the only way to avoid punishment for one murder was to commit a new one. They resolved that John Bannatyne, the only non-Mure witness to Dalrymple's death, just had to go. The Mures hired a man named John Pennycuik to kill Bannatyne. With a commendable talent for thinking ahead, they also enlisted a relative named Quentin Mure of Auchnull to get rid of Pennycuik when that assassin was done with his work. Quentin's eventual fate seemed obvious, but the Mures decided they would just deal with that when the time was right.

However, the Mures were interrupted in their plans for serially eliminating most of Scotland's population when Bannatyne got word of this plot. Sensibly figuring that the law was less dangerous than his former comrades, he went to the authorities and told all. In 1611, he and the two Mures, father and son, were put on trial for murder.

The Mures denied everything, even when put to torture. Considering that Bannatyne's testimony was the only evidence against them, the Mures may well have gotten away with it, if they had not, like so many other murderers, felt compelled to write self-incriminating letters. Old Mure attempted to send his son a note, which was intercepted by the Crown. We do not know exactly what this letter said, but it evidently contained enough damning words to hang the pair a dozen times. Thanks to this fatal correspondence, the Mures were convicted of Dalrymple's murder (the elder Mure was finally convicted of the killing of Culzean, as well.) While awaiting execution, an assortment of Bishops and Ministers were able to bring the Mures to confess their crimes, and show a suitable contrition. We are told the pair wound up being anxious to go to the gallows, in order to savor the "eternal joys" they were certain awaited them. Bannatyne was rewarded for his role of super-grass with the King's pardon.

Of course, anyone with a sense of justice and humanity is relieved that the Mures were finally stopped in their deadly tracks. However, a blogger with a taste for The Weird must also feel a slight twinge of regret that we will never know just how far the famous "murder chain of Auchindrayne" would have extended if the family had been given free rein.

[Note: Anyone wishing to read a fictionalized retelling of Auchindrayne's many misdeeds may wish to consult Sir Walter Scott's verse play "The Ayrshire Tragedy." It does not, however, really do justice to his illustrious subject.]

Friday, December 18, 2015

Weekend Link Dump

This week's Link Dump is sponsored by the team of Playful Medieval Cats.

(via @LauraEAydelotte)

What the hell was the sea monster of Hook Island?

Where the hell is the world's priciest Christmas card?

Where the hell is Suleiman the Magnificent buried? Now we know?

How the hell did Thelma Todd die?

Watch out for Lake Lanier!

Watch out for those coughing ghosts!

Watch out for those bodysnatchers!

Watch out for those Victorian cosmetics!

Napoleon's last home.

Remembering Gallipoli.

Skating with the Devil.

If you've been wondering what to buy me for Christmas, this would be very welcome.

Rewriting the history of the Mona Lisa.

When the Orkneys were the center of the world.

The alchemy of madness.

Yes, copyright law is getting increasingly insane.

One really freaking old tree.

One of those records no one wants to break: the longest prison sentences.

The making of 18th century shoes.

Color photos of Paris a century ago.

The world's oldest game of tic-tac-toe?

The Myriorama: a sort of early 19th century version of those View-Masters I remember from when I was a kid.

"Knock knock!"

"Who's there?"

Damned if we know.

Archaeologists are busy fighting over Stonehenge.

A canon's murderous servant meets a horrible end.

Who coined the term "Manifest Destiny?"

A Christmas gift guide for all the Victorians on your list.

The horrors of Victorian surgery.

The saga of an 18th century murder.

The Panopticon Prison.

The librarian who classified folklore.

The fear of premature burial.

Victorian hair care.

Well. This was an...interesting moment in medical history.

The official charges against Louis XVI.

This week in Russian Weird: Zombie Putin!

Ravens enjoying the snow.

Raven Bath

WATCH: Ever seen a raven take a snow bath? It's the holiday season, and even Yellowknife's ravens are enjoying the winter wonderland.

Posted by CBC North on Monday, December 7, 2015

And, finally, my favorite story of the week: This Crazy Cat Man is my new hero.

