"True!--nervous--very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad? The disease had sharpened my senses--not destroyed--not dulled them. Above all was the sense of hearing acute. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell. How then am I mad? Hearken! and observe how healthily--how calmly, I can tell you the whole story."

~ Edgar Allan Poe, "The Tell-Tale Heart."

Anyone who believes that we live in an age dominated by science and skepticism needs to study the history of Pennsylvania. In the rural areas of the state, a belief in witches, hexes, powerful spirits and the like was common until well into the 20th century--for all I know, it still quietly exists today. Remote farm communities saw superstition and folklore not as quaint relics of a medieval past, but as all-too real presences in their lives. Sometimes, these beliefs took the benign forms of good-luck charms, folk medicine, and positive spirituality. At other times, however, believers found themselves haunted by sincerely-held fears of curses and ghostly persecutions.

On occasion, these fears led these tormented souls to defend themselves through acts of violence, even murder. Probably the most famous example is the case of Nelson Rehmeyer. In 1928, a Central Pennsylvania "witch" named Nellie Noll convinced a young man named John Blymire that Rehmeyer had put a curse on him. Blymire and two friends, John Curry and Wilbert Hess, broke into Rehmeyer's home in order to steal a "spell book" they believed he owned. They were unable to find this book, but when Rehmeyer accosted them, the trio gruesomely killed him, in the hope of lifting this curse. The three youths were eventually convicted of the murder. One of the many oddities of the case is that the killers had never before committed any criminal offense, and after their release from prison went on to lead thoroughly normal, law-abiding lives.

Although the following "hex murder" is now largely forgotten, it was very similar to the Rehmeyer case, and, in some respects, even more bizarre.

Our story opens in 1934, in the Pennsylvania farming village of Ringtown. Life there had only a speaking acquaintance with the 20th century. Scarcely any residents had electricity or modern plumbing, and telephones were nonexistent. Among its residents was a sixty-three year old widow named Susannah "Susan" Mummey. She lived in a primitive farmhouse in the hills just outside of town with her adopted daughter Tovillia.

|

| The Mummey farmhouse |

Back in 1910, Susan had had a premonition. A vision or dream told her that if on July 5 of that year, her husband Henry went to his job at a local powder mill, he would die. Although she begged him to stay home on that day, he laughingly dismissed her fears and went to work as usual.

You guessed it. On that very day, Henry was killed when a workplace accident caused a violent explosion.

The tragic event earned Susan Mummey not sympathy, but fear. The deadly accuracy of her premonition caused her neighbors to think of her as a witch--and, considering what had happened to Henry, possibly a dangerous one. From that time on, Ringtown regarded her with a mixture of awe and deep suspicion.

On the evening of March 17, Susan and Tovillia were living with a boarder named Jacob Rice. Rice was staying there because he had a serious foot injury that Mummey was doctoring. (Like many so-called witches, Mummey had some proficiency in the healing arts.)

Before going to bed, Mummey went to change Rice's bandage. As she bent over his foot, the cottage seemed to suddenly explode. The inhabitants heard a frightening roar, and the living room window shattered. The wind coming through the broken glass extinguished their lamps, leaving the stunned trio in darkness. They heard a second blast, which they now recognized as the sound of a gun. Someone out in that black night was trying to kill them.

They crouched on the floor, terrified by the thought of what might happen next. But there was only silence. After a few minutes had passed, Rice finally worked up the nerve to sit up. He could see nothing, and all he heard was the sound of Tovillia whimpering in fear. He called out Susan's name, but got no response. He managed to light a lamp, which illuminated Mrs. Mummey's motionless body on the floor. He saw at once that she was dead.

The two shaken survivors sat huddled together in the darkness, waiting for the morning light to come. At dawn, Rice set out to find help. Tovillia was too hysterical to make the effort. Despite his injured foot, Rice managed to limp to the home of their nearest neighbor, which was over a mile away. This neighbor drove him into town so they could summon police.

Investigators found that Mummey had been shot once through the chest. In one of the walls they found embedded a hand-made bullet, of the sort that was common in the area.

Although the victim had led a quiet, reclusive life, it soon emerged that there was no shortage of people who might have wished her dead. Mummey was a quarrelsome sort who had feuded with most of her neighbors--something that only exacerbated her sinister occult reputation. She was believed to have turned an "evil eye" on one of her enemies, and "hexed" several others. A great sigh of relief went out over Ringwood when it was learned she was dead. In short, the police were confronted with a plethora of possible suspects.

Soon, however, their focus was centered on one man. Three days after the murder, some local boys told the detective in charge of the case that on the night Mummey was shot, they had seen a car parked on the road leading to the victim's home. No one was in the car, but they immediately recognized it as belonging to a 23-year-old named Albert Shinsky.

Shinsky was a polite, well-behaved, good-natured young man with an exemplary reputation. Everyone who knew him liked him. His family was equally well-respected in the community, and he was fortunate enough to be engaged to Selina Bernstel, a pretty, charming girl who adored him. It would be hard to think of anyone less likely to assassinate a defenseless old woman.

Shinsky's life was happy and uneventful until he reached the age of 17. Then, he gradually changed. The once-energetic boy became increasingly lethargic. He lost the energy to work, or do much of anything else. He became thin and haggard-looking. The young man became a shell of his former self, and no one could explain why. Unable to hold down any job requiring physical or mental exertion, Shinsky earned a meager living as a taxi driver for the local mine workers.

When questioned by the police, Shinsky acknowledged being near the Mummey house at the time of the murder. When asked why he was there, he calmly gave a startling reply: "I went out there to kill Mrs. Mummey."