There you have it, gang. Happy link-clicking. I'll see you on Monday, when we'll be getting a lesson in Scottish Family Values. In the meantime, here's The Seekers.

Wednesday, December 16, 2015

Newspaper Clipping of the Day

|

| New Hall of Lincoln's Inn, 1840s |

This somewhat unusual London "ghost" story--let's call it a miniaturized version of "The Devil's Footprints"--appeared in the "Daily Mail" for May 16, 1901:

It is very easy to laugh at a ghost story. Here is one which, laughable or not, actually happened on the night between Saturday, 11th May, and Sunday, 12th May, in a house in a square in one of the inns within a stone's throw of the Law Courts.

A personal explanation is inevitable in a thing of this sort. I will make it as short as possible. I am not a believer in ghosts--neither am I a disbeliever. I am no spiritualist, nor am I a sceptic. I simply don't know; but I am curious.

A rather well known man of letters, a personal friend took chambers about eighteen months ago in the said inn, of which he is not a member. It was an old house--early Georgian, probably--and consisted mainly of sets of lawyers' chambers. His rooms, three sitting rooms and a bedroom, were the only rooms in the building inhabited at night, save for the caretaker, who lived in the basement. The writing man's rooms were on the third floor, and shut off from the rest of the house by a short staircase and a solid door.

He paid an unusually low rent, and explained this by admitting that there must be something queer about the rooms, as there had been seven or eight tenants in two years. They had one and all left in a hurry, and the agents were anxious to let at almost any rent.

My friend filled up most of the wall space with books; read, wrote, and mused during most of the day and part of the night, and admitted in his more confidential moments that "things happened." He did not specify exactly what occurred, but after a time he became nervous and fidgety. Last month he left the chambers rather suddenly, declaring "he could stand it no longer." He cleared away all his belongings, and once more the rooms were empty.

With another friend who is of much the same temperament as myself I arranged an all-night sitting in these rooms where "things happened." Two chairs and a table were absolutely the only furniture left in the place.

We unlocked the front door a little before midnight, locked it behind us, and turned on the electric light. We were alone in the house.

After mounting the stairs from the outer door, there was a smallish room, through which we passed into the principal apartment. This had a fireplace in the north wall and two doors in the south wall, through one of which was the entrance from the stairs. The other door was that of another small room, which had no other means of communication, so that there was no connection between the two small rooms save through the large room.

We searched the place thoroughly, closed and locked the windows, and pulled down the registers of the three fireplaces. There were no cupboards or recesses, no dark corners, and no sliding panels. Even a black beetle could not have escaped unobserved. The walls were entirely naked. There were no blinds or curtains.

On the floor of the two smaller rooms we spread powdered chalk, such as is used for polishing dancing floors. This was to trace anybody or anything that might come or go. We had been warned that nothing happened in a room in which folks were watching.

The doors leading to the little rooms were closed, and we sat in the big room and waited. We were both very wideawake, entirely calm, self-possessed, and sober; expectant and receptive, but in no way excited or nervous.

It was then about a quarter past midnight. We talked in ordinary tones, told each other tales, exchanged experiences--and, curiously enough, discovered we had a mutual friend whom we had never mentioned before, although we had known each other for years.

I only mention these trivialities in order to imply that so far as I am able to judge we were in quite an ordinary frame of mind. We did not deem it necessary to feel each other's pulses or take one another's temperatures, but I am convinced that had we done so we should have found ourselves to be entirely normal.

At seventeen minutes to one the door opposite to us on the right, leading to the little room to which there was no communication save through the room in which we were sitting, unlatched itself and opened slowly to its full width. The electric light was on in all the rooms. The click of the turning of the door handle was very audible. We waited expectantly--nothing happened. At four minutes to one precisely the same thing occurred to the door on the left. Both doors were now standing wide open.

We had been silent for a few seconds watching the doors. Then we spoke. "This is unusual," said I. "Yes," said the other man; "let's see if there's any resistance."

We both rose, crossed the room, and, expecting something, found nothing. The doors closed in the usual way, without resistance. "Draught, of course," was our comment ; and we sat down again. But we knew there was no possibility of draught, because everything was tightly shut. While the two doors had stood open we had both noticed that there was no mark on the sprinkled chalk.

We talked again, but there was a tension, a restraint, which we had not felt before. I cannot explain it, but it was there. A long silence ensued, but I am sure we were both wide awake. At 1:32 (my watch was on the table with a pencil and slip of paper on which I noted the times) the right-hand door opened again, exactly as before. The latch clicked, the brass handle turned, and slowly the door swung back to its full width. There was no jar or recoil when it became fully open. The opening process lasted about eleven seconds. At 1:37 the left-hand door opened as before, and both doors stood wide.

We did not rise, but looked on and waited. At 1:40 both doors closed simultaneously of their own accord, swinging slowly and gently to within 8 inches of the lock, when they slammed with a jar, and both latches clicked loudly, the one a fraction of a second later than the other.

Between 1:45 and 1:55 this happened twice again, but the opening and closing were in no case simultaneous. There were thus four unaided openings and three closings. The first time we had closed them ourselves.

The last openings took place at 2:07 and 2:09, and we both noticed marks on the chalk in the two little rooms. We sprang upland went to the doorways. The marks were clearly defined bird's footprints, in the middle of the floor; three in the left-hand room (the passage room) and five in the right-hand room. The marks were identical, and exactly 2 3/4 in. in size. We are neither of us ornithologists, but we compared them to the footprints of a bird about the size of a turkey. There were three toes and a short spur behind. The footprints converged diagonally towards the doors to the big room; and each one was clearly and sharply defined, with no blurring of outline or drag of any sort.

This broke up our sitting. We raised our voices to normal pitch; measured the footprints, made a sketch of them, lighted our pipes, and sat down in the big room.

Nothing more happened. The doors remained open and the footprints clearly visible. It was just 2:30. We waited till 3:30, discussing things we understood nothing about. Then we went home, locking the outer door behind us, and dropping the key, in an envelope, into the letter box of the house agent's office near by. On the Embankment we were greeted by an exquisite opal and mother-o'-pearl sunrise.

I have stated here exactly what happened, in a bald, matter-of-fact narrative. I am not convinced, nor converted, nor, contentious. I have simply recorded facts. And the curious thing about it is that my curiosity has not been cured.

It eventually emerged that the author of this story was Ralph Blumenfeld, News Editor for the "Daily News." His companion was Max Pemberton, another prominent journalist. Years later, when Blumenfeld was asked about the tale, he insisted that he had described their strange experience quite truthfully, "but don't ask me for an explanation."

Blumenfeld went on to say that the house--which stood in Lincoln's Inn--had been demolished after WWI, and that nothing paranormal had been reported in the building that went up in its place. The Turkey Ghost of Lincoln's Inn is fated to remain an enigma.

Monday, December 14, 2015

The Great Expectations of Thérèse Humbert

In the early 1870s, a family named

Aurignac lived in Bauzelles, a small French village. It consisted of

a widower, who lived with his four children, Thérèse, Marie,

Romain, and Emile. The daughters did the housework, while the boys

did whatever odd jobs they could find. They could not be called

ornaments of their community. The father was a drunkard, who, when

he was in his cups, was fond of boasting of his noble ancestry,

giving himself the fanciful name of "Count d'Aurignac."

These claims were founded on nothing more than his wine bottle,

but as it was true that the Franco-Prussian war had impoverished many

aristocratic families, he found a surprising number of people who

were willing to believe him. Perhaps he came to believe it himself.

After some years, he kicked his story

up a notch. He proudly showed neighbors an old chest, which he had

elaborately locked and sealed. This, he informed them, was the

repository of his title-deeds to Chateau d'Aurignac, a splendid

estate in Auvergne, as well as other documentation that would enable

his children to inherit a fortune.

His friends were suitably impressed.

Aurignac died in January of 1874.

Naturally, the first thing everyone did was to open this mysterious

chest that held the proof of the dead man's noble background and

fabulous wealth. One can imagine the general sense of disappointment

when they discovered it contained nothing but a brick.