Things only got weirder from there. Without the slightest hesitation, Shinsky treated the detectives to the strangest motive for murder any of them had ever heard. The young man explained that when he was seventeen, he had been working for a farmer who had gotten into a long, extremely bitter fight with Mrs. Mummey over property boundaries between their respective lands. One day, as Shinsky was walking through the disputed land, he saw Mrs. Mummey standing a short distance away, staring at him. Under her hostile gaze, the youth broke out in a cold sweat. He felt like there were hands gripping his throat.

From that day on, he said, he felt a constant "physical and mental torment" that sapped him of all his strength. Susan Mummey had put a hex on him.

Shinsky emotionally described how he constantly felt invisible hands on his shoulders. Pins were stuck into him. A black cat would come down from the sky and attack him while he slept. He tried going to doctors and priests, but they were of no help. What could they or anyone else do against the power of the Devil? In desperation, he consulted some local witch doctors, who gave him various amulets and spells, but they provided only temporary relief. The cat always came back.

Finally, a "spirit" came to him, explaining that the only way he could be free of the hex was if he killed Susan Mummey. So, on the night of March 17, he borrowed a shotgun, loaded it with a "magic bullet" guaranteed to kill witches, and made his way to the Mummey farm.

Shinsky did not enjoy committing murder, but, he cheerfully explained, it worked! Since Mummey's death, he was "a re-born man." He had no regrets whatsoever for what he had done. Indeed, he radiated a joy and relief that these hardened investigators found uniquely disturbing.

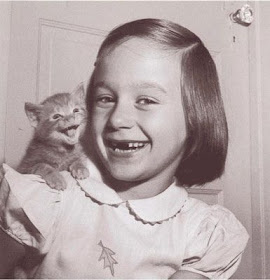

|

| Selina Bernstel |

Selina Bernstel confirmed much of Shinsky's story. She had no doubt that he had been "bewitched." ("My cousin used to be visited by the ghost of an old woman who cast a spell over her.") Her affection for him had a strongly maternal quality. Selina both loved and pitied this haunted young man who would tell her that she "was the only friend he had." She described him as a "little puppy dog" and a "lost soul." The hex, she quietly told the police, had begun to affect her, as well. She would periodically wake up in the morning to see a vision of Shinsky standing at the foot of her bed, his face grimacing in pain. Every time this happened, she'd find out that he had been visited by the evil cat or the spirit-figure of Susan Mummey herself, "leering and leering at him." Selina said that Shinsky had repeatedly begged Mummey to lift the hex from him, but she refused. Selina often asked Shinsky to marry her, but he refused, saying "the witch wouldn't let him."

Although Selina had not known he had committed murder, she admitted that she "knew something had happened, because Albert seemed different and more gay...He acted as if something had been taken off of him." She was too happy with his transformation to ask any questions.

After his arrest, Shinsky became something of a local hero. Other men went to the police alleging that Susan Mummey had cast spells on them, as well--hexes that were only broken with her death. Townsfolk raised a defense fund for him. The murderer himself remained happy and unconcerned. Even the thought of facing the electric chair didn't faze him. "I don't care," he said. "I'm at peace." Selina expressed her willingness to marry him while he still sat in his prison cell, but Shinsky refused any thought of such a dismal wedding. He told reporters he expected to be released soon, after which he looked forward to "marrying my girl."

The court hardly knew what to make of this young man. The story he told was deeply, utterly crazy, but aside from that, Shinsky appeared calm and rational. He indignantly rejected any suggestion of an insanity defense.

Psychiatrists who interviewed him thought otherwise. They came up with a diagnosis of Dementia Praecox, manifesting itself as paranoid delusions, and recommended that he be sent to Fairview State Hospital for the criminally insane. The judge in the case agreed.

Unfortunately for Shinsky, Fairview could give witches and demon cats a run for their money. It had an evil reputation, that, sadly, was entirely justified. It was an unsupervised hellhole where even basic medical care was virtually nonexistent. Guards and staff routinely abused the patients, sometimes to the point of killing them. There were sinister rumors of secret graveyards around the building. It was not a hospital, but an unregulated dumping ground, and would remain so until well into the 1970s. If you were not insane when you entered Fairview, odds were good that you soon would be.

Shinsky disappeared into this living nightmare, never, it seemed, to be heard from again. The world forgot about him until 1968, when a lawyer named William J. Krencewicz learned of the case, which inspired him to lead an effort to have Shinsky reexamined by psychiatrists. Shinsky himself was eager to have his case reopened, even if it meant standing trial for the murder if he was judged to be sane. "I was a stupid, foolish, superstitious young man when I did [the murder], but I do think I've been punished enough."

The issue of what to do with Shinsky dragged through the courts until January 1976, when a judge ruled that he was competent to stand trial. However, the authorities apparently agreed that Shinsky was indeed "punished enough," as I could not find any record that this trial ever took place. Shinsky may well have been released without ever being tried for a murder no one doubted he committed. He went back to Ringtown, where he lived quietly until his death in 1983.

I have found nothing about Tovillia's subsequent life other than the fact that she continued to live in the Ringtown area until her death in 1963. In 1938, Selina Bernstel married a Charles Betterton. She died in Towanda, Pennsylvania, in 2003.

I have long thought that the great tragedy of our species is that--despite our fondness for psychological pigeonholing--our minds and souls are too strange for us to ever understand. How does one categorize Albert Shinsky, an otherwise sane young man who fell into the grip of a belief most people would call utterly insane? Did that make him crazy? Or merely all too human?