Rather than collecting a fortune, his daughter Thérèse became laundry-maid to the family of Toulouse mayor Gustave Humbert. One thing she did inherit, however, was her father's talent for fantasy. She not only continued the fable of descent from a once-mighty family, she embroidered upon it considerably. She told the Humberts and their friends of a fabulous ancestral home in the Tarn, the Chateau de Marcotte. The last owner of this estate, a wealthy old spinster named Mademoiselle de Marcotte, had made a will leaving the chateau and her entire fortune to Thérèse . She repeated this story so confidently and repeatedly that everyone accepted her tale without question. The Humbert family was suitably awed to have their laundry washed by an heiress. The son of the family, a young law student named Frederic, was so taken with her story that he eloped with the soon-to-be-massively rich servant.

Rather than collecting a fortune, his daughter Thérèse became laundry-maid to the family of Toulouse mayor Gustave Humbert. One thing she did inherit, however, was her father's talent for fantasy. She not only continued the fable of descent from a once-mighty family, she embroidered upon it considerably. She told the Humberts and their friends of a fabulous ancestral home in the Tarn, the Chateau de Marcotte. The last owner of this estate, a wealthy old spinster named Mademoiselle de Marcotte, had made a will leaving the chateau and her entire fortune to Thérèse . She repeated this story so confidently and repeatedly that everyone accepted her tale without question. The Humbert family was suitably awed to have their laundry washed by an heiress. The son of the family, a young law student named Frederic, was so taken with her story that he eloped with the soon-to-be-massively rich servant.

Frederic passed his bar examinations,

and for several years he and his wife led a quiet and nondescript

existence in Paris. Every now and then the lawyer would ask Thérèse

about when she'd be getting the de Marcotte fortune, but she always

managed to put him off with various cleverly evasive stories. In the

meantime, she spread the word around all the local shopkeepers about

her "great expectations," which enabled the couple to live

very well on credit.

|

| Therese Humbert with her husband and daughter. |

For a while, at least. Inevitably,

their creditors began to wonder about this grand Chateau de Marcotte.

No one they knew of seemed to have even heard of the place. Matters

finally came to a head when one tradesman owed money by the Humberts

went on vacation near the Tarn. He returned home with the news that

no such estate existed anywhere in the area.

Whoops.

The shopkeepers owed money by the

Humberts did not take this news well. Threats of criminal

prosecution began to fill the air. Thérèse had no choice but to

admit to her husband that her whole story was one big fabrication.

Frederic, whose salary was not nearly sufficient to pay

back all they owed, went to his father--who was by now the Minister

of Justice--and told him the whole embarrassing truth. The senior

Humbert, anxious to avoid an even more embarrassing public scandal,

quietly paid all the couple's debts.

One would think that this narrow escape

would have taught Thérèse a lesson, but it only planted still more

ambitious dreams in her head. Quietly, secretly, this obscure

suburban matron began to build one of the most astoundingly audacious

plans in the entire history of swindling.

In early 1881, a remarkable story began

circulating in Parisian society. People learned that the

daughter-in-law of Justice Minister Gustave Humbert had an amazingly

lucky experience. It seems that while traveling on the Ceinture

Railway some time back, Thérèse Humbert had heard a man in an

adjoining compartment groaning in agony. When she went to

investigate, she found an elderly American man who had suddenly been

taken very ill. He had had a heart attack. She gave him smelling

salts and did what she could to make him comfortable. He recovered

sufficiently to be able to leave the train at the next stop, but not

before he got her name and address. He thanked her profusely for her

kindness, and swore he would never forget it.

The gentleman was a Chicago resident

named Robert Henry Crawford. After they parted at the train station,

Thérèse forgot the whole incident until two years later, when she

received a letter from a New York law firm, informing her that Mr.

Crawford had died and left her four million pounds. She even had

Crawford's death certificate and a copy of this will to prove it.

According to the latter document, Crawford's fortune was to be

divided between Thérèse 's younger sister Marie and the dead man's

nephews, Robert and Henry Crawford. These three legatees were to pay

Thérèse £14,000 a year. These American lawyers wrote that old

Robert Henry had instructed that the fortune should remain in the

Crawford family. Thérèse was to keep the four million pounds in a

safe. Then, when her sister Marie came of age, one of the Crawford

nephews would marry the girl, thus keeping the estate undivided.

After her previous escapade, one would

think that her husband and in-laws would treat this story with a

certain skepticism, but no. The most peculiar feature about the

whole strange story is that the Humberts appear to have accepted

everything she said, and they eagerly told everyone that their

relative-by-marriage would soon be an exceedingly rich woman.

No one in Paris dreamed that the

powerful Minister of Justice could possibly be mistaken, so Thérèse's story went unquestioned. Almost instantly, she became the most

famous woman in the city, and she lost no time capitalizing on her

new renown as a romantic heiress. She rented a grand mansion in the

heart of Paris, featuring, in the downstairs parlor, a large

safe--the safe, which was holding the famed

Crawford millions, as well as an equally lavish country home. She

became the star of Paris society. Her receptions were the hottest

tickets in town. She awed everyone with the splendor of her dresses

and the dazzling quantities of her jewels--all bought on credit, of

course. The ex-washerwoman was living like a queen. France's

wealthiest financiers and business men were willing--eager, even--to

lend huge sums of money simply on the promise that one day she would

come into a fortune, and would then repay these sums at a hefty

interest rate. If anyone showed any signs of failing to completely

believe her story, she would take them aside and "secretly"

show them a bundle of letters, all supposedly written by the

Crawfords. This was enough to remove all doubts.

Thérèse's reign went on merrily for

two years. Then, a French newspaper published an article that, for

the first time, raised a few doubts about her veracity. The man who

wrote the article was from Thérèse's hometown. He remembered well

old Aurignac, his fables about nobility, his safe, and his brick. He

was speculating that history was repeating itself.

Thérèse knew that if these doubts

began to spread, she would be lost. She decided to go on offense,

backing up her lies with still more lies. She began by inventing a

quarrel with the mythical Crawford nephews over where their family

fortune should be kept. The Crawfords, she said, wanted the four

million transferred to a bank for safer keeping, and she objected to

the plan. The bickering between Thérèse and her imaginary

friends--I kid you not--went to court. Lawsuits began to be filed,

some of them originating from the Crawfords, some from Thérèse,

with both sides hiring some of the most expensive lawyers in the

land. The lawsuits on various petty squabbles relating to the estate

went on for years.

This flurry of legal action erased any

questions anyone might have had about the genuineness of the Crawford

fortune. After all, nonexistent people couldn't possibly file

lawsuits!

By this time, Thérèse's sister Marie

Aurignac had graduated from school. The girl, in all innocence,

genuinely believed she was destined to marry "Henry Crawford."

She happily boasted to all her friends about the handsome, charming,

wealthy young American who would some day soon be her husband.

|

| Therese's sister |

All went well until one of Thérèse's

creditors, a banker named Delatte, began to grow impatient for Madame

to open her now-famous safe and start paying back the huge sums she

owed. The longer he had to wait, the more he found himself

suspecting that there was something fishy going on. One day, with an

air of innocent curiosity, he asked Thérèse where Henry Crawford

lived. She told him he was in Somerville, a wealthy suburb of

Boston.

Believe it or not, Monsieur Delatte was

the first person not to take Thérèse's word for this. He took the

first available boat for America to see this mysterious heir for

himself. When he arrived in Boston, he found no sign that anyone

named "Henry Crawford" lived in Somerville, or anywhere

else in the city for that matter. He hired private detectives, and

they also came up empty. There was no evidence that such a person

existed anywhere in the entire country. He angrily wrote a friend

back in Paris of what he had learned. Delatte declared that he was

on his way back to France, where he would expose Thérèse Humbert's

entire swindle.

He never got the chance. Before he

could sail from New York, his body was found in the East River. Was

his death an accident? Suicide? Or a sign that Madame Humbert had

decided to up her criminal game considerably? No one ever knew for

certain.

More and more of Thérèse's creditors

became more and more anxious for their money. Surely, they said with

increasing insistence, it was time for her sister to marry Henry

Crawford and finally open the safe containing the Crawford millions?

Thérèse, in typical fashion, sought to extricate herself from the

old swindle by perpetrating a new one. She launched a plan from

obtaining more money from the public that she could use to pay off

her old creditors. And so the Rente Viagere was born.

In the heart of Paris' business

district, she opened a suite of impressively luxurious office

buildings. It was, the world was told, a large insurance company

that promised to provide annuities. French men and women were

invited to "invest" their money with the promise of

astonishingly large returns. This proved even more profitable than

Thérèse's previous hoax. The prospectus she and her brothers drew

up was so enticing that people all over the country turned handed her

bogus company all they possessed in order to buy annuities or insure

their lives, thinking they were making a can't-miss investment that

would guarantee them a fabulous return on their money. Millions of

francs came pouring into this utterly nonexistent company. Thérèse's creditors were given just enough of this money to keep them

soothed and happy.

For a while, at least. Then,

inevitably, everyone again became impatient for the Great Safe

Opening. Surely, it was long past time for Sister Marie--who had now

become popularly known as "the eternal fiancee"--to marry

her American and haul out the family fortune? Early in 1901, a group

of Thérèse's creditors who were by now, thanks to her, facing

bankruptcy, held a meeting and compared notes. They came to the grim

conclusion that they had all been swindled. It was noted that even

if her story was true, after all these years of expensive lawsuits,

there couldn't be much of the Crawford fortune left!

These creditors went to one of France's

leading lawyers, Rene Waldeck-Rousseau. The lawyer, who had met

Thérèse in court on a number of occasions, instinctively disliked

her, and was quite willing to believe she was a shameless fraud. He

had known a number of people who had been swindled by her--including

his own son-in-law--so there was a personal motive in his desire to

see "La Grande Thérèse " finally brought to justice. He

conferred with the editor of the newspaper, "Le Matin,"

who agreed to publish a series of articles boldly accusing Madame

Humbert of being a crook.

|

| The most notorious safe in France |

These articles emboldened Thérèse's

creditors to demand that the courts order her to immediately open

that damn safe. Unfortunately for her, the presiding judge agreed

that it was the only way to settle the issue. Although Thérèse

and her lawyers vigorously fought this decision, they were finally

forced to give in. Thérèse turned in the keys to her safe, and

May 9, 1902 was set for the Unveiling.

On May 8, Thérèse and her siblings

quietly vanished.

The next morning, the safe was opened.

All it contained was--in quaint tribute to Dear Old Dad--a brick.

Arrest warrants were immediately issued

for Thérèse and her brothers. (It was obvious to everyone that

poor Marie Aurignac had been as duped as everyone else.) In

September, they were finally tracked down in Spain and hauled back to

Paris.

Thérèse, you will be happy to know,

stayed true to form to the last. She refused to admit any

wrongdoing. Instead, her defense was a tale that had everyone in the

courtroom reeling. She conceded that the wealthy American Crawford

never existed. The man who really left her his fortune, she now

said, was Marshal Bazaine, who was by then infamous for having turned

over the fortress of Metz to the Germans. The four million pounds

had been Germany's payoff to him for his betrayal. Thérèse said

that for some time she had not been aware of the source of this

money. When she did realize it had been an enemy bribe, she felt

that in all conscience she could not keep such tainted money. In a

patriotic fervor, she had burned every last cent of it, which

explained why the safe was now empty.

To the surprise of absolutely no one,

the Aurignacs were all found guilty of fraud. Thérèse was

sentenced to five years, Romain three, and Emile two. Her husband

Frederic was also sent to jail, although there is still some question

about whether he was an accomplice or yet another dupe. After she

served her sentence, it is generally said that Thérèse emigrated to

America, where she died in obscurity in 1918. (Other, unconfirmed

reports state that she remained in France, where she lived a

reclusive existence at least as late as 1930.)

The famous safe was displayed for some

time in a Paris shop, where it attracted large crowds. So, in the

end, it finally provided an honest profit for somebody